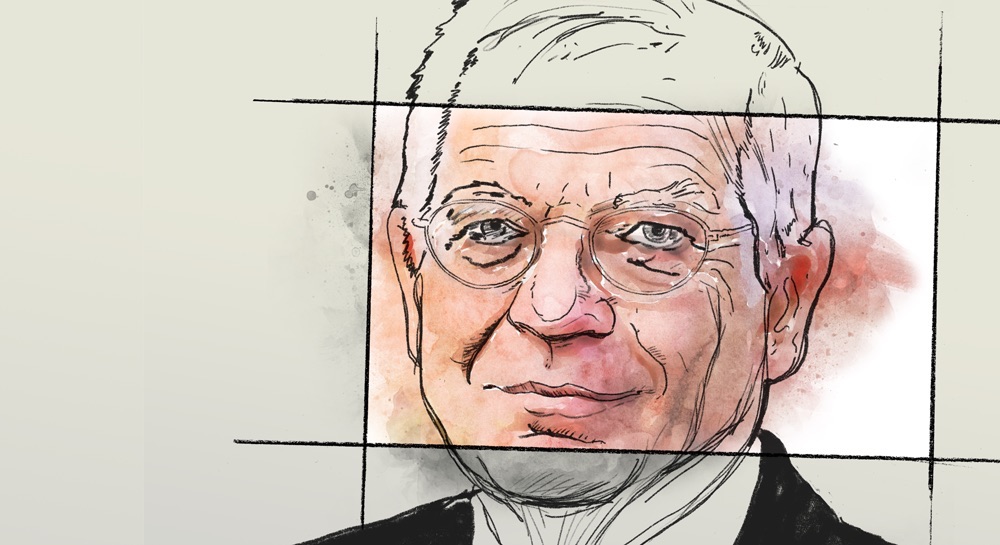

He doesn’t suffer fools gladly, is a master of detail, and his defining traits are intensity and determination. The formidable Josep Borrell is about to take over as Europe’s chief diplomat, and he will strive to make the EU a heavyweight in international affairs.

The life of Josep Borrell Fontelles, the next high representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Vice-president of the European Commission, is extraordinary, as is the man himself. The son of a baker, he was born in 1947 in the small town of La Pobla de Segur, in the Catalan Pyrenees, near Andorra.

After attaining several degrees in aeronautical engineering and economics (including a masters in oil industry economics and technology in Paris) he had a doctorate by the age of 29 and was a full professor in economics at Madrid’s Universidad Complutense by the age of 35. He then turned to politics, becoming secretary of state for the Treasury at 37 and then minister of public works and the environment under the Socialist PSOE government of Felipe González at 44.

He became president of the European Parliament at 57, president of the European University Institute at 63, and then returned to Spanish politics to serve as minister of foreign affairs under Pedro Sánchez. Now at the age of 72 he is to become the chief diplomat for 500 million Europeans, with 4,000 civil servants under his command––quite an intense journey even for such a brilliant mind.

Intensity is actually one of Borrell’s defining character traits. His drive and single-mindedness have brought him great success. He was responsible, for example, for the modernization of the Spanish tax system, including the introduction of VAT, necessary to finance the welfare system when Spain entered the EU in the mid-1980s. In the 1990s he also played a key role in the decision to start building much of the infrastructure that today makes Spain the envy of the world. No small feat.

A Loner, Not a Team Player

However, his strong character and occasional irascibility have sometimes worked against him. At the core, Borrell is a mathematician, and an exceptional one. Not many Spaniards would have been able to get a Fulbright scholarship in the 1970s, still under the Franco dictatorship, to study Applied Mathematics at Stanford University. Yet he did. This outstanding mathematical mind allows him to be Cartesian in his approach to problem-solving but also means that he can easily become impatient when things don’t work out. This is reflected in his favorite hobby: hiking. Having been born in the mountains, wherever he goes he is immediately looking around for the highest mountain to climb.

Hiking, though, is more an individual than a group effort, and that is also one of Borrell’s traits. He is more of a loner than a team player. His intellectual mind is somewhat allergic to social conventions. In a country obsessed with football, he does not like the sport. He also hates networking (maybe the reason he never led the PSOE, although he was close in 1998 when he won the support of the party base). This does not mean, however, that he does not have a full book of contacts. Even after he left power, people would call him to pick his mind. This is a sign of his strong personality and independent thinking.

