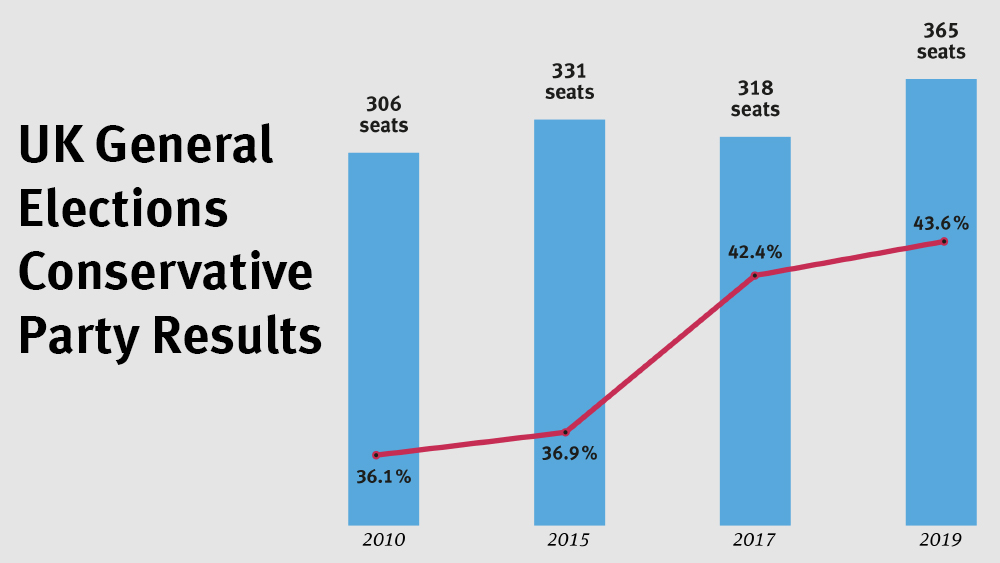

By winning 365 of the 650 parliamentary seats, Boris Johnson’s Conservatives have changed Britain’s political landscape for the next five years, possibly for the next decade. After the last three to four years of knife-edge votes and parliamentary paralysis, the coast will be clear for them to introduce whatever legislation they wish.

The 80-seat majority at the December 12 election was at the very top end of predictions, indeed beyond the expectations of most Tory strategists.

Johnson will move quickly. He will have learnt the lessons of Tony Blair, who failed to capitalize on his landslide in 1997. Brexit will take place on January 31, this time without any last-minute hiccups. A budget will be introduced in March that is likely to include spending commitments on the National Health Service and infrastructure, particularly to reward his new-found voters in the North of England and the Midlands. Expect also early decisions on a series of ideologically driven challenges to the civil service and the BBC, two right-wing pet hates.

A detailed analysis of the results suggests, however, that overall support for the Conservatives is by no means as comprehensive as may initially have seemed.

Leave United, Remain Divided

Their big margin of victory can be attributed to three factors—the demographic particularities of Brexit, the electoral system, and clever strategizing.

Brexit: the Conservatives were clear winners in constituencies that voted Leave in the 2016 EU referendum. They won almost three quarters of all these seats. The writing was on the wall for pro-Remain groups when Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party announced at the start of the campaign that it would not compete in constituencies that the Tories were defending.

The Leave caucus found itself united. By contrast, the Remain one was not. Some small-scale alliances were formed involving the Liberal Democrats, Welsh nationalists, and Greens; but these were marginal and had very little effect. The fact that the Lib Dems (who had advocated revoking the original Article 50 decision) and Labour (who couldn’t quite work out what its position was) fought furiously against each other was a gift to Johnson.

As a result, the Remain vote was split, with a crowded field of parties sharing the seats between them.

The Conservatives won an impressive 294 of the 410 seats that had opted to get out of the EU. Labour secured only 106, in spite of Jeremy Corbyn’s refusal to accede to the demands of most of his parliamentary party to endorse a second referendum.

Corbyn Trumped Brexit

His equivocation on the issue didn’t do him an enormous amount of good on the other side of the divide either. Of the 240 seats that had a majority opting to remain in 2016, Labour won only 96. The Conservatives trailed, but not by much, with 71, confirming the assertion that Johnson’s role in securing Brexit was regarded as less of a threat to voters than the prospect of a Corbyn government. In heavily pro-Remain Scotland, the SNP pro-independence and pro-EU party won a hugely impressive 48 of the 59 seats available.

The constitution: Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system was designed to ensure “strong” government. This is in direct contrast to, say, Germany or other countries, where consensus is regarded as the goal. That is why the UK has had so few coalitions. Even though the one it had between 2010 and 2015 involving the Conservatives and Lib Dems was stable, conventional wisdom has been hostile to any change in the way votes are distributed.

One can understand why any governing party would be resistant. The winner has a disproportionate amount of power. On a purely proportional system, the UK would have had a hung parliament, and the Tories’ 43.6 percent share of the vote would have required them to try to create an alliance with another party. The Lib Dems and Greens have long been the biggest losers in the present system. This time was no different.

The message: Conservative strategists realized long before Johnson called the election that they did not need to be popular. They needed merely to emphasize the unpopularity of Corbyn. The plan worked perfectly. Labour had their worst return of seats in any general election since 1935. They fell backwards in every region of the UK, declining by an average of 8 percentage points. In the northeast of England, their previous heartland, they shed 13 points—almost all of the swing going to the Tories. Even in the most affluent London and the southeast, they lost over 6 percentage points—mainly to the Lib Dems.

The following figures perfectly demonstrate the unfairness of the system. The Lib Dems gained an extra 4 percent of voters, yet lost one seat, ending up with a paltry 11. The Greens and the SNP went up too. The Tory vote only increased by 2 percent overall, but in spite of that small rise, they are seen to have triumphed.

Thanks therefore to a skewed voting system, an unpopular Labour leader, smart Tory strategy, and the failure of pro-EU parties to unite, the UK faces a long period of hegemony by a right-wing populist-nationalist party voted in by less than half of the population. That is the depressing state of Britain’s constitution and political culture.

A More Diverse Parliament

Yet some other data suggest that long term trends may be different. Northern Ireland, on the front line of the Brexit battle, now has for the first time more nationalist than unionist MPs. Parliament will have a record 63 members who come from an ethnic minority, an increase of 11 from two years ago. And a total of 220 women have been elected. This is 12 more than the previous high of 208 in 2017 and constitutes just over a third of the total number. Labour and the Lib Dems have more female than male MPs.

A more diverse parliament, just like a more diverse corporate boardroom, is a good thing in itself. Whether it produces a different mindset is much harder to say.

What is clear from these results is that the United Kingdom is a patchwork of voters with very different backgrounds and priorities. That one party and prime minister have acquired unbridled power, in effect able to do whatever they like for a minimum of five years, is the most dangerous of the many quirks in the British system.