Germany is facing intense criticism for its handling of the Greek crisis. However, few remember the obstacles the Merkel government had to overcome to reach an agreement with Athens and keep the eurozone together – some of which were erected by the Tsipras government itself.

The July 13 resolution to start negotiations with Greece on a third financial assistance package was the conclusion of years of wrestling with various Greek governments over the stabilization of the country. Under the 2014 conservative government led by Antonis Samaras, it appeared that Greece would require little more than preventative treatment to avoid a relapse after its second stability loan ran out. When Syriza politician Alexis Tsipras formed his coalition government in January, however – comprised of opponents of the previous European Stability Mechanism (ESM) policy from both the extreme left and right – the shock was felt throughout Europe.

In a matter of just a few weeks, the front lines between Athens and the rest of the eurozone solidified. The country’s sharp economic decline made it even clearer that Greece and its 18 eurozone partners would be forced to answer two questions in short order: Would Tsipras refuse a third Greek bailout to avoid further reform obligations? And would the eurozone partners alter their previous ESM stance, or would they let Greece go bankrupt, and perhaps even tumble out of the eurozone? The situation was complicated by the fact that Greece, as both a NATO member state and a country currently accepting a huge number of Middle Eastern refugees, plays a huge strategic role in general European security. Even the United States was demanding some sort of resolution – especially in the face of Prime Minister Tsipras’ repeated attempts to draw his country closer to Russia.

Trying to Divide vs Trying to Unite

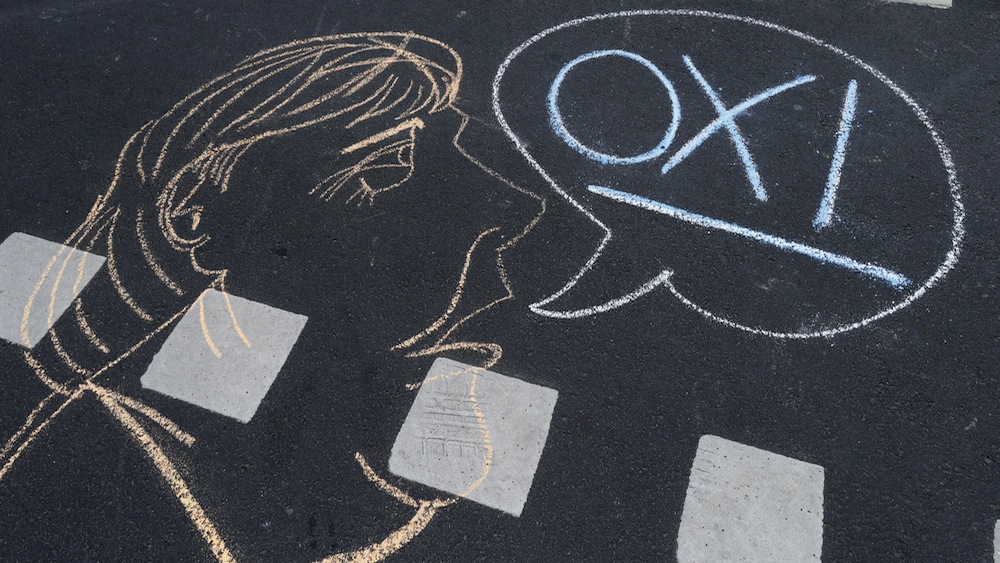

Thus the diplomatic challenge for the German government was completely different than the one publicly acknowledged: from the very beginning, the German government’s goal was to keep the eurozone countries, the European Union, and the transatlantic community from ripping apart. Tsipras, meanwhile, worked to divide the EU and eurozone to reach his political goals. His first diplomatic meetings were with the Russians and the Chinese, not with his European partners. His next stops were eurozone countries with socialist or social-democratic governments and those states from which he hoped to receive the most support: France and Italy. Consciously invoking World War II’s brutal German occupation, he attempted to portray the general debt crisis as one between Greece and Germany alone, reducing the conflict to “solidarity” versus “austerity”.

Following the February decision by the eurozone governments to extend the second rescue program until June 30, the positions of the eurozone’s finance ministers began to harden. From the end of May, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, together with French President François Hollande, sought a “trialogue” with Athens: Tsipras needed to understand that the division of the eurozone into socialist and conservative camps would not work. Athens’ repeated refusal to begin any reforms or guarantee the country’s solvency come July in fact only solidified the unity of the 18 other eurozone governments. Unlike in previous controversies over ESM measures, frustrated Northern and Eastern European governments were now strongly outspoken. For this reason, Germany assumed a moderate position very early in negotiations – a point lost on the media and the critics fixated on Berlin’s actions.

