The German Defense Minister’s proposal for a protection zone in Northeast Syria, voiced just after Turkey and Russia reached an agreement in Sochi that allowed Turkey to invade the north of the country, met with a lot of criticism within Germany and abroad. Indeed, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer left out the details. How did she imagine such a mission playing out?

On top of that, it was too late for the mission: now that Turkey and Russia already have forces on the ground in northeast Syria, the situation has become quite difficult. On the one hand, the Europeans cannot push them out because doing so would require threatening the use of force against Moscow or Ankara. Europe is unlikely to do that. Yet running the mission jointly with Russia or Turkey would only provide a fig leaf of de facto recognition for Turkey’s plan for ethnic cleansing in northern Syria and Russia’s support for Assad’s reign of terror. This needs to be avoided both for moral and political reasons. If the proposal had been in 2018, after Trump expressed his desire to leave Syria and abandon the theater, the proposal would have been more interesting—and perhaps more feasible.

But how practicable is such a proposal really? It is worth digging a bit deeper into what such a mission would have meant for Europe, whether in 2018 or 2019. Could the Union’s member states have replaced the US in Syria as guardian of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)? What would it have meant for European capabilities? The Syrian civil war has raged since 2011. While the refugee crisis in 2015 shook the political landscape in Europe, the war continued another 5 years without the Europeans coming to terms with what to do and how to do it. Although the war now might end with the victory of the Assad regime (and more refugees fleeing repression), Syria is not be the only unstable country in the Middle East and North Africa. Iraqis are protesting en masse. Algeria has to manage a transition of power. Egypt is only stable due to severe repression. Before 2015, the rationale of the German elite was that the traumatic experiences of World War II, in other words the prevailing pacifist and anti-interventionist political environment, would make it easier for Germany to accept one million refugees than to send 1,000 soldiers abroad into a risky combat operation. After the sharp rise of the AfD and the political turmoil the crisis caused in other European states, this rationale may no longer be valid. Thus the “what if” game is a useful exercise to remind us what could be done and what could not.

Shape and Ambition

Before one can determine whether the Europeans could have pulled out such a mission, one needs to think about what would the force have to look like and what the determining parameters would have been. The protection force would have to have multiple aims: to ensure the survival of the SDF and a non-Assad governed Northeast Syria, to deter both Turkey and Russia from an armed incursion, and to provide security assistance to fight Islamic State fighters and other insurgent groups.

The American military footprint in Northeastern Syria was relatively small—1,000 to 2,000 special forces that trained and advised local SDF fighters. However, in order to take over this mission, the Europeans would have had to deploy substantially more forces on the ground to perform the same function. Why? First, because American firepower is outsourced to the US Air Force—which has bases in Kuwait, Turkey (although no strikes are launched from there), United Arab Emirates, and Qatar—and the US Navy, which has a carrier presence in the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. It can call in heavy strategic bombers from overseas bases—an asset Europeans don’t have. And more importantly, it conducts continual (electronic) reconnaissance flights from these bases, using both unmanned and manned aircraft to gain as much situation awareness as possible. Europeans do not have these assets, or only in very limited numbers. They would then have to rely on physical presence on the ground to be aware of new developments and threats, and they need conventional ground-based fire support to make a punch (tanks, artillery). Increased physical presence also means more logistics on the ground, and in a counter-insurgency theater, such logistical movements need to be protected against mines and ambushes, again expanding the number of ground forces needed to do the same job.

What’s more, the United States is an offshore balancer that can draw in sizable forces from beyond the horizon if necessary. Russia would ultimately risk nuclear escalation if it engaged US forces in serious manner. Hence even a very limited number of US troops would be able to deter any Russian-Turkish military incursion into Syria. By their mere presence, they create “no-go” zones for Moscow and Ankara. With European powers, things are not that clear. They might considerably hurt Turkey in the case of confrontation, but not at least because of the refugee issue, Erdogan believes he has as much leverage over the Europeans as they have over him. Russia could out-escalate any conflict with minor nuclear powers in Europe, although it is still be doubtful whether Moscow would really want to risk such an escalation over Syria (probably not). Still, the Europeans would have to field heavy forces, including a sizable number of armored maneuver forces into the theater to successfully deter an armed incursion by one of the neighboring states. This force could not just be the usual peacekeeping force. It would have to be able to stand its ground in major fights, such as those between US Special Forces and Russian-mercenary led Syrian forces in May 2018.

What Would the Mandate Be?