Recently a senior official at the German Foreign Office told me that Borrell needed to be brave. He must help unite the Europeans internally (starting with the European Commission led by Ursula von der Leyen) and project European power externally. If courage is required, Borrell has tons of it. Keen on rafting and other extreme mountain sports, he does not shy away from a good fight if he is convinced it is for a good cause. Already as a junior civil servant he fought his bosses, voicing his opposition to the first fiscal amnesty of the González era, and more recently he stood by Pedro Sánchez when the PSOE apparatus wanted to get rid of the leader and very few thought he had any chance to become the Spanish prime minister. Yet another example of Borrell’s determination paying off.

What You See Is What You Get

People who work under him highlight that Borrell is extremely demanding, and that this also extends to himself. Slightly workaholic, he prepares the dossiers in-depth and tries to look at the problems from different angles. He has a critical mind and is always looking for improvement. And above all, he is sincere. He does not suffer fools gladly. What you see is what to get with Borrell. This makes him come across as blunt but has also given him the courage to criticize obvious misbehavior.

In 2006, as president of the European Parliament he told Russian President Vladimir Putin face-to-face in a summit in Lahti, Finland, that he was a human rights offender. Later, in 2010, when, in the middle of the euro crisis, he became the president of the European University Institute in Florence he also dared to tell the faculty that they should climb down from their ivory tower and do more policy-oriented research.

This brought positive changes, like the introduction of the now well-established “state of the union” conference, the Migration Policy Center, and the Global Governance Program, as well as the chairs on the “Governance of EMU” and “Energy and Climate Change.” However, it also led to a conflict of interests for being on the board of the energy firm Abengoa and his ultimate resignation. This was not the last time his involvement in Abengoa would give him headaches. In 2015 he sold €9,000 worth of shares belonging to his wife with insider knowledge and was later fined. But overall it is clear that Borrell has never used his power to get rich. His austere lifestyle proves that.

Hatred of Catalan Separatism

The biggest fight of his political life has been with the Catalan separatists. Influenced by the French state culture, which earned him the reputation for being something of a “Jacobin,” he has never understood the obsession of so many of his fellow Catalans with the creation of an independent state. Borrell is proud to be Catalan, speaks Catalan, but has always hated Catalan nationalism. This has been a thorn in the side of secessionists. His successful career has been a vivid example that Catalans are not oppressed by the Spanish state.

He has also sought to counter the idea of the “economics of independence” by publishing a book entitled Las Cuentas y los Cuentos de la Independencia (“The numbers and fairy tales of independence”) where he contests the myth that Catalonia pays annually €16 billion into the coffers of the Spanish state. And he also gave a significant speech on October 8, 2017 (one week after the referendum which Spain declared illegal) in Barcelona in front of 1 million people calling for the unity of Spain. His speech showed that he is a convinced Catalan, Spaniard and European, who is adamantly opposed to any form of ethno-nativist nationalism.

This open Weltanschauung—already as a young student he left Spain to work on a farm in Denmark and in the construction sector in Germany, and he even spent some time in an Israeli kibbutz—will be useful for his job as high representative for the EU. In a time when US foreign policy has become much more nationalistic and reemerging powers like China have become more assertive, the chief European diplomat needs to be a tough negotiator, but also someone convinced that the multilateralist path is the right one.

Dealing with China

A lot of his attention over the next five years will no doubt be devoted to problems in the Middle East and North Africa, including issues like migration and Iran. The future of Africa will be a big dossier too. But hiker Borrell needs to look for higher peaks. Dealing with the Chinese challenge is one of them. Strategically it might be the most defining issue during his mandate. And here, he is convinced that only engagement and cooperation are viable routes.

In short, Borrell will be different to his predecessors. He will not try to find the lowest common denominator in foreign policy. After thinking hard about the problem at hand, he will present his vision and negotiate his way through in order to find a consensus for it. He is determined to make the EU a heavyweight in foreign affairs, expanding today’s G2 into tomorrow’s G3. His experience and determination will be his main advantages. As a convinced European, I wish him luck.

Editor’s note: Watch out for our November/December issue which will focus on European foreign policy.