Still, for all the concern, some of the countries with the largest – and older – immigrant communities have yet to see any immediate political effects. In the United Kingdom, where attention is currently focused on immigration in general rather than refugees in particular, the staunchly anti-immigrant UKIP seems to be driving voters away by focusing on the issue. Meanwhile, in France, Front National continues to grow in size and clout – but no faster now than at any other point since Marine Le Pen took over party leadership in 2011.

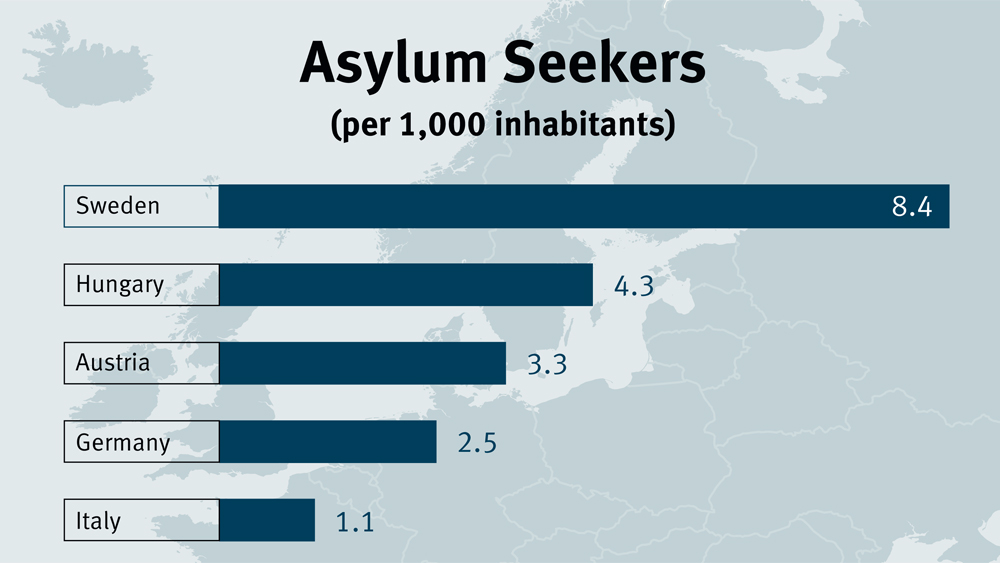

That said, there have been sharp shifts in the domestic politics of the countries hit hardest by the recent tide of refugees. And it is no longer the border countries that are most affected; though Greece and Italy have often been points of ingress, they have generally not been their final destination. Instead, Sweden, Hungary, Austria, Malta, Denmark, and Germany have taken the lion’s share of the refugees proportional to their populations, with Sweden currently hosting 8.4 asylum applicants per 1,000 people (compared to 1 in France and .5 in the UK).

The political effects in Sweden have been immediate. According to a poll carried out by YouGov in August, the Sweden Democrats, an anti-immigrant party with neo-Nazi roots, is now the largest party in Sweden with 25.2 percent of the vote. This represents a dramatic increase from their fortunes just a few years ago: in 2010 the Sweden Democrats entered parliament with only 5.7 percent of the popular vote, while their support was only 12.9 percent last year. The party’s head, Jimmie Åkesson, described the 2014 election as “a choice between mass immigration and welfare.”

Meanwhile, in Hungary, the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been using increasingly aggressive rhetoric when discussing the refugees passing through the country’s borders, saying on September 3 that the influx of refugees threatened Europe’s “Christian roots”. The country has been erecting a barbed wire fence on its border with Serbia to deter migrants from entering from the South.

Germans have been among the most willing to take in more refugees. A poll conducted by ARD DeutschlandTrend between August 31 and September 2 showed that 37 percent of Germans think that the number of refugees the country is currently taking in is appropriate, while 22 percent believe Germany could accept even more; only 33 percent said that Germany should take in fewer refugees. An overwhelming majority – 88 percent – would be willing to personally donate money for the wellbeing of refugees, while 67 percent said they would be willing to volunteer to help, numbers supported by visible demonstrations of support in Frankfurt and Munich for refugees arriving from Hungary.

But there is also a visible backlash. Over 200 attacks against refugee shelters have been committed in 2015 so far. While Germany does not have a populist anti-immigration party with national reach, a high number of the attacks have been perpetrated in regions (notably Saxony) where the Dresden-centered anti-immigrant PEGIDA movement (short for “Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes”, or “Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the Occident”) or the neo-Nazi NPD party have footholds.

Germans themselves are particularly concerned about the rise of right-wing attacks. A YouGov poll conducted in August found that 68 percent of Germans believe that there are more crimes connected to the extreme right-wing than ten years ago, and 57 percent said that they wanted more money invested in combating right-wing extremism.

Read more article in the Berlin Policy Journal App – September/October 2015 issue.