The mandate would have been another issue. Since Russia and China have continuously blocked any UN presence in Syria (including fact-finding missions on chemical weapons), such a mission would have to be carried out without a UN mandate. One way to legitimize a military presence in Syria without an UN mandate would be to recognize the SDF leadership as legitimate government and seek its consent. However, that would probably spark a Turkish full-scale invasion to start with, as preventing exactly this is Erdogan overall war aim. The third option would be to cite Europe’s responsibility to protect, as the extension of the rule of both Assad’s regime or Erdogan’s Turkey over the region would have dramatic consequences for the civilian population. While it is possible to make this, one should not believe that all European member states would follow this line and contribute troops. Even in Germany, where the idea originated, the political establishment would have to fight an uphill battle. And most smaller states would probably decline to send troops under any circumstances (their contributions usually are only symbolic, so in the end it would hardly matter).

Logically, the European force could not deploy and supply itself via the shortest and most convenient route, through Turkey. Doing so would create a logistical Achilles heel and make Europe politically dependent on Ankara—think of how the West has had to go through Pakistan to supply forces in Afghanistan. If Israel and Jordan granted the Europeans the right to fly over their territory (which is likely as neither Tel Aviv nor Amman has much interest in strengthening Assad in Syria) and conduct air operations from Jordan, there would be an air-bridge close to the theater of operation. But the bulk of the mission would need to be deployed and supplied via Iraq. The theater of operations in North-Eastern Syria does not have a large operational airport (Dei es Zur is on the other river-bank). Therefore, due to the lack of transport aircraft, the heavy equipment would have to be shipped to Kuwait via the Suez Channel and then transported via the land route. And those transport ships would have to be leased from the private sector or the US Sealift Command because Europeans do not have capacities on their own.

The Numbers Don’t Add Up

Do the Europeans have enough forces to mount the mission? Well in theory yes, but it would still be tricky. According to the European Defense Agency, EU member states have 405,000 deployable land force soldiers. On paper only of course! Unfortunately, the most recent data set compiled by the EDA does not list the troops per country. The 2013/2014 booklet was the last to cite numbers for each country and hence provides an opportunity to check the numbers.

Overall, 276,395 land forces soldiers were deemed deployable in 2014, but due to reorganization in their armed forces, Italy and Germany at the time did not provide numbers. Both are professional armies, and assuming they would declare the bulk of their land forces deployable, the figure could well end up at 400,000. But that also illustrates how useless this number is, as no country would be willing or able to commit its entire army to one mission. Still, one should also look at the Eastern-Flank armies like Poland, Romania, or Sweden: their number of deployable troops plummeted in 2014, because most—even high readiness troops—got re-assigned to tasks of national deterrence and defense. This is a limited factor that needs to be taken into account: these states will keep the bulk of their forces, and particularly heavy, mechanized forces in their own country and not send them abroad – they simply fear a Russian incursion into their own country more than a Russian incursion into Eastern Syria.

Another, more useful number is that of sustainably deployable land forces. As there needs to be an alternation between training/formation, recreation, and deployment, only a limited number of soldiers can be deployed at the same time. This number should indicate how many forces a country could deploy over longer periods of time in a theater. In 2016, the 94,000 soldiers were earmarked as sustainably deployable. In fact, for many countries (like France, Germany, or the United Kingdom) this number represents the maximum number of personnel they could possibly deploy. During the heyday of Western interventionism in 2008, when most European soldiers were deployed, the EU member states mustered roughly 80,000 deployed soldiers, particularly in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2011, 71,000 soldiers from EU member states were still deployed abroad. But since then, defense budgets have plummeted due to financial difficulties, and in 2014 additional tasks of deterrence, reassurance and national defense against Russia were added. So while the number cited above looks fine on paper, the actual number of deployable troops will be considerably lower.

Again, a look into the 2014 data set provides an overview over the national distributions. Assuming roughly 20 percent of German and Italian forces are sustainably deployable, adding them would give us approximately the numbers of 2016. Hence one may assume that between 2014 and 2016 (and most likely now), there was very little change as armed forces are quite large bureaucratic apparatuses.

This has to be measured against existing commitments. In 2016, EU member-states had 35,000 soldiers deployed in missions. Existing missions could hardly be abandoned, so any new mission would have to come on top. Again, comparing this to 2014 figures (if the German deployments were added, it would add up to roughly the same number), one can see the heavy commitment of France in particular to missions in Africa. The drawdown of troops in Afghanistan has, though, likely made more UK troops available.

Another problem would be the composition of these forces. Most deployable forces of smaller nations are light infantry units best suited for peacekeeping. They would be rather ornamental contributions in this scenario, without much practical value. Special forces would still be useful to fight ISIS, paratroopers, marines, and other elite-infantry units good at training and advising local SDF fighters. But then there is the issue of who would commit heavy armored forces to deter Russian and Turkish incursions. This would not only be the most expensive deployments; these forces would also face the greatest danger.

