A new, illiberal order is challenging our open society and democratic institutions. In order to defend our principles, politics, society, and the media will need to brace themselves for a fight.

The specter of an attack on Germany’s critical infrastructure has long been a deep concern for security services – power plants and electricity networks offer prime targets for cyberattacks, and authorities have redoubled their efforts to make sure they are protected.

This hardware is without doubt a central piece of Germany’s basic security. But the country is now facing a larger, more menacing threat to its software. Liberal democracy – the cornerstone of our society – is at risk. And the events of 2016 have shown that we urgently need to confront this threat before it erodes the foundations of enlightened debate.

At first glance, the hacking of the Democratic Party in the US, the proliferation of fake news and propaganda on social media, the rapid rise of nationalist populist movements and parties, and increasingly aggressive Russian secret service operations do not seem to have much in common. But these phenomena are very much connected. And we as a society have taken far too little action to protect our liberal democratic order from dangerous forces.

A new, illiberal order has risen on the back of populist protest movements in the US and Europe. Russia and other anti-democratic actors have aided them, using the very framework of our open societies to their advantage. And Russia’s propaganda campaign has played a central role. It is true that there have long been illiberal movements in liberal societies, and democratic institutions bear some responsibility for the loss of trust and confidence among certain social groups. But ignoring or concealing the role that anti-democratic foreign governments have played in order to avoid confrontation (in this case with Moscow) is foolish. We have to recognize this attack as such, despite lingering reluctance to do so.

Guardians of the West

Most German lawmakers have until now shied away from calling the current turmoil a “new Cold War,” and there are indeed good reasons not to do so. Still, we should not be fooled by the fact that we are no longer embroiled in the same great-power conflicts of a bygone era. Even if it is not immediately clear what Vladimir Putin’s alternative to liberal democracy actually is, he embodies the forces seeking to dismantle our hard-fought liberties, from gender mainstreaming to gay marriage, multiculturalism, immigration, and perceived political correctness. Putin has in fact fashioned himself to be a guardian of the West, a defender against Islamization, foreign infiltration, and rising feminine influence.

It is no coincidence that Russian broadcasters like RT (formerly Russia Today) and Sputnik have become central sources of information for the new populist movements. Even if these movements do not always align with the Kremlin’s agenda, they offer cheap and easy platforms for propaganda. From the Brexiteers in the UK to Donald Trump in the US, the Five Star movement in Italy, the Front National in France, and the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, populist movements are peddling Kremlin-friendly reports or even replicating Russian propaganda with zeal.

The links between the illiberal movements and their almost symbiotic proximity to the Kremlin are now well documented. The Five Star movement in Italy, for example, has an entire media network that disseminates Kremlin-induced fake news. One platform called TzeTze belongs to a founding member of Five Star and has amassed 1.2 million followers on Facebook alone. It beams out stories like Sputnik’s assertion that refugees and smugglers from North Africa are really financed by the US.

The propaganda does not have to be convincing – it just has to succeed in sowing doubt and calling into question the system of values behind our open societies. And as skepticism towards liberal democracy and the established political order grows, disruptive forces are finding fertile ground. In Germany, a recent poll conducted by the survey institute Forsa with the national weekly DIE ZEIT on August 31, 2016, showed that 31 percent of AfD supporters and 30 percent of left-wing voters trust Vladimir Putin more than Angela Merkel.

Western societies are now turning to the same tools wielded so effectively by Russia. In Peter Pomerantsev’s startling book on Russia’s media landscape, Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: Adventures in Modern Russia, he describes the mechanisms of political technology in a world where it matters little whether something is true or not.

What is true today can be obsolete tomorrow: one day, Putin can claim there are no Russian soldiers in Crimea; the next day, he can casually admit that Russian soldiers had been active on the Black Sea peninsula all along. If the truth is blurred, twisted, and distorted long enough, the standards by which we orient right and wrong disappear. Propaganda does not have to be consistent. As the influential political theorist Hannah Arendt wrote more than sixty years ago, the best subject of totalitarian rule was neither the convinced Nazi nor the convinced communist, but the man who could no longer distinguish between true and false, between facts and fiction.

