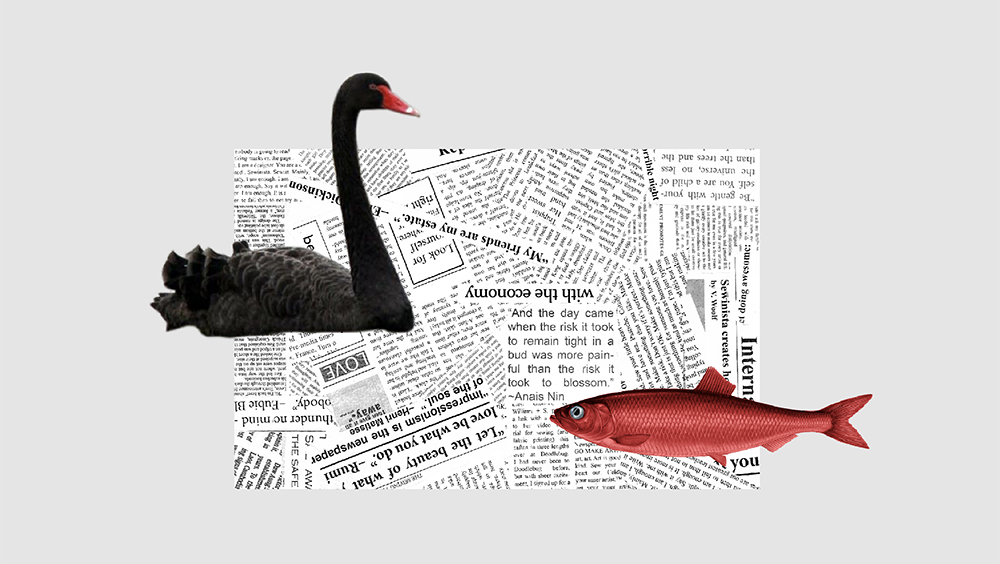

Academics often complain about being ignored by decision-makers. Yet people in power are neither uninterested nor uneducated. It’s the academic way of writing and communicating that’s the problem.

In the late 1990s, a prominent academic researcher joined our NATO policy planning and speechwriting team for a few months. His track record was stellar: he was a lecturer at prestigious universities in several countries, he had published numerous articles in well-known peer-reviewed journals, and he had edited several books on international security affairs.

When our new colleague looked for ways to apply his skills, however, he found it much harder than he had anticipated. He had to realize that a large, consensus-driven organization like NATO tends to be obsessed with process. Even on issues where substance seems paramount, our new colleague had to swallow his pride: our divisional leadership rejected an analysis he had produced on a specific regional issue, because his findings were considered politically and militarily infeasible. To be sure, no one took issue with the quality of his analysis. What mattered was that the conclusions were outside the political comfort zone.

In the end, the acclaimed academic did not really leave a lasting mark on NATO’s evolution. However, he learned a lot about the “real” NATO: a massive, risk-averse bureaucracy, where progress is hardly ever the result of radically new ideas but rather of persistent work in committees, occasionally augmented by offline discussions in cafeterias.

Does this depressing story mean that the security establishment, as epitomized in national ministries or major international institutions, is impenetrable to advice and inspiration from the academic strategic community? Are students of international security affairs, who hope to one day use their skills to make the world a safer place, better advised to become lawyers or businessmen? The answer to these questions is an unequivocal “no.” Academics can make their voice heard, provided they are willing to acknowledge that in the hectic world of practical policy-making, specific rules apply.

Less is More

The number one constraint for virtually all decision-makers and their staff is a lack of time. Any academic who wants to be heard needs to understand this—yet, sadly, all too many academics don’t. The fact that most decision-makers’ briefcases contain a ton of files but probably not the latest issue of Foreign Affairs (or, shock horror, not the Berlin Policy Journal either) does not imply that these people are intellectually weak or even just plain stupid. Rather, they simply cannot afford the time to plough through a 10,000-word article that may contain only one noteworthy idea. Hence their penchant for short, snappy reading, such as op-ed columns in prominent newspapers. Op-eds are not the forum for complex academic reasoning of pros and cons, but concentrate on one persuasive argument.

Some academics are horrified by the very idea of writing op-eds. But one of the counterproductive side-effects of mainstream academic education is the inability of many academics to be brief. All too often, they equate “brief” with “superficial.” Developing a good idea takes time, or so their thinking goes. One researcher, for example, delivered a briefing that featured close to a hundred Power Point slides. In addition, he also kept fifty backup slides in case his audience would ask for an encore (it didn’t!). While this case was probably unique, many researchers feel insulted when they are asked to present their thoughts in ten minutes or less. Yet those who demand such brevity are neither lazy nor do they suffer from attention deficit disorder.

They simply believe—usually based on years of experience—that they will be able to recognize a good idea when they see one, and that this process does not require an hour and a seemingly infinite number of slides.

If academics want to get their points across, they need to make some hard choices: which are the most important issues they want to make, and, conversely, which issues can safely be dropped. Many academics would rather get a root canal than make such choices. They are terrified that by leaving out important stuff, their audience will perceive them as shallow. They need not worry.

Simplicity Is Difficult

The worst mistake next to being too long is being needlessly complicated. As mentioned earlier, decision-makers are not stupid; many of them also went to university, even if their career path took them in a different direction. However, one cannot expect them to be pleased with long, theory-heavy and jargon-loaded presentations or articles that require a Rosetta Stone to translate them into normal language. Sometimes even the most prominent think tankers go down in flames due to their tendency to “show off.”