Mouthpiece of the Majority

Following the Greek government’s call for a referendum on July 5, it became impossible for the eurozone to reach any clear consensus on policy: the German government, along with a majority of other eurozone states, attempted to stifle any further discussion until after the results of the referendum, while Hollande publicly demanded new negotiations before said results. At this point, Germany had become the mouthpiece for the majority, whose worries Social Democrat (SPD) party leader and Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel clearly enumerated. The price paid in public opinion for this engagement, however, was quite steep: in the end, many observers blamed the expiration of the second aid program and the imminent Greek default on Merkel and German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble.

It was at the extraordinary eurozone summit on July 7 that a large number of northern and eastern European states made clear that they no longer wished to negotiate with Tsipras – and would rather see the country leave the eurozone. Gabriel had previously stated that Athens had burned its bridges with its referendum vote. It was the impression of most governments that Tsipras knew the danger the referendum posed to his hopes of keeping Greece in the monetary union – and understood that it had in fact weakened his bargaining position with the other 18 eurozone members.

From this point forward, German crisis diplomacy shifted into high gear: on Friday, July 10, the German Ministry of Finance presented its plan – later criticized – to the eurozone’s working group and stated its preference for an extensive program of reforms in return for another multi-billion rescue package. If Greece was unable or unwilling to accept these conditions, the alternative proposal encompassed a five-year “time out” from the eurozone alongside simultaneous debt relief. Given the much harder line proposed by the Finns, Balts, Dutch, and Slovaks, among others, Berlin considered its own proposal not only a warning for Athens, but also a more reasonable position within the 18 eurozone partners. The idea was that it would be better to put the options clearly on the table, and to ensure that Greece’s alternative to an ambitious reform package would not be a chaotic regression into bankruptcy, a danger that was openly discussed at this point. Many eurozone finance ministers later praised the proposal for ultimately increasing the Greek government’s willingness to negotiate. But even the German authors of the paper later acknowledged that they were surprised by the intensity of the response – which, in their minds, only explained the obvious.

In Saturday’s first meeting of the eurozone finance ministers, 15 of 19 euro countries initially refused to negotiate further with Athens on the basis of Greece’s own proposals. When the finance ministers finally got to work drafting a new framework for a third rescue package and laying out what the necessary reforms would be, Germany pushed for the inclusion of numerous demands from its plan – including the idea of a privatization trust and the alternative “time out” proposal – in a draft that was passed, without a vote, at the emergency Brussels summit of eurozone leaders on July 12. But it is important to note that it was France, not Germany, who was isolated in the debates, only supported halfheartedly by Italy and Cyprus.

No “Beauty Pageant”

Only Merkel, Hollande, and EU Council President Donald Tusk negotiated with Tsipras on the fateful night – for 17 hours (incidentally, the same time it took to reach an agreement with Russian president Vladimir Putin in Minsk). Because France was against any eurozone exit, the chancellor and the French president agreed on an early compromise: there would no longer be talk of any temporary eurozone departure for Greece, especially since the idea had already served its function as a warning. In exchange, Hollande supported Berlin’s effort to bind Tsipras to concrete reforms. The Netherlands’ Mark Rutte joined at least once in the nightly debates to show that Merkel’s position was by no means the most radical in the eurozone. Public discussion has largely ignored the fact that eurozone governments included severe language in the agreement largely to make further aid palatable to their publics.

Once again, Merkel had to accept that Germany would carry twice the burden. As the largest shareholder in the ESM, Germany would assume the lion’s share of any new loan guarantees. And further, unlike in the wake of the Minsk resolution, Germany would face severe criticism for its role: there was talk of a “German diktat” or even a “coup” (on Twitter, the hash tag #thisisacoup trended that night). But Merkel chose a hard tone in her final press conference at the end of the special Euro-summit, mainly for her domestic audience – she had to make sure that she would get new agreements approved by both the Bundestag and skeptics in her own party.

The third “price” Merkel had to pay was tension within her coalition. The act of openly putting Grexit on the table itself created tensions between the German government’s coalition partners. Pressure in the SPD, the coalition’s junior partner, even led party chief Gabriel to distance himself from the Grexit-proposal. However, Merkel and Schäuble, the negotiators, said afterwards that they saw no alternative to being open about what was and is at stake. It’s not about “beauty pageants and popularity contests,” said Merkel later, explaining why there had been no alternative way to reach an agreement.