Here, only France, Germany, the UK, Italy, and Spain have heavy mechanized forces that are not immediately committed to national defense tasks. But given the dire state of real readiness (in contrast to strength on paper) of the Bundeswehr and the Spanish and Italian armed forces, as well as the already high commitment of French forces, it would to a large extent come down to London’s willingness to commit forces.

When it comes to the air war, the situation is similar. On paper, the EU has enough fighters. But in practice, the air forces of smaller nations are only capable of domestic air-policing. They are not meant to be deployed. Those air-forces who do have the capabilities to fight and be an effective air-support force in Syria already have existing commitments in many overseas territories. And aircraft and their crews need to rotate too.

Lacking Air Power

Nevertheless, judging purely theoretically, on the basis of readiness, roughly 180 tactical fighters (Eurofighters, F-16, Mirage 2000, Rafale, Tornados, F35) could probably be scrambled across the entire continent for an air campaign. Here the availability of airbases would be the most restraining factor. Only France has an aircraft carrier with full strike capability; all other planes would need to be based in Cyprus (extensively air-refueled), Jordan, Iraq, and with air-refueling, in the Gulf. So in fact there would be fewer fighters used, but Europe could provide them.

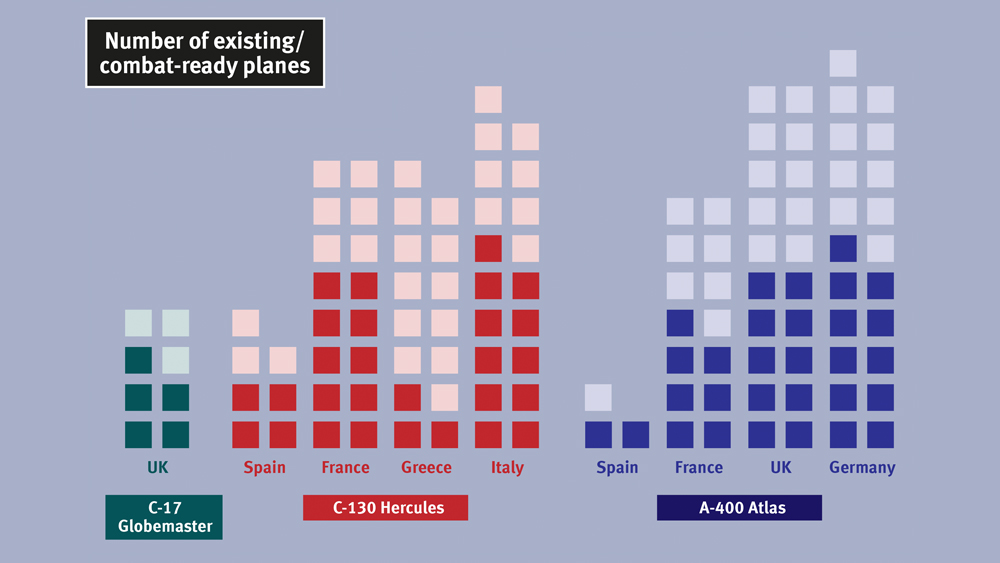

But the status of other key enabling factors is weaker. Only the UK has (a handful of) C-17 Globemaster transport aircraft, which can carry a battle tank. With 50 percent readiness assumed for the A-400, 57 of them could transport other armored vehicles. The various C-130s have a lower payload and would only be suitable for light vehicles and follow-on supplies. Hence the bulk of the force would have to deploy by ship. This would take time and would give Russia and Turkey the opportunity to preempt such a mission.

Air refueling is an even bigger bottleneck. Assuming that heavy-loaded transports and fighters from distant bases need mid-air-refueling to transit to the theatre of operations, and assuming 60% readiness for its tankers, Europe could muster 15 A-330 MRTTs, and 2 KC-767s, and if France’s deterrence forces can spare it, then a single KC-135. Most of these aircraft would be British. Europe is even more reliant on London in terms of electronic reconnaissance aircraft and drones, where the UK either has unique capabilities or French counterparts are already committed. Still, even if London did weight in, it could only muster a tiny fraction of what the United States currently fields in the Middle East.

Now while this is just an approximation based on available data (EDA defense data and the IISS Military Balance 2019), the exercise is worth doing just to remind Europeans how precarious the situation regarding power projection and deployment is. Europe’s shortfalls on intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, air-transport, mid-air refueling, drones, etc. have been known for decades. But grand speeches about European strategic autonomy, a European Defense Identity, and a Defense Cooperation do not provide these assets—only hard money in procurement budgets does. Given the continuous unrest in the Middle East, the unreliability of the commander in chief in the White House, and the specter of Brexit, one should look twice at this theoretical game-play and ask oneself whether Europe can still afford to just muddle through in defense matters.