In Italy’s election campaign, political confrontation has given way to a mudslinging contest. Beppe Grillo, the founder of the populist Five Star Movement, has certainly contributed.

Italy has found itself in the middle of a vicious election campaign leading up to the March 4 vote. It is more of an election war, really, fought with lies, propaganda, distortion, intolerance, violence, and a torrent of hatred.

A glance at the country’s social media is enough to get a sense that this is not simply a matter of differences of opinion, nor is it about persuading voters. Anyone with a different view is not simply a political opponent―they are an arch enemy, who must be destroyed along with their ideas. In Italy, political confrontation has always oscillated between drama and melodrama. But the punches being swung this time around are increasingly brutal.

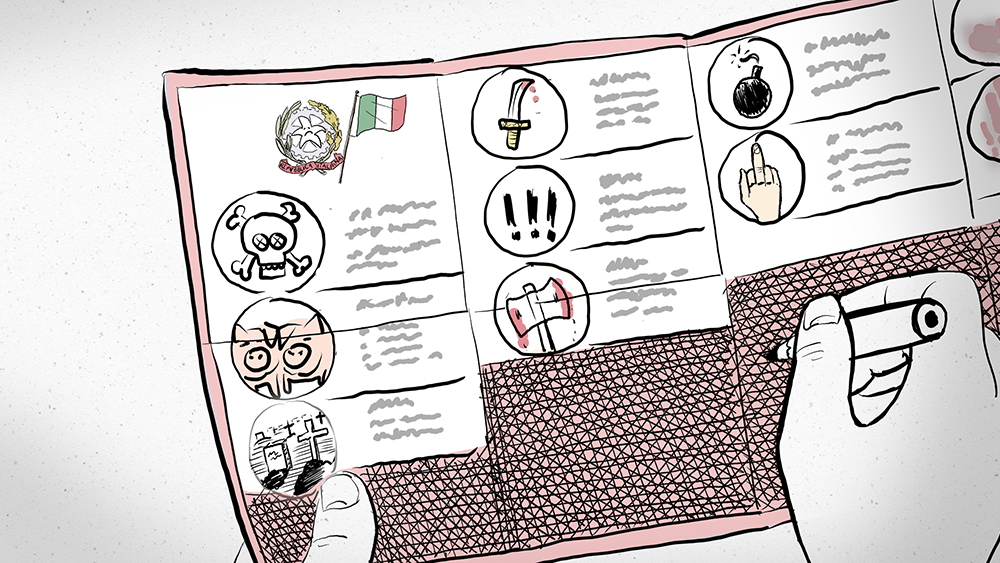

The weekly newspaper L’Espresso produced a catalogue of such insults at the end of last year, gathered under the title “Die, You Bastard.” The collection showed that regular social media users are far from the only ones unscrupulously venting their rage. Politicians and media outlets seem to completely underestimate the potential for violence that comes from these tirades of hate.

For example, just before parliament voted on the controversial new electoral law last year, an MP from the Five Star Movement (M5S) wrote to Ettore Rosato, a Social Democrat who helped draft the bill, saying: “Rosato, let’s make a pact: if the constitutional court approves your law, we’ll burn you alive.” Meanwhile, Vittorio Feltri, editor-in-chief of the daily Libero―allied to the populist Northern League―posted on Facebook: “Dying of malaria is not normal. The infection is coming from far away, from black Africa. Stop the intake!”

For its part, a far-left movement dug out a photo of former Prime Minister and leader of the Christian Democrat, Aldo Moro, who was kidnapped by Red Brigades militants on March 16, 1978, and found dead a few weeks later in the trunk of a Renault 4. His kidnappers had taken the photo during his captivity and passed it to the Italian media. The public was shocked, and even today the photo is seen as a dramatic testament to a period of trauma.

Yet that didn’t stop the left-wing extremists from swapping Moro’s face for that of Matteo Salvini, leader of the Northern League―complete with a gag over his mouth. The doctored image was captioned: “I have a dream.” The next day, the Rome-based daily Il Tempo published a similar picture, this time with the image of lower house speaker Laura Boldrini.

In fact, Boldrini seems to have become the object of the most vile and extreme attacks―because she is a woman, because of her pro-refugee stance, and because she is on the left. One activist for the “Us with Salvini” list responded to an alleged rape by an immigrant by asking: “When will this happen to Boldrini and the women of the Social Democratic party?” This was outdone by an even more alarming post featuring an image of a beheaded Boldrini and the words: “This is the end she had to meet in order to appreciate her friends’ customs.”

Throwing Up the Media

The press, of course, have not been left out, and the former leader of the M5S movement, Beppe Grillo, has been particularly vicious. “I’d like to eat you all up and get so full that I can vomit you straight back out again,” he told the press on one occasion.

Grillo’s aggressive and powerful rhetoric is not the only reason that there seem to be no more taboos when it comes to verbal confrontation. But it is undeniably a factor. In 2005, Grillo wrote a blog post announcing the start of his “Parlamento Pulito” (“Clean Up Parliament”) campaign. It targeted 20 MPs who had retained their seats in parliament despite being convicted of crimes. Grillo bought a whole page in the International Herald Tribune to expose the issue. He attracted a lot of attention from abroad, but far less in Italy itself, starting with the media. So he changed his tactics, and organized the first national “V Day” for September 8, 2007. V stands for the expletive vaffanculo, meaning “fuck off.” This time around, Italians and the country’s media were listening.

Political disputes in Italy have always been something of a gladiator fight. But the current confrontation has flagrantly crossed the boundaries of civility so often that Amnesty International Italy has started the campaign “Count to Ten.” “There’s not an hour that goes by in which social media, or traditional media, aren’t reporting on the latest hate-filled statements, and anyone can be the target, whether migrant, woman, Roma, LGBT person, or a member of a religious minority,” the NGO wrote on its website. The campaign features a barometer measuring the hate level in the run up to the election.

It is hard to say whether this project is really achieving its goal of getting people to dial down their tone. But the threat is certainly real—these hate tirades are followed by actions, as the last few weeks have shown. A few days after an 18-year-old was murdered in the city of Macerata and a group of Nigerians came under suspicion, an Italian man embarked on a shooting spree targeting African immigrants. During a visit by Boldrini to a Milan suburb, the right-wing extremist group Casa Pound publicly burned a straw puppet effigy of the lawmaker. Brenda Barnini, mayor of the Tuscan town of Empoli, was sent an envelope containing two bullets, a swastika, and the message: “You prefer niggers to your own countrymen. We will finish you.”

Hugo von Hofmannsthal once wrote: “Words are not in the power of men; men are in the power of words.” At the moment, Italy seems to be in the power of some particularly nasty ones.