Should the EU economy run on uranium? Its two biggest countries disagree.

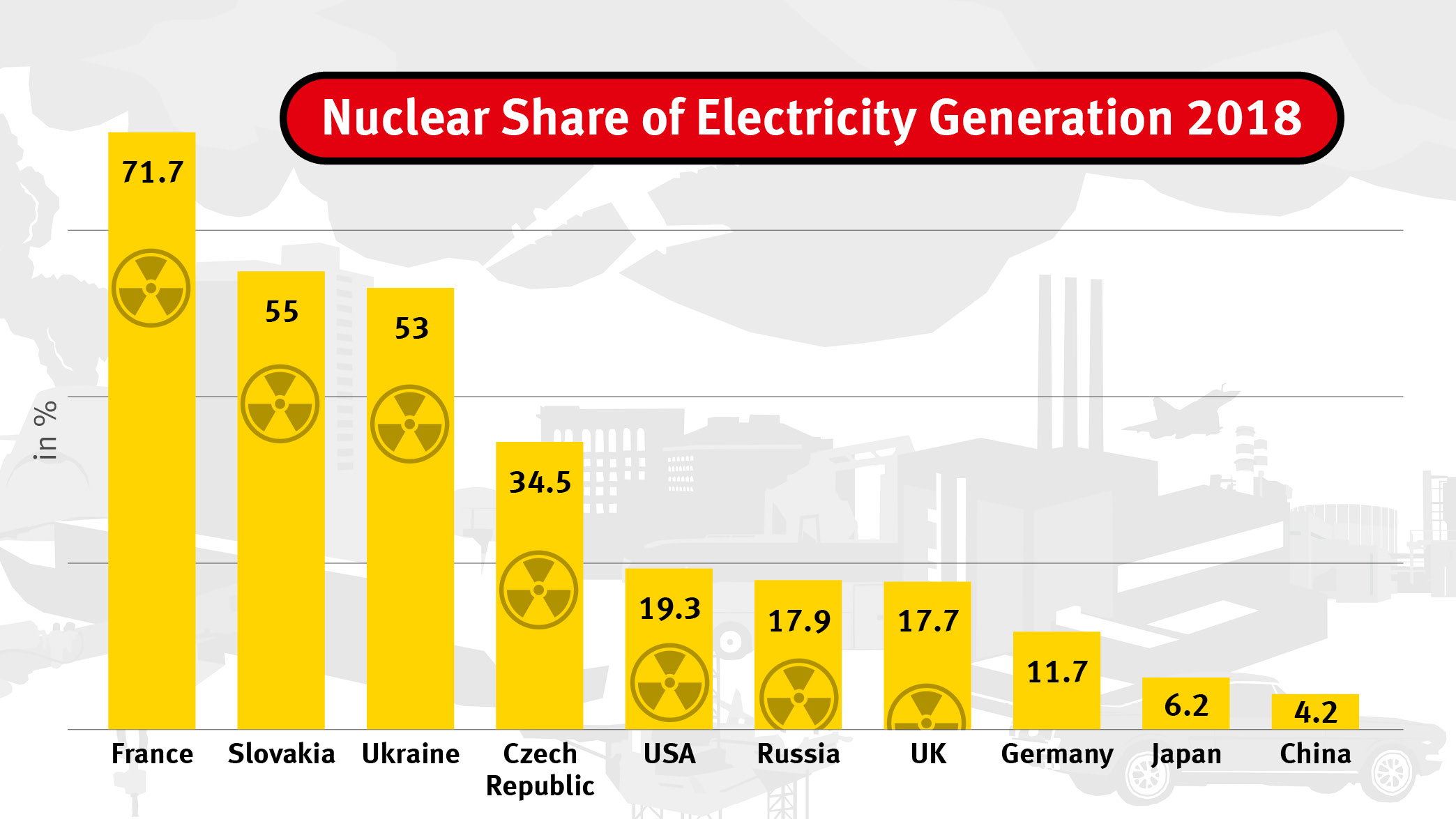

source: IAEA

They are the EU’s two largest member-states, the countries meant to drive European integration forward as the Franco-German motor. The problem is they don’t agree on which fuel to use.

