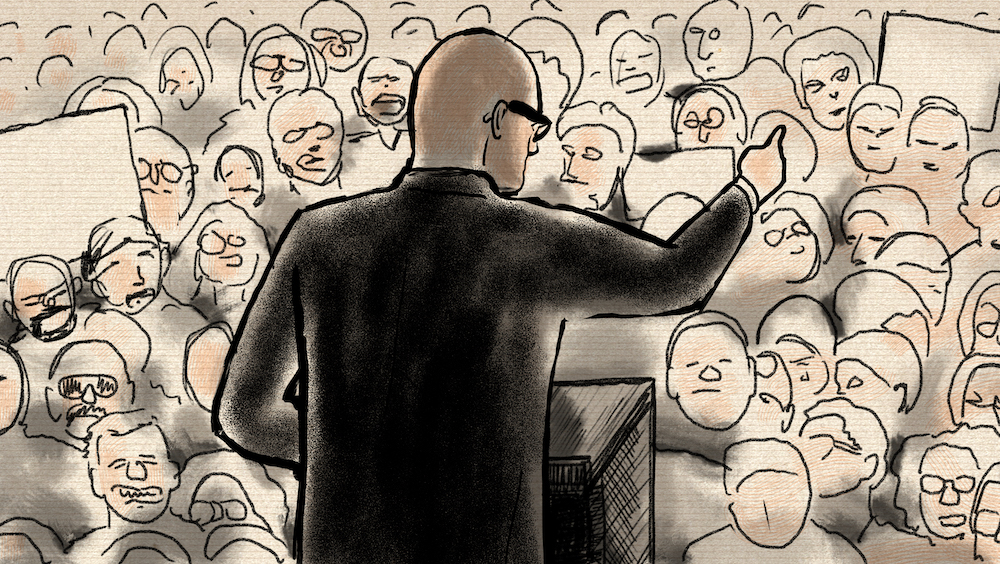

There are fears that the growing populist forces on the right and left are paving the way for authoritarianism. Yet those same forces can also be seen as a necessary correction to a failing system.

In an atmosphere of crisis such as the one we’re currently enduring, there’s no easier way to dismiss your political opponents—especially if you’re in a rush and you need to find the killer stroke in an internet-based brawl—than to call them a “populist.”

It makes things so easy because everyone knows what the word implies, if not what it actually means. It suggests a sort of childish disposition: a populist insists on their moral rightness, they’re not able to have a rational argument, they have no patience for liberal compromise, and—here’s the main thing—they are easily seduced by an “elites” versus “people” view of the world.

That last point is the key element of what has become the textbook definition of the term “populism,” developed by Dutch academic Cas Mudde. In his 2004 paper, the “Populist Zeitgeist,” he defined populism as “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite,’ and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” This sharpened the focus of the academic understanding of populism, and though it was apparently little read on publication, it hit its moment emphatically a few years ago.

Mudde’s description of populism chimed particularly well with the global political upheaval that began circa 2014: new parties were suddenly undermining institutions that held the world together, winning elections by exploiting a lack of trust in the mainstream. These insurgents broke the grip of old parties, and they did it by pitting an indivisible “will of the people” against a rich urban elite.

Mudde’s definition proved even more useful because it talked about populism as something more than a strategy but less than a proper ideology. He explained that populism isn’t just rabble-rousing demagoguery—it is a kind of parasite, a simple set of ideas that can feed off either left or right-wing politics. This incidentally turned out to a good explanation for why the term has proved so difficult to define: populism is a boneless, shape-shifting creature, clinging onto other ideologies.

The theory proved a handy intellectual way of explaining the old “horseshoe” cliché about how left and right-wing extremists end up resembling each other. As a result, the doors were opened to countless alarming parallels with the rise of fascism and communism in the early 20th century, which brought with them the sense that a century-long cycle had come round again, and the would-be dictators were on the rise.

Creeping In From the Edges

To bring the point home, Mudde’s definition was adopted by The Guardian in its “new populism” section, which has been tracking the growing success of populist politics all over the world. In the past few months, the United Kingdom’s leading liberal newspaper published two major studies it had commissioned from a team of political scientists across dozens of countries, which came to two conclusions: firstly, that populist parties had tripled their support in Europe in the last twenty years, and secondly, that in the same period there had been a corresponding surge in populist rhetoric from political leaders.

This second survey showed “empirically,” Mudde wrote in the same newspaper in March, “what many have asserted and felt”: that populism was creeping from the edges into the middle. Political leaders from nominally centrist old parties were getting spooked by populist successes, and so “more and more mainstream politicians are using ‘pro-people’ and/or ‘anti-elite’ rhetoric to win voters—in part to fight off electoral challenges from true populist actors.”

The consequence is that populism appears to be a threat to democracy itself: the people’s gateway opiate to full-blown authoritarianism. That is a story told by many new popular politics books, such as How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt.

It’s hard to argue against this reading, given the developments of the last few years across Europe. That populism is a direct threat to the democratic order of the European Union was shown by the UK’s Brexit referendum in 2016, when the Leave campaign shamelessly employed anti-elite rhetoric to make its case.

And for evidence that populists attack democratic institutions as soon as they gain power, one need only look as far as Poland, where the European Court of Justice has had to intervene to stop the ruling Law and Justice party (PiS) loading the supreme court with friendly judges. Or one could point at Hungary, whose right-wing Fidesz-led government has been sanctioned by the EU for undermining media plurality and suppressing civil society.

Populism Is Just Politics

But there’s a danger that this narrative widens the definition of populism so far it becomes meaningless: simply conflating populism with the ideologies it might enable doesn’t really help us to understand much. It certainly doesn’t help understand the more profound reasons why our democracy is under threat.

As political scientist Jason Frank of Cornell University wrote in the Boston Review last year, crying populist only perpetuates confusion over the nature of new movements. “Authoritarian attempts to centralize and expand the state’s executive power and wield it against ‘enemies of the people’—however defined by Trump, Erdoğan, Orbán, and others—should never be equated with the radically democratic institutional experimentalism of Podemos (in Spain) or the Farmers’ Alliance (in 1880s USA),” Frank argued.

Not only that, making populism the preserve of the radicals obscures the fact that apparently rational centrist politicians are just as capable of making blatantly populist moves—like Angela Merkel’s conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU) regularly announcing tax cuts just before elections.

The Mudde definition of populism has been questioned by other academics too. Chantal Mouffe of the University of Westminster in London is among those to argue that what gets dismissed as populism is actually just a necessary correction to a system that has seized up. As center-right and center-left government parties fused into a kind of management board whose main job is to oversee a neoliberal debt-based economy, Mouffe argued in The Guardian, something had to give when evidence mounted that that system was failing. No status quo lasts forever.

For Mouffe and others, the rise of populism is actually the sight of politics being reacquainted with its life-blood: a basic conflict about how society should be organized. In fact, one could conclude that the sooner the old centrist politicians start joining that debate, rather than desperately painting the new parties on the right and left as extremist threats, the more likely they will be to survive.