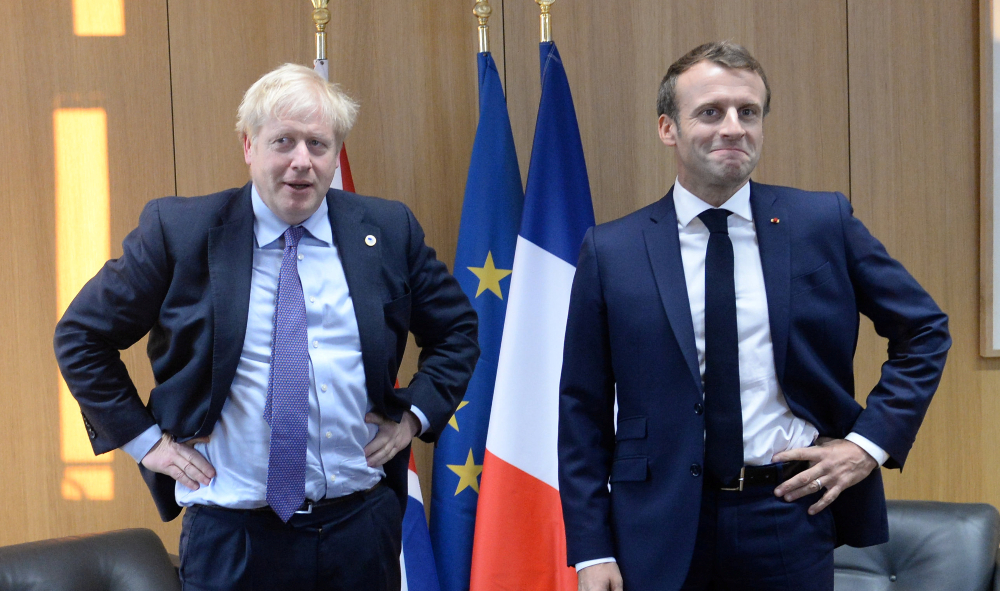

Boris Johnson has traded a hypothetical, temporary, all-United Kingdom backstop for a certain, permanent one for Northern Ireland only. Meanwhile, France is blocking accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania.

With just three hours left before the start of this week’s critical European Council summit, EU and UK negotiators at long last agreed a Brexit deal. It is an arrangement in which Northern Ireland will have a “soft Brexit,” while the rest of the UK will have the hard version.

It is remarkably similar to the arrangement first offered by the EU to Theresa May—having a “backstop” insurance policy in which Northern Ireland remains in a customs union with the EU while the rest of the UK was not. Except it’s no longer a backstop. Unlike the original idea, which would have kicked in only if the UK and EU were unable to reach a free trade agreement allowing an open border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, this new version kicks in no matter what—even if a free trade deal has been agreed.

When the original Northern Ireland-only backstop idea was presented to Theresa May, she refused. She said no British prime minister could contemplate an arrangement which would put a customs border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland, mindful of the fact that she had made herself dependent on the protestant Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) after her disastrous 2017 snap election. She opted instead for a backstop that would cover all of the UK. But this was an arrangement that was unacceptable to the British Parliament, and they rejected her deal.

From Backstop to “Frontstop”

This time, the arrangement is coming with a number of caveats that both Johnson and the EU hope will be enough to get it approved by the British Parliament when it votes on Saturday. The biggest is that the vast majority of the UK will have a clean break from the EU.

On customs, a compromise has been reached in which Northern Ireland will officially be part of the UK’s customs territory, but it will have to follow EU customs rules and will be de facto in the EU zone, meaning a customs border will be placed in the Irish Sea. But because it will still be officially in the UK’s customs area, it can be part of any free trade deals that the UK signs with other countries after Brexit.

The original backstop would have kicked in in 2021, after a two-year transition period, only if the EU and UK had been unable by then to agree a free trade arrangement that would make border checks on the island of Ireland unnecessary.

