No matter how Canada’s October election goes, Germany’s multilateral agenda is likely to see a transatlantic setback.

After more than a year of discussing and promoting it with foreign counterparts and his own ambassadors, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas “launched” the Alliance for Multilateralism with his French counterpart Jean-Yves Le Drian and others on the sidelines of the 2019 United Nations General Assembly in New York.

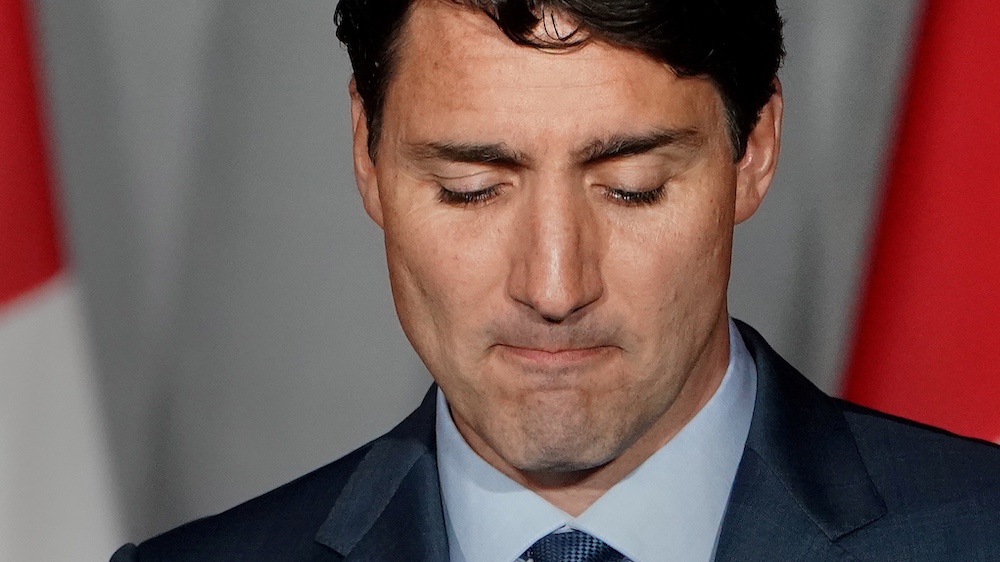

But the fledgling formation already faces one of its first tests this month. One of its core members, Canada, is holding elections—and depending on the outcome, the new government could find it hard to fully commit to the Alliance for Multilateralism. Even if Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, whose government supports the alliance, wins re-election on October 21, his global influence will likely be reduced. Multiple scandals have tarnished both his domestic brand and global celebrity.

Meanwhile his main opponent, the Conservative’s leader Andrew Scheer, comes from a party with a history of skepticism toward the UN and EU—the very institutions that the Alliance for Multilateralism’s French and German leaders view as integral to their own foreign policy interests.

France and Germany have never explicitly confirmed that the alliance is a direct response to the nationalism that culminated in the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the EU or Donald Trump’s election as US President, but its intent is implicit. This has prompted partners with historically close ties to the United States, such as Australia, to wonder where Trump’s America fits into the alliance’s goals and initiatives. Although Canada and the US boast one of the closest bilateral trade relationships in the world, the Trudeau government has not hesitated to support the alliance as one of its core members.

In fact, during Trudeau’s premiership, the world’s tenth largest economy has generally gone the opposite way of its increasingly isolationist Anglo-Saxon partners. Trudeau’s Liberal Party has emphasized completing the CETA free trade agreement with the EU, increased the country’s intake of refugees from Syria, and pledged a major climate package ahead of signing the Paris Agreement. Whether it’s talk of a liberal alliance with Emmanuel Macron, a joint appearance at Montreal Pride with Ireland’s Leo Varadkar, or an unexpected friendship with Germany’s Christian Democrat Chancellor Angela Merkel, Trudeau has been a close partner to many European leaders. They, in turn, have been keen to pose with Canada’s young prime minister in hopes of benefiting from Trudeau’s global star power.

Trudeau’s Sinking Popularity

However, even if Trudeau wins re-election, that star has arguably burned out, making his celebrity less useful to the alliance than it might have been previously. So far this year, he has admitted to wearing blackface makeup on multiple occasions. Parliament’s ethics commissioner rebuked him for improperly pressuring Canada’s attorney general to drop a criminal investigation into a company based in the electorally important province of Quebec. Recent polls have Trudeau’s Liberals and the Conservatives neck-and-neck in the popular vote, yet Canada’s majoritarian electoral system is likely to give the Liberals an edge in parliamentary seats. That said, electoral scenarios in which the Liberals either lose their parliamentary majority or lose power altogether are entirely possible.

Echoing many of their European counterparts, the Trudeau Liberals are of an instinctively multilateral foreign policy culture, though they are still prepared to deploy military assets. For example, Liberal then-Prime Minister Jean Chrétien committed Canada to NATO’s Kosovo and Afghanistan campaigns, even as it opposed the 2003 War in Iraq.

Should Trudeau lose his majority, he may end up having to cooperate with the more force-wary New Democratic Party (NDP). Historically, the NDP withdrew support for NATO’s Kosovo campaign and was, in 2007, the first party to call for Canada to withdraw from Afghanistan. Like Germany, Canada spends around 1.2 to 1.3 percent of GDP on defense (i.e. far less than the agreed NATO aim of 2 percent), and the NDP will be particularly reluctant to support the already hesitant Liberals on any further increases or troop commitments.

So if Trudeau returns to the G7 table, he is likely to do so with less political capital. He may also have difficulties getting smaller parties to support some of his foreign policy initiatives. Yet Canada would likely remain at the core of the Alliance of Multilateralism.

Multilateral Skeptic

Should Scheer become Canada’s next prime minister, he might well pivot away from Macron and Merkel toward Trump and Britain’s Boris Johnson. Skeptical of the EU, Scheer once claimed he was pro-Brexit “before it was cool,” penning an op-ed to urge a Leave vote. The Conservative policy platform pledges to follow Trump’s lead and move the Canadian Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem. Sending a similar signal, Scheer used his first major foreign policy speech to lambast Trudeau’s Liberals for repealing Canadian sanctions against Iran—which were part of the 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran which was deemed a success by everyone but the Trump administration.

While Canada’s European partners—including Germany—have spent the last three years standing by the deal, Scheer pointed to Trudeau’s Iran policy as evidence that Canada is drifting away from its closest ally—the US. Scheer has also pledged to pull Canada out of the UN’s global pact on migration at the same time as fellow conservative Angela Merkel continues to argue forcefully in favor of it. On climate, Scheer and his fellow Conservatives originally voted against ratifying the Paris Agreement before later pledging to reaffirm support for the treaty’s targets.

Scheer’s foreign policy arguments reflect a tradition among Canadian Conservatives of prioritizing the Canada-US relationship and being skeptical toward the UN in general. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper advocated for Canada to join the US in Iraq when he was opposition leader and deliberately skipped the opening of the UN General Assembly more than once as Prime Minister, despite being in New York at the same time.

Both Trudeau and Scheer intend to continue campaigning for a Canadian non-permanent Security Council seat in 2021—Canada will have to beat out either Norway or Ireland to get one. As Germany and France decide which two countries to support, they will be asking questions about what sort of partnership to expect from a Conservative Canadian government. Would it remain committed to the Alliance of Multilateralism as a core member? Would it back other priorities in the areas of trade, climate, or security? Canada may be not as geopolitically influential as its larger Anglo-Saxon partners, but with Trump and Johnson already sitting at the G7 table, the answer is more important than one might think.