For example, at a meeting with NATO officials, two think tankers, by using jargon and overly complex graphs, managed to complicate their interesting findings so much that they lost their audience after a few minutes. In the same vein, an expert who presented several trends about the future development of the global energy landscape stubbornly refused to answer the question which of these scenarios he deemed the most likely. Quite obviously, he was terrified that he might be held accountable to a prediction that may turn out wrong.

Many “strategic foresight” experts do the same. They sketch several alternative futures, but avoid being pinned down on any of them. “Foresight,” they tell their baffled audience, is not the same as “prediction.” After all, the future evolves in a “cone of uncertainty.” Maybe so, but decision-makers who are told that a certain issue may potentially evolve in three different ways will be annoyed rather than enlightened. What they need is one plausibly argued case, not three alternatives, which only serve to put the burden back on them and off the researcher’s shoulders.

Originality vs. Realism

Many academics believe that the best way to catch decision-makers’ attention is by being original. Yet nothing could be further from the truth. Decision-makers are not looking for something that is totally out of the ordinary. Rather, they seek incremental ideas that move things forward and that are, above all, achievable. This is why an expert on the political situation in Kosovo, the evolution of Russia’s defense sector, or the strategic implications of China’s Foreign Direct Investment in Europe is more likely to be listened to than someone who pontificates about grander things, such as, for example, the future of NATO, the future of the liberal world order, or similar “big stuff.”

When, to give a particularly stark example, NATO diplomats are told by an academic that the Atlantic Alliance’s decision-making procedures should move from unanimity to majority voting, that NATO should establish a European caucus to better balance the United States, or to abolish NATO’s integrated military structure, these diplomats will be rolling their eyes in despair rather than appreciating these bold ideas. Decision-makers will filter everything they hear through the lens of political or military practicability. Alas, academic advice all too often fails that test. Before one starts thinking “out-of-the-box,” one first needs to know what’s in the box. An occasional provocation may enrich the debate, but academics who consistently go against the grain because they consider it “original” are not original at all. They are just clowns with a university degree.

The Importance of Timing

Academics have time to study an issue in much greater depth than a decision-maker or their staff. This is why bureaucrats, no matter how much they may scoff at the “naïve” eggheads inside the ivory tower, still reach out to academics. However, many academics squander this opportunity. Policy advice is demand-driven. The bureaucrat listens to the academic not for entertainment, but because they have a real-life problem to solve. Hence, timing is of the essence.

A think tanker who once tried to convince a defense minister that NATO’s latest arms control proposal (which had taken the allies ten months to agree on) should be completely revised, provoked only two unpleasant responses: first, he was asked by the minister why developing these great thoughts took him longer than it took almost 30 nations to develop their own proposal. And then the minister cut the meeting short, as he simply was not going to travel to Brussels to make himself a laughing stock in front of his colleagues.

The lesson from this episode is clear: no matter how thorough the academic’s analysis might have been, its bad timing made it utterly useless. The same holds true for ideas that come too early: The academic may come up with a brilliant idea about some future development, yet when decision-makers are busy focusing on other, more current issues, this idea will not have any traction. Even if events finally prove the academic’s predictions right, no one will care. In the noise of daily politics, an idea that is articulated too early is just as lost as the thought that comes too late.

Power Speaks to Power

Our Policy Planning Unit was once asked to examine an idea that the entire team considered utterly silly. We told our leadership that this idea was not worth wasting any time on, yet we were told that our dismissive views were irrelevant and that we should thoroughly look at the issue. The reason for the seriousness with which our superiors approached this task was easy to fathom. The idea in question had been put forward by a high-level official from a most important allied country in a meeting with our own leadership. The proposal made no sense whatsoever; we said so in our analysis, and our leadership quickly lost interest in it.

Yet the lesson was clear: if someone who is considered important and powerful utters an idea—no matter how stupid—it will be treated as an important contribution. Unfortunately, some powerful people tend to not listen to those who have less power, no matter how high their IQ. For example, if the staff makes a proposal for a new political or military initiative, the boss might reject it as too banal or infeasible. Yet if an op-ed by Henry Kissinger or Carl Bildt makes that exact same proposal just a few weeks later, the decision-maker will suddenly find it brilliant and advise his staff to give it further thought.

Let’s be honest: for most politicians and business leaders, a half-baked idea voiced by a VIP at a gala dinner carries more weight than 10 brilliant analytical papers written by their staff or by an academic researcher. In such cases, the academic and the average bureaucrat are in the same boat and have no choice but to accept this most inconvenient truth: when power speaks to power, all other voices fall silent.

Academic Humility

The real-life observations presented here should not lead to the belief that bureaucratic insiders would by definition fare better in getting the attention of key decision-makers than outside experts from academia. True, bureaucrats may have fewer inhibitions when it comes to writing short, un-academic papers, ignoring weighty theories, and offering at least a few recommendations for action. For the hardcore academic researcher this may sound boring, yet getting it right requires a degree of intellectual discipline (and academic humility) that many universities fail to prepare their students for.

Still, the bureaucrat needs the academic. Without academic research, policy-making would run the risk of become ever narrower intellectually. Without the academic’s more thorough inquiry into complex issues, real-life policy-making would become ever more self-absorbed, depriving itself of alternative courses of action, while political leaders would increasingly operate by mere “instinct” (which is mostly a euphemism for half-truths and personal prejudices).

It’s only by working together that they can safeguard the achievements of the Enlightenment that are currently in danger of getting lost: rational analysis and the facts-based search for sustainable solutions.