Lives across Europe have been turned upside down by the pandemic, with eerily quiet streets and families at home grappling with uncertainty—many of whom are turning to Steven Soderbergh’s movie Contagion or Albert Camus’ 1947 novel The Plague (its publisher is struggling with so many orders), perhaps hoping to distract themselves with past or fictional health crises.

But stranger than fiction, some governments around the world—most notably the Brazilian administration of President Jair Bolsonaro, who fired his health minister and is encouraging young people to go on with their lives as usual—have downplayed the importance of social distancing. Also, the Swedish government has not implemented lockdown measures seen elsewhere.

Other governments reacted more decisively to stop the spread of the coronavirus. They realized that the cities that reacted to the 1918 influenza outbreak, the Spanish flu, early on, by shutting schools and banning gatherings, were able to limit fatalities. The Portuguese government, for instance, reacted before any COVID-19 deaths had taken place, and had more time to prepare due to the country’s location on the edge of Europe, among other factors. Local transmission happened later than in neighboring Spain, where at the end of April, there were over 230,000 people infected, compared with around 24,000 in Portugal, according to figures from Johns Hopkins University on April 27, 2020.

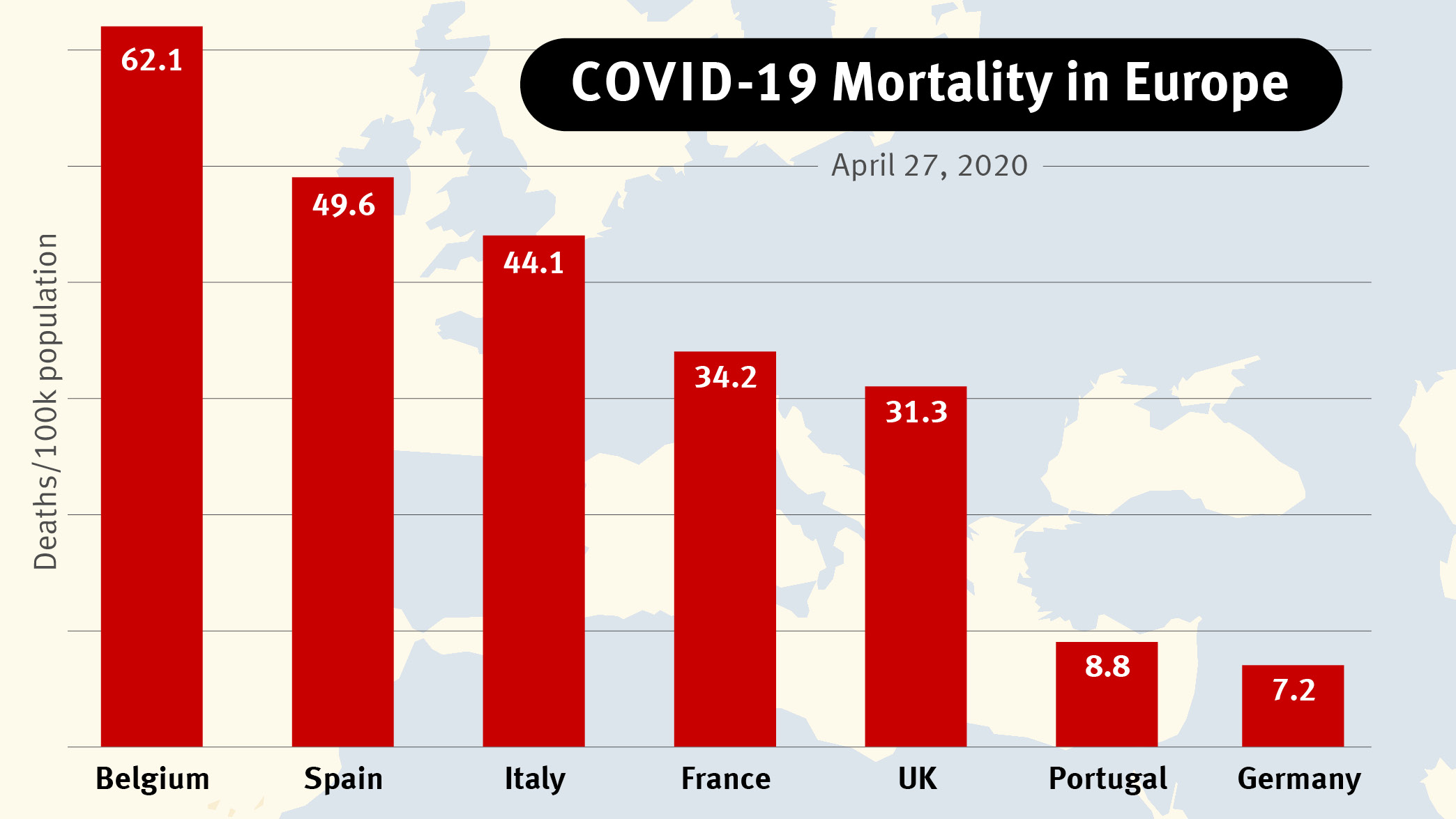

The difference is even more stark when looking at the deaths-per-100,000 inhabitants ratio. The figure for Spain is 49.6, while Portugal’s is 8.8. However, it’s not generally true that small countries do better. Belgium counted 62.1 CORVID-19 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, compared to Germany’s 7.2. Europe’s other big countries have done much worse; the figure for Italy is 44.1, for France 34.2, and for the United Kingdom 31.3.

Two Weeks Behind

“This is not a ‘Portuguese miracle’ and we have not reached the end of the pandemic to be able to make an assessment,” Filipe Froes, the head of the intensive care unit at Lisbon’s Hospital Pulido Valente and an advisor to Portugal’s health minister, told me.

“Portugal benefited from the fact that we are two weeks behind Spain,” Froes pointed out. “We declared a state of emergency and measures of confinement at the same time as Spain and Italy and used those precious days ahead to increase the response capacity in hospitals as well as involving primary health care, so that infected patients could be treated in ambulatory care.”