The “Post-Truth” Era

The relativization of truth is not just a tool employed by Russia. The Oxford Dictionary word of the year in 2016 was “post-truth.” According to an analysis on Buzzfeed, in the last three months of the US election campaign the twenty most influential fake news stories generated more response on Facebook than the twenty most influential real news stories produced by traditional media.

In the lead-up to the Brexit vote, it was the seemingly farcical stories on British payments to Brussels and the economic consequences of leaving the EU that proved more powerful than facts from economic groups or the Bank of England. “People in this country have had enough of experts,” declared conservative Justice Secretary and Brexiteer Michael Gove, when he was questioned on why no economists supported Brexit.

In the US, meanwhile, the Democratic Party’s confidential emails were leaked to the public. Dmitri Alperovitch of the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike warned back in July that the hacker collectives Fancy Bear and Cozy Bear were responsible. Experts said the style and approach showed all the hallmarks of Russian intelligence services.

In September, at the Munich Security Conference’s special Cyber Security Series at Stanford University, US intelligence representatives and cyber experts raised the alarm over the growing influence of foreign intelligence services on American elections. Nearly a month later, the Office of Homeland Security and the CIA announced they were certain that the Russian government were behind the hacks; the scale and sensitivity of the operation indicated involvement at the highest level.

This is not the first attempt to influence public opinion in Western societies. But the ability to disseminate information through social media and online gives illiberal forces new powers and bandwidth. And it comes as social media users are increasingly divided into insular groups that quickly become echo chambers. That trend leads to greater polarization and information tribalism, where each societal group lives its own version of truth and reality. These increasingly isolated groups are especially vulnerable to propaganda and fake news.

That is why protest parties and alternative media gain such traction on social media. With the slogan “We write what others can’t print,” Germany’s far-right magazine Compact has amassed upwards of 90,000 followers on Facebook. The outlet propagates conspiracy theories and stories touting Putin as a champion of balanced dialogue and restraint, unlike the EU.

Whether it’s fake news, leaks, trolls, or automated social media bots, these instruments present a grave challenge to enlightened public debate, the core of a functioning democracy. How do you maintain the principles of balanced, democratic debate when a significant percentage of those taking part are not real people or when they cast doubt on these very principles in the first place?

It Can Happen Here

After the US elections, the German chancellor was celebrated as the “leader of the free world,” and Germany fast became the last bastion of liberal democracy. But German society is not immune to illiberal forces. On the contrary, the fact that Berlin played a central role in rebuking Russian aggression in Ukraine makes it a target for propaganda and disinformation campaigns, especially from those who reject sanctions and strive to protect Russia’s “sphere of influence” in Eastern Europe. The chancellor has already expressed concern that Russia might interfere in this year’s election campaign. And the head of Germany’s intelligence agency, Bruno Kahl, warned, “This kind of pressure on public discourse and on democracy is unacceptable.”

With pressure mounting, the building blocks of our open society must now actively fight to safeguard it. Government institutions have to take every possible step to protect our hardware and shield constitutional bodies from cyberattacks. But the task of maintaining our software is up to society.

Lawmakers and stakeholders need to publicly speak out about our democracy and the myriad ways it can be influenced. They should open up access to free pools of information as a way to discredit fake news campaigns and supplement the efforts of virus scanners that track and report false information – like the European External Action Service (EEAS), which reports on Russian disinformation twice a week. The German government should also consider how to curb websites that regularly violate constitutional laws. But in a society that nourishes and protects freedom of opinion, this will be difficult.

