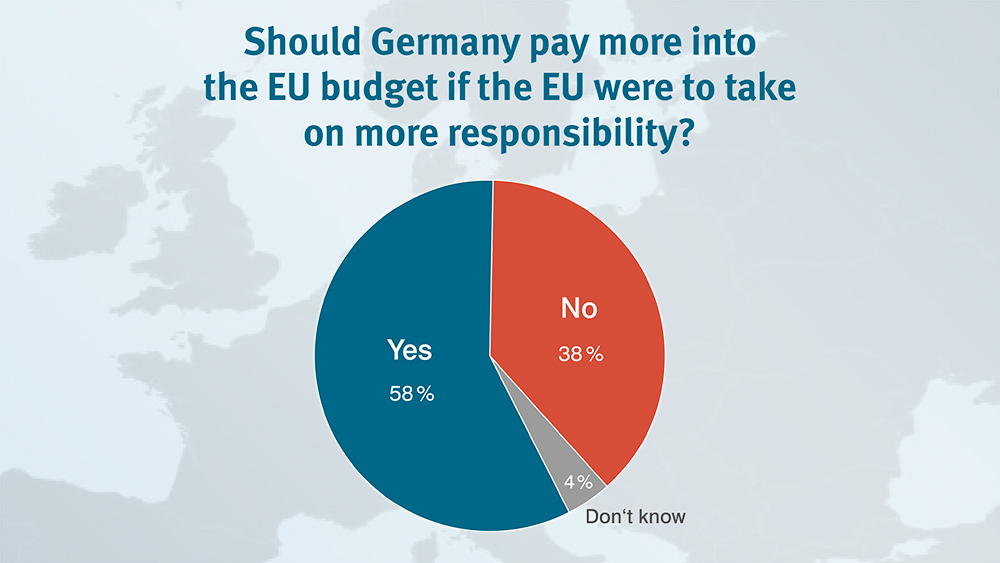

At first glance, the results of a recent Forsa poll for our sister publication Internationale Politik may seem puzzling. The survey asked Germans whether they agreed with the following statement: “Germany should pay more into the EU budget if the EU were to take on more responsibility in certain areas.” After being told for years that they were indulging profligate southern European countries—and in the aftermath of an election that saw significant gains for the euroskeptic Alternative für Deutschland (AfD)—one would expect Germans to be leery of promising yet more money to Brussels. And yet, 58 percent of Germans agreed, even accounting for the 77 percent of AfD voters who felt otherwise.

What is behind this strong support for Europe? After all, the question was not asking how Germans felt about the EU, but whether they’d be willing to pay more for it.

The annual Eurobarometer survey initially offers little insight. Compared to fellow member states, Germans were not particularly likely to say they had a positive image of the EU. Forty-five percent said they did, a higher percentage than in France and Greece, but a lower one than in Ireland, Luxembourg, Poland, and Portugal. Less than half of Germans said that they trust in the EU, lower than the corresponding percentages in Belgium, Sweden, the Netherlands, and Portugal, as well as in many of the newer eastern member states.

One clue can be found in how much respondents felt their respective countries influenced EU policy. Here, Germans were more enthusiastic: roughly two-thirds agreed with the statement “My voice counts in the EU,” more than in any other member state except Denmark (in fact, a full ten percentage points more than in every other country but Sweden and Austria). For better or for worse, Germans feel like they have influence over the EU’s journey—and it’s possible that this is making them more amenable to chipping in for gas.

Further, Germans see the EU’s priorities aligned with their own. When asked about the most important issue facing the EU, most respondents EU-wide said immigration (39 percent), followed by terrorism (38 percent). This breakdown was mirrored in individual member states, almost all of which described immigration and terrorism as the EU’s top two priorities (with the exception of Austria, Slovakia, and Sweden, which also emphasized member state finances, crime, and climate change, respectively).

These priorities rarely reflected what respondents saw as the most pressing problems affecting their own nation: the Dutch said their biggest problem was health and social security, Lithuanians said inflation, the Irish and the Luxembourgers both worried about housing scarcity, and many of the crisis-hit countries said unemployment remained their biggest issue. Not so in Germany: pluralities in Germany (40 percent), Belgium (29 percent), and Austria (28 percent) listed immigration as their country’s greatest concern. The average German, in short, sees Germany’s problems as Europe’s problems—and is willing to pay a bit more to have these dealt with in an EU-wide capacity.

What is particularly interesting is the party breakdown of the Forsa results. Voters of the conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and their Bavarian sister Christian Social Union (CSU), together representing the largest bloc in Germany’s governing coalition, were ambivalent: only 56 percent agreed with providing greater funding for the EU. Voters of the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD), junior partner in the coalition, had no such qualms, with just below three-quarters (70 percent) saying the country should increase its contributions. No great surprise given that the SPD’s last candidate for chancellor, Martin Schulz, was a long-serving president of the European Parliament.

But 70 percent of Free Democrats (FDP) said the same, seemingly undermining a fundamental stance of its party chairman, Christian Lindner. The young FDP leader walked out of one of several rounds of coalition talks in a huff, claiming he could not in good faith agree to a coalition agreement that would have Germany contributing more to the European budget. While he characterized his behavior in coalition talks as good-faith negotiating, there was significant speculation that he had been seeking an excuse to walk out from the beginning. Julia Klöckner, one of the CDU’s negotiators, called it “well-planned spontaneity.”

Whatever Linder’s motives, he seems to have misjudged voters. An ARD-DeutschlandTrend poll from December 2017 showed his national popularity dropping by 17 percentage points following his auto-da-fé, and a 10-percentage-point drop within his own party. It seems that even within the FDP, a majority continues to see the EU as an efficient way to share the burden of Germany’s problems.