Portugal could have done even better, though, Froes pointed out, had it controlled people on arrival at Portuguese airports. “There should have been an articulated response within the European Union. Just like it has economic measures it should have collective measures for health too,” he argued.

Countries in the EU have diverged on social isolation measures, money, medical equipment, and border restrictions. But one thing all these countries have in common is overworked staff in hospitals and lack of some basic equipment. Sonia Lontrao, a nurse at Lisbon’s Egas Moniz hospital, told me that medical staff like herself are working 12-hour shifts with minimum protection, putting their lives at risk.

The EU was criticized in particular for abandoning Italy during the outbreak. China stepped in to provide assistance, whereas Italy’s request for help from the Union Civil Protection Mechanism initially came to no avail. However, the EU Civil Protection Mechanism did end up sending nurses from Romania and Norway to help Italy, and Austria offered 3,000 liters of disinfectant. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen offered “a heartfelt apology.”

The Trillion Euro Fight

Not everyone is in apologetic mood, though. Portugal’s prime minister, Antonio Costa, recently blasted Dutch Finance Minister Wobke Hoekstra for asking the European Commission to investigate countries such as Spain and Italy for not having a financial cushion to allow them to face the COVID-19 crisis, saying his words were “disgusting.” EU finance ministers then settled on an agreement to approve a financial support package worth half-a-trillion euros. It includes €200 billion, which the European Investment Bank will lend to companies, and €240 billion in credits which the European Stability Mechanism bailout fund will make available to governments. This brings the EU’s total fiscal response to the epidemic to a least €1.2 trillion.

“It’s too early to celebrate, as none of the details have been figured out,” Mujtaba Rahman of the Eurasia Group told me. “Russia and China have intervened, to try to bolster their influence in parts of Europe where Brussels has not been forthcoming. Whether that can now be corrected with the EU’s response to the economic fallout is an open question, but the initial signs are not very promising,” Rahman added.

EU cooperation may be falling short, yet the epidemic has brought to light sporadic acts of kindness. People are looking out for vulnerable neighbors and sewing masks. Camus’ daughter, Catherine Camus, told The Guardian that the main message in her father’s book, The Plague, was that we are responsible for our actions. “We are not responsible for coronavirus but we can be responsible in the way we respond to it,” she said.