As the European Union struggles to tackle rule of law concerns in central Europe, EU funds have become the latest battleground over how to uphold European values.

There is no question that 2018 will be another challenging year for the European Union, with Brexit negotiations moving to the next phase, Germany’s prolonged political uncertainty, and Italy’s pending election—but deciding how to deal with the bloc’s increasingly “illiberal” member states might prove to be the most difficult of them all.

Hungary and Poland continue to challenge the EU’s authority as their nationalist governments undermine the rule of law at home and common EU policies on the European stage. Both had refused to comply with an EU decision to relocate asylum seekers from Greece and Italy at the peak of the migration crisis in 2015, and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has made it clear he will not back down.

Meanwhile, Poland’s dramatic overhaul of the judiciary last year created the deepest rift with the EU since eastward enlargement of the bloc in 2004. In December, the European Commission launched for the first time the so-called “nuclear option” – the Article 7 sanctions procedure against Poland for creating a “clear risk of a serious breach of rule of law.” Article 7 was introduced as a check on member states to prevent them from violating European values and the rule of law.

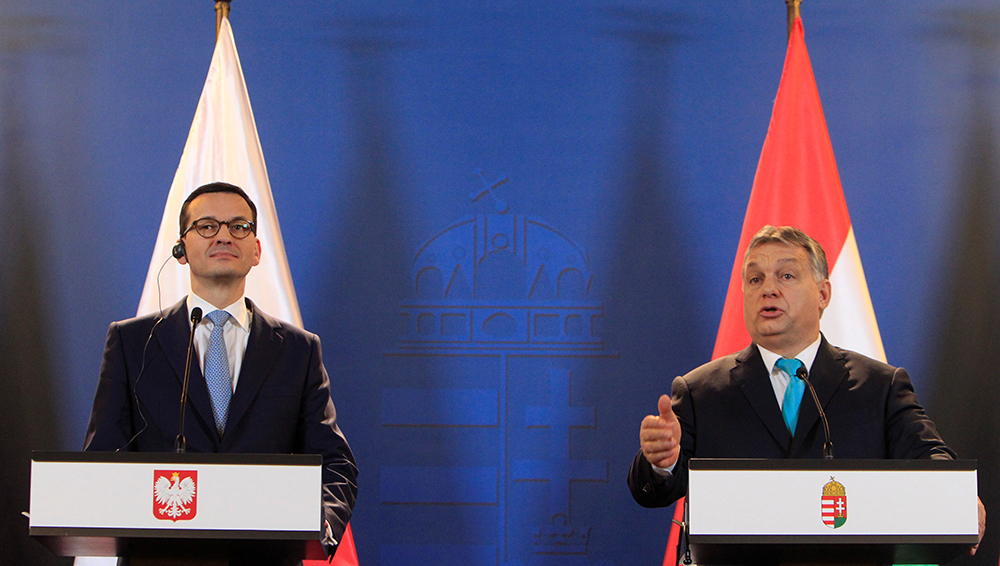

However, real sanctions are a distant possibility: all 27 member states would need to agree to levy sanctions and suspend voting rights, and Hungary has already vowed to veto any decision against Poland. As a sign of the ever-closer ties between the two countries, the new Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki traveled to Budapest on his first official foreign visit in January.

The EU has been trying to align Warsaw and Budapest with EU rules and values at the core of the European project, but it has struggled to tame these two governments on rolling back the rule of law and democracy. A lack of political willingness among fellow member states to sanction one of their peers has been one of the reasons, but the EU also has a poor toolkit to discipline governments on the rule of law.

Frustration Boiling Over

As discussions on the next seven-year EU budget get under way in Brussels this year, there is increasing support among member states who pay more into the EU budget than they get back to tie EU funds not only to economic performance, but also to respect for the rule of law.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel already warned Hungary in September 2017 that it could lose EU funds if it failed to comply with an earlier European Court of Justice ruling on accepting refugees based on quotas. At the end of last October, EU justice commissioner Vera Jourova backed up earlier proposals from the EU executive on tying EU funds to rule of law adherence. “In my personal view we should consider creating stronger conditionality between the rule of law and the cohesion funds,” she said at a conference in Helsinki. “Countries where we have doubts about the rule of law should face tougher scrutiny and checks.”

Juho Romakkaniemi, the head of cabinet of the EU Commission vice president, suggested in a tweet that EU countries might become reluctant to support countries where EU core values are challenged. At a meeting of EU ministers in November, Germany, France, Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, Italy, and Sweden indicated they were in favor of linking EU funds to the respect of the rule of law. Last November several high profile former European officials, including Pascal Lamy and Hans Eichel, also argued for linking up funds with political conditions; they urged the EU Commission to suspend EU funds to Hungary because basic freedoms are being violated and corruption is soaring.

EU negotiations on the next budget will kick off in May, and the proverbial battle lines have been drawn. The stakes are high: the EU allocated €86 billion in structural funds to Poland in the current 2014-20 period, while Hungary is receiving €25 billion during the same timeframe.

As the Commission gears up to present its proposals, the budget commissioner Günther Oettinger in January said the EU executive is looking into the legal feasibility of linking EU funds to the respect for the rule of law. He pointed out that for the conditionality to become reality, all member states would have to agree—making any radical move almost impossible.

What Comes Around Goes Around

Linking EU funds to political conditions goes against the EU treaties, central and eastern European officials argue. “I think these proposals are stillborn. The EU is based on treaties, and there is nothing in there that would create this possibility [of linking funds to the rule of law],” Viktor Orbán said late December in a radio interview. His government spokesman Zoltan Kovacs has called it a form of “political blackmail.” Orbán also warned that the EU budget needed to be approved unanimously among EU countries, so Hungary has ample tools to stop this proposal from becoming reality.

Central and eastern European officials point out that taxpayers in the net contributing countries also benefit from the EU cohesion funds. They say profits on the investments fuelled by EU funds trickle back to the West. Poland’s deputy minister for economic development Jerzy Kwiecinski said in October that for every euro invested in cohesion funds, 80 cents go back to EU-15, the net contributors. Even commissioner Oettinger underlined this notion in an interview in early 2017. “The Poles use the money to place orders with the German construction industry, to buy German machines and German trucks. So net contributors such as Germany should be interested in the structural funds. From an economic perspective, Germany isn’t a net contributor but a net recipient,” he said.

Officials also warn that EU funds are one of the reasons why support for the EU among the population of central European countries is still high despite a general sense of lack of trust in the EU on the continent. Central and eastern European officials controversially argue that EU funds are not charity, but a necessary compensation for opening their markets to the rest of the EU when their post-communist economies were still weak and vulnerable in the 2000s. “Don’t try to suggest that [the] EU cohesion fund is a gift for central and eastern member states,” spokesman Zoltan Kovacs said in Brussels last September.

The issue is politically toxic, as it reinforces the notion in central and eastern Europe that its citizens are only second-class in the EU. But that notion—while alive and well on its own—is being thoroughly exploited by governments in Hungary and Poland. They argue that political conditions alone infringe upon national sovereignty. As discussion over the next budget—which will undoubtedly be smaller than the current one as the UK leaves the EU—heat up, so could tensions among the continent’s eastern and western flank.