But the new arrangement would start in 2021 whether or not a free trade deal has been agreed. It can be ended by a majority vote of the Northern Ireland assembly—but that vote can’t take place until 2025 at the earliest, and the exit from the customs union wouldn’t take place for another two years after the vote. Given the dynamics of the assembly, which hasn’t sat in two years, it seems unlikely such a vote to set up a hard border with the rest of the island would ever be taken.

Boris Johnson, who once said a customs border in the Irish Sea would be unacceptable, is now betting that MPs will be willing to accept an arrangement that may be worst for Northern Irish unionists, but better for Leave supporters in the rest of the UK.

Getting It Through Parliament

But Johnson knows this will be a tough pill to swallow for MPs. That’s why he reportedly urged EU leaders last night to explicitly say in their conclusions that they will not grant another Brexit extension. Johnson wants to put the deal to the British Parliament tomorrow saying, “It’s this deal or no deal”.

But MPs believe that if they reject this deal, Johnson will be required by the Benn Act to ask the EU for another extension to give time for a general election or second referendum. The opposition Labour Party may support the deal with the condition that it be put to the people in a referendum, meaning an extension would be required.

The EU did not give in to Johnson’s demand to rule out an extension. They didn’t address the issue in their conclusions, but speaking at a press conference last night, European Council President Donald Tusk seemed to suggest they will grant another extension if the deal fails in London. “Our intention is to work towards ratification,” he said. “Now the ball is in the UK’s court. I have no idea what will be the result on Saturday. But if there is a request for extension, I will consult member states to see how to react.”

Now all eyes are on London to see how MPs react. It is still possible that Johnson will defy the law and not ask for an extension even if the deal is defeated, in which case the EU can’t grant one. In that case, a no-deal Brexit could still be around the corner.

Broken Accession Promises?

After they put the Brexit issue to bed last night, leaders turned to a contentious debate over whether EU accession talks should begin with North Macedonia.

For years, the country’s EU membership bid had been blocked by Greece, which insisted it change its name from just ‘Macedonia’ because it is the same name as a Greek region on its border. This year Skopje complied, and the expectation was that EU accession talks would now begin.

However, France vetoed the opening of those talks last night, in a discussion over the paired accession of North Macedonia and Albania. There is palpable anger with French President Emmanuel Macron at the second day of the summit in Brussels. He says his country is not ready for the start of talks—he was alone in that opinion, but it only takes one country to veto.

Several other leaders shared similar concerns over Albania, and there was hope that he would at least agree to move forward with North Macedonia while delaying the other accession talks, but he wouldn’t budge.

Eastern EU countries are particularly angry with Macron. They say the EU’s credibility is at stake. “We promised them,” grumbled Czech PM Andrej Babiš last night.

Macron Explains His Veto

But Macon says the entire accession process needs reform. The EU can’t keep using membership as a carrot for good behavior. On this point there are plenty who agree with him, and some leaders may be letting Macron take the heat for the North Macedonia decision. The issue came up also in the discussion on Turkey’s incursion into Syria last night, as people call for Turkey’s moribund EU accession process to finally be formally ended.

Many in Brussels say Turkey’s EU accession process is a holdover from when the United States (and the UK) pressured the EU to use the prospect of accession as a carrot for good behavior in neighboring countries—on issues that have nothing to do with the EU. Washington and London wanted Turkey to stay on side with the West, and many believe they pressured Brussels into opening the accession talks in order to string them along.

Now the UK is leaving and the US has lost leverage. The accession charade with Turkey, Ukraine, and others should be ended, many in continental Europe believe.

Even people who think that the five remaining Western Balkan countries (Serbia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Albania, and North Macedonia) should join the EU and then enlargement should end say that, before this can happen, the “Western Balkans and then the EU is complete” plan needs to be made clear.

The leaders will revisit the issue in December.