France is a world leader in nuclear power, a low-carbon energy source. About 71 percent of its electricity comes from its 58 nuclear power plants. The state-owned energy giant EDF is building another one in Flamanville, Normandy, a plant that uses an improved “third generation” reactor technology, the European Pressurized Reactor. The average French person emits 7.2 tons of CO2 equivalent per year. Electricity in France costs €0.18 per kilowatt hour.

Germany has given up on nuclear power. It gets less than 12 percent of its electricity from nuclear, and that figure is falling: Germany plans to shut its remaining nuclear power plants by the end of 2022. The average German emits 11.3 tons of CO2 equivalent per year. Electricity in Germany costs €0.31 per kilowatt hour, nearly double the price in France.

The two countries’ differing positions on nuclear power mirror the divide within the EU and within the global environmental movement. As usual with the Franco-German motor, culture and history help explain the differences.

Is Nuclear History?

France made a big push to switch to nuclear power in the wake of the 1973 oil shock—at the time, most French electricity came from oil-burning plants. Because France has relatively small fossil fuel reserves, the idea of switching to uranium, a fuel so potent that one half-inch pellet of it contains as much energy as a ton of coal, had its attractions. There is a proud French tradition of large, centrally directed technological projects, like the high-speed TGV trains that were redesigned to run on electricity rather than gas in the 1970s. State-owned French firms have led the way in exporting technical know-how and building nuclear reactors abroad, and nuclear advocates around the world admire France’s practice of recycling spent fuel to reduce waste. Nuclear power has been broadly popular in France.

It is the problem of storing nuclear waste for the long term that has aroused the most opposition; support for nuclear has fallen over the past few years. A 2018 Odaxa poll found that 53 percent of French opposed nuclear power, up from 33 percent in 2013—though only 28 percent were willing to pay more for their energy to avoid using nuclear.

France, like every other country, is still seeking a permanent underground repository to bury its spent fuel in. It hopes to open one in 2022, but these dates are rarely set in stone: lawsuits from environmental groups and NIMBYs (Not In My Back Yard) have prevented the opening of storage facilities everywhere from the United States to Sweden. It appears that Finland will be the first country to open such a permanent repository, and it’s a good thing too. Regardless of how many new nuclear facilities humans build, the world needs somewhere to store existing radioactive waste, which is currently kept in increasingly overcrowded temporary storage, i.e. in deep pools of water until it cools, and then in casks of thick metal.

And Germany? Nuclear power used to be a big part of the German electricity mix too, peaking at about 30 percent in 2000, but there was always more public opposition east of the Rhine. There were major protests in 1979 after the (non-fatal) meltdown at a nuclear plant on Three Mile Island in New York, and the anti-nuclear movement was a major player in the formation of the Green Party the following year. Fears that Germany would be the battleground for nuclear war between the US and the Soviet Union, combined with the relative proximity of the meltdown at the dreadfully mismanaged nuclear plant in Chernobyl in 1986, did nothing to persuade a skeptical public.

Germany built no new plants after 1989, and the Social Democrat-Green government decided in 1998 to exit nuclear power by 2022. Then in 2011, the Bundestag roundly supported Chancellor Angela Merkel, who initially had wanted nuclear plants to run longer, when she made a U-turn after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan. A quicker end to nuclear power and a big shift to renewable energy, the so-called Energiewende, became the German consensus. Remarkably, the climate-conscious country will now end nuclear power production by 2022—the same year France will stop burning coal—but continue to burn dirty coal for electricity until 2038.

The upshot is that Germany’s impressive expansion of renewables over the last decade has not reduced emissions as fast as it could have, because one form of low-carbon energy has replaced another: before the coronavirus shutdown, Germany was on track to miss its climate targets for 2020. Although groups within Merkel’s conservative Christian Democrats (CDU) and the opposition pro-business Free Democrats (FDP) question whether quitting nuclear was the right move, the issue is dead and buried for much of the population, especially the ascendant, religiously anti-nuclear Greens.

The Price of Power

So France has cleaner, cheaper energy than Germany, though the story is more complicated than that—nothing about splitting nuclei is simple. Those cost/kilowatt hour statistics will have raised the hackles of people on both sides of the nuclear power debate. “How can one put a price on avoiding a Chernobyl-like nuclear disaster?,” a German climate activist might ask. “What is the value of getting out of nuclear energy if the result is higher dependency on Russian gas?” a French bureaucrat might retort.