It would be especially helpful to employ independent, non-governmental organizations to monitor the quality and credibility of media coverage, even producing a blacklist with particularly egregious transgressions. Companies that choose to advertise on platforms that consistently disseminate disinformation or propaganda should face consequences. And lawmakers themselves should refuse interviews with questionable sites so as not to legitimize them.

The challenge will be great for television, radio and other news outlets. Populists have revived the Nazi-era smear “Lügenpresse,” or lying press, to blast what they see as biased mainstream media. But it is precisely these established outlets that play such a central role in educating society on how to parse disinformation and fake news.

German media are fortunately far less polarized than in the US; a 2014 poll from the Pew Research Center revealed that 47 percent of conservative American voters turn to Fox News as their chief source of information. Germany’s public broadcasters and national dailies still reach a broad spectrum. But established media have come up short on two fronts.

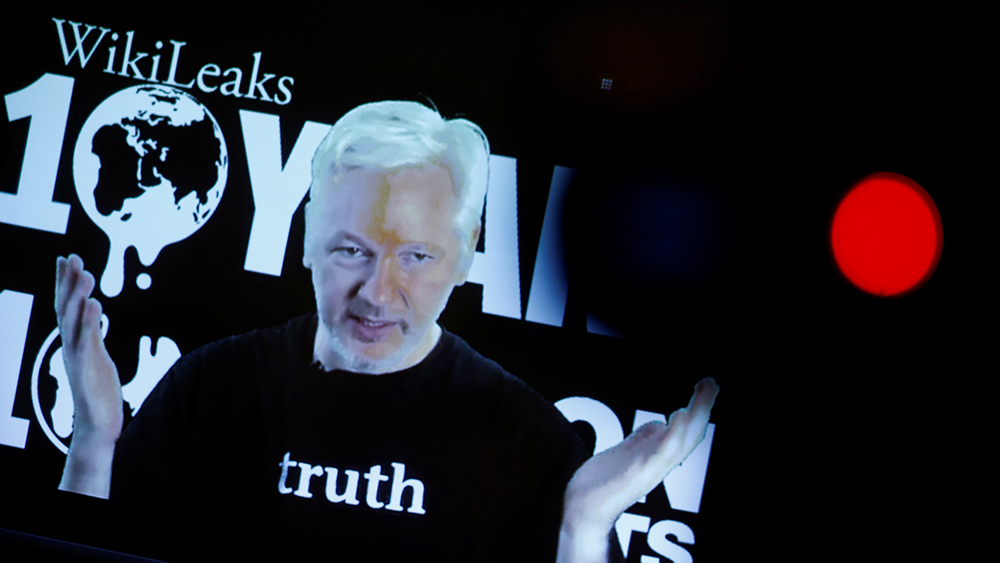

First, several outlets readily republish large leaks without taking a critical look at who or what is behind them and without differentiating between what is authentic and what is fabricated. During the Cold War, the Stasi and the KGB often tried to leak compromised material to Western media, but they wouldn’t make such information public. Now, close ties between intelligence services and platforms like WikiLeaks have renewed a debate over the ethics of leaks, and journalists can’t afford to ignore the discussion.

Second, there is a growing trend toward feigned objectivity in various talk shows and even mainstream news. Russian propaganda is reproduced without context or challenge. Germany’s popular political talk shows feature guests who are presented as independent experts but clearly hawk the Kremlin’s line. If their statements are not challenged or even disproved, the viewer is left with a sliver of doubt and the impression that the truth is somewhere in the middle.

Back to the Facts

That is not to say that we should not challenge the West’s policy on Russia. We can and must examine whether the EU’s sanctions, for example, are actually counterproductive. And an open society must tolerate the wrath of its critics (as long as they remain within the bounds of the law). We need to engage the populists in our discourse, not shut them out. But we also cannot tolerate half-truths or false information, nor can we accept foreign propaganda. In the end, there is nothing more critical than our liberal democracy itself. And it cannot survive without a fact-based, open debate.

Read more in the Berlin Policy Journal App – January/February 2017 issue.