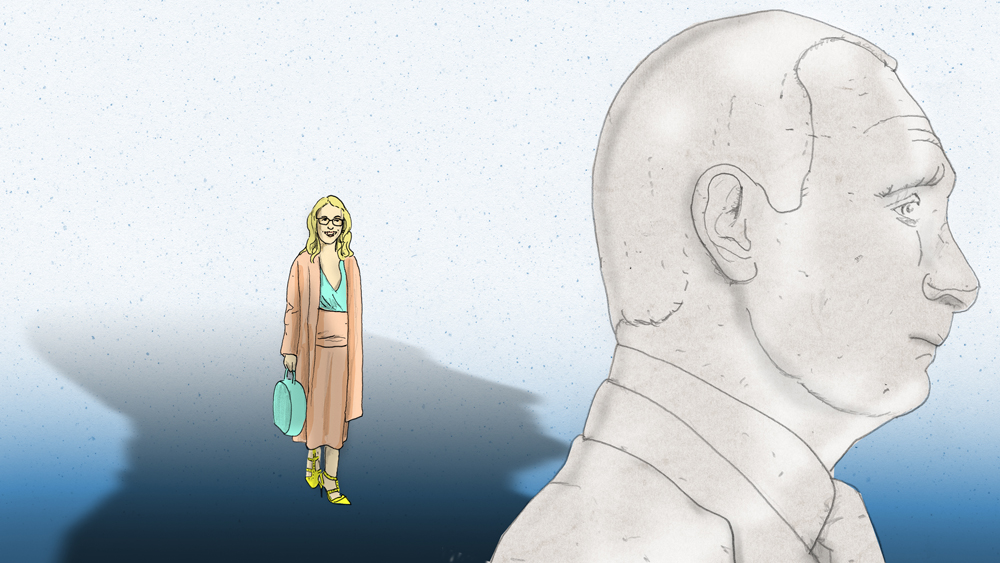

The Russian hashtag #protivvsekh, or “against everyone,” is Ksenia Sobchak’s presidential campaign slogan. But it seems everyone is against the controversial reality TV diva, whom some consider a Kremlin dummy.

Ksenia Sobchak is so convinced of her protiv vsekh motto that she’s even thought of changing her last name to Protivvsekh. And this, mind you, is the daughter of Anatoly Sobchak – the first elected governor of Saint Petersburg, a famous politician and, not least, Putin’s political godfather who died in 2000.

The young Sobchak is anything but a typical Russian political activist. She used to host a popular TV show that resembled Big Brother, but with far more explicit language and sex scenes. That earned her a reputation as the Russian Paris Hilton. She is quick on the trigger, whether in her current job as a journalist at the opposition online site TV Rain, as the editor-in-chief of the fashion magazine L’Officiel Russia, or in response to her many online detractors who brand her as ugly and dumb.

Russian liberals don’t think she is dumb, however, but rather a dummy candidate chosen by the Kremlin to legitimize Vladimir Putin’s victory. As the chances are low that anti-corruption activist and Putin challenger Alexei Navalny will be registered (due to his conviction on trumped up embezzlement charges), Sobchak remains a token opposition candidate, whom Putin will beat handily.

It is once again an example of the vicious dichotomy of how the Russians view politics: if one is stopped from running against Putin, that’s because one really is a threat to him (Navalny); if one is allowed to challenge Putin, that means one is already part of his grand plan (Sobchak). Hashtag Protivvsekh, hashtag Russia.

Another problem facing Sobchak is that she is not an alpha male, which means she is already a lost case in Russian politics. No wonder her presidential bid was followed by a mocking array of female journalists, media personalities, and even an ex-porn star announcing their candidacies (the last is still too young to run). There is a joke currently making rounds that older Russians are nostalgic for the times when Clinton and Sobchak used to be two men.

A Team Player

Ksenia Sobchak, like Navalny, became politically active during the wave of mass protests in the winter of 2011-12. Since then, she has been a staunch critic of Putin’s regime and a vocal proponent of change and reform. She is very straightforward about Stalin’s legacy (“a butcher and a criminal”) and – unlike Navalny – unequivocal on the Crimea question (“according to international accords, it is Ukrainian territory”). Plus, she is ready to be a team player: she has promised to set her own interests aside and withdraw her candidacy if Navalny gets registered.

At the same time, Sobchak has never been liked, and her disapproval rating, currently at 16 percent, is the highest among Russian public figures. According to a poll by the Moscow-based survey institute Levada Center at the end of October, Sobchak is less popular than the very unpopular Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev (13 percent) or Navalny himself (12 percent). Putin’s disapproval rating is just six percent.

The chances of a liberal candidate gaining ground in Russia are slim in any case: according to the same Levada Center poll, only one percent say they would vote for Sobchak.To put that in perspective, Putin would get 53 percent of votes; Navalny 1.8 percent. Interestingly enough, however, nine percent of those who said they might vote for Sobchak are Putin supporters, the undecided, or traditional non-voters.

It is difficult to judge if Sobchak is being manipulated by the Kremlin. She is clearly not easy to control. Her statement on Crimea was radical, even for Russia’s liberals. Sobchak knows that no one can successfully run against Putin. So, as an experienced show business professional, she has vowed to mobilize disillusioned voters, even if that means they do not vote for her. Basically, she wants to put the “against all” option back on the ballot.

Last year’s parliamentary elections had a record low voter turnout – in some cities, only 28 percent of those eligible took part. Perhaps #protivvsekh best describes the general attitude of Russian society to politics and politicians these days.