Both would have a point. The fact that the price tag for energy does not reflect its true cost is central to the climate debate, indeed at the heart of it. Those figures do include the high taxes and fees Germany levies on electricity in order to support the expansion of renewables. But they do not fully capture all sorts of other costs, from the cost of emitting deadly air pollutants and greenhouse gases, to the cost of building a grid that can get renewable power where it’s needed on cloudy, calm days, to the cost of spreading around nuclear technology.

Reasonable people can have different opinions on the extent to which nuclear power should be part of a decarbonized future, and that’s exactly what’s happening with Germany and France, and with their allies within the EU.

Far from Atomized

This isn’t the usual split between “old” and “new” member states, or between the North and South. Spain, Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland have decided to ditch nuclear energy. Denmark, Ireland, Portugal, and Austria never had any commercial nuclear reactors. On the other side stand France, Poland, Finland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, as well as former member the United Kingdom, which all plan to build new reactors. Within the EU as a whole, renewable energy accounts for 14 percent of energy, nuclear energy for 12 percent.

This doesn’t mean the pro-nuclear camp thinks reactors are a silver bullet—even France wants to close some old reactors and increase renewable production so that nuclear power’s share of electricity generation falls to 50 percent by 2035. But some European leaders are determined that nuclear be a part of their low-carbon future. “Nuclear energy is clean energy,” Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš argues. “I don’t know why people have a problem with this.” The Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovakia could only be persuaded to sign up for the European Green Deal in December 2019 because the European Council agreed to respect the “right of the member states to decide on their energy mix… Some member states have indicated that they use nuclear energy…”

Germany disagreed, as it had in September 2019 when EU ministers decided not to exclude nuclear from a sustainable finance classification scheme. “Nuclear energy is neither safe nor sustainable nor cost-effective,” said German State Secretary for Energy Andreas Feicht. “So we reject the idea of EU money to extend the life of nuclear power stations.”

Yet it was the German co-leader of the Green group in the European Parliament, Ska Keller, who broke from her party colleagues to vote for the November 2019 resolution declaring a climate emergency in Europe. Forty-six of her fellow Greens voted against the resolution because of a clause saying that nuclear energy could “contribute to the achievement of climate goals,” resulting in the strange optics of Greens rejecting a measure that for decades they could only dream of passing. Clearly, nuclear reactors have the power to split the environmental movement down the middle.

The Wrong Enemy

One reason that decarbonizing energy systems is so hard is that it isn’t enough to simply replace all current fossil fuel power plants with low-carbon sources. The world needs much more than 100 percent of current electricity, for the millions of people in poor countries who struggle to access electricity, for the electrification of the automobile, for creating carbon-free hydrogen to heat homes.

It’s not for nothing that in every IPCC scenario for limiting global warming to 1.5 Celsius, nuclear power supplies more energy in 2050 than it does now. Nuclear has its drawbacks, especially the massive cost of storing waste. There’s no such thing as a free lunch with energy, however. Fossil fuels are reliable, but they are melting icecaps and clogging lungs. Modern renewables like wind and solar are ideal, safe energy sources, but today—nearly 30 years after the first UN treaty on climate change, as country after country misses its climate targets—they still account for only around 10 percent of total final energy consumption.

Perhaps the next generation of nuclear reactors—meant to be cheaper, smaller, safer, and standardized—will succeed beyond expectations, making nuclear energy the backbone of future low-carbon energy systems. For all the talk of China’s construction of coal power plants, the country is also building 15 new nuclear reactors. Nine years after the Fukushima disaster, Japan is restarting some of its nuclear reactors too. Or perhaps nuclear will fizzle out as the cost of renewables and batteries continues to fall. After all, that French plant at Flamanville is even more over budget and behind schedule than Berlin’s long-delayed new airport.

The next generation of climate activists, who come to the issue with fresh eyes, might give nuclear another chance as the cost of the energy status quo gets higher and higher. Greta Thunberg has said she is “personally against nuclear power, but according to the IPCC, it can be a small part of a very big new carbon free energy solution.”

Good for Greta. Those concerned about climate change have a responsibility to watch carefully the development of nuclear power and make unbiased, evidence-based decisions. They must, to paraphrase Thunberg again, listen to the scientists, even when they don’t like the answer.