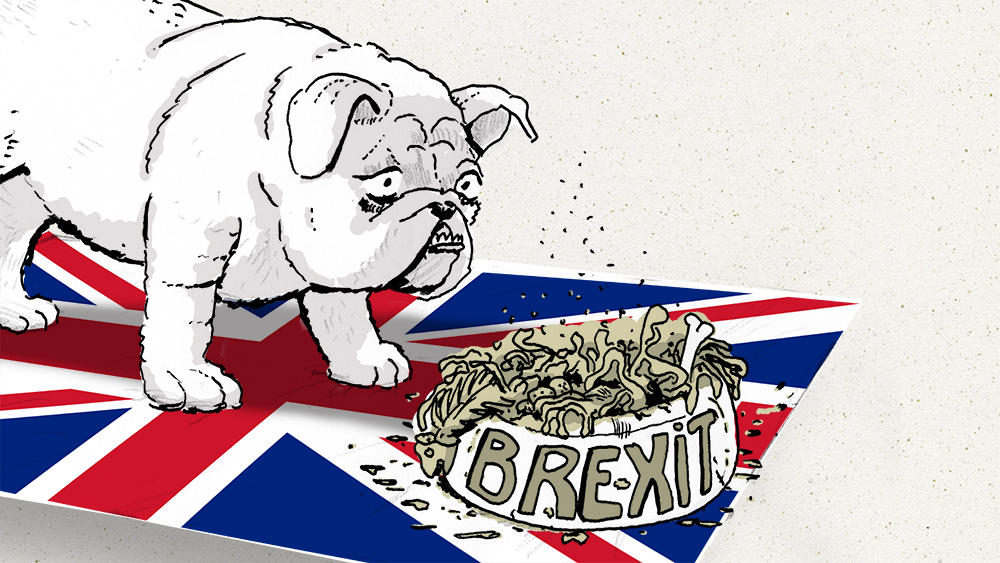

It began life as a variant of Grexit. Fours years on and a referendum later, the terms is still devoid of any meaning beyond “somehow” leaving the European Union. It’s a dog’s dinner.

“Brexit means Brexit.” No other sentence has been so often repeated in British politics in recent months. And no other sentence has been so meaningless. Its value has now been so debased that even government ministers privately recognize it has no value other than as shorthand for “we don’t know what the hell we’re doing.”

The term Brexit, freshly minted 2016 “word of the year” by dictionary publishers Collins, first appeared four years ago as a British variant of Grexit – the difference being that where Grexit referred to the specific possibility of Greece having to leave the euro, Brexit was a catch-all term for Britain leaving the EU. However, it wasn’t until just before the general election campaign of 2015, when then Prime Minister David Cameron had promised a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU, that Brexit entered the mainstream.

Politicians came to adopt the term Brexit specifically because it described everything and nothing. During the EU referendum campaign, the debate became so diminished that no one ever thought to really enquire what Brexit would mean: principally because no one – not even those supporting the Vote Leave campaign – had ever seriously entertained the idea that Britain might actually vote to leave the EU. Why go to all the hassle of trying to define something that would never happen and would soon be forgotten?

The absurdity of the situation only really began to become clear in the last few weeks of the campaign when the opinion polls indicated that the leave side stood a reasonable chance of winning, at which point both sides went into meltdown. The government – and opposition – backed Vote Remain campaign refused to engage with the possible aftermath. Brexit was some kind of disastrous fugue state: something akin to a diagnosis of terminal cancer.

Vote Leave was equally unwilling to give the realities of Brexit any great thought. Just shouting, “Brexit is going to be great!” seemed to be playing out perfectly well as it was in many areas of the country, so why spoil things by going into details? In one of the most breathtaking pieces of cheek in an already cynical campaign, Vote Leave even insisted it wasn’t their responsibility to tell the country what Brexit would actually mean in practical terms and it was up to the government to explain what would happen next.

On the morning of June 24, the day after the referendum result, it became clear that what Brexit actually meant was chaos. After promising the country that he would stay on to manage Britain’s departure from the EU if the vote was to go against him, the first thing David Cameron did was to announce his resignation. Hours later, Michael Gove and Boris Johnson, two of the leading architects of the Vote Leave campaign, appeared before the TV cameras looking like men who had just come down off a bad trip only to discover that they had murdered several of their closest friends. Throughout the campaign, they had driven round the country in a bus with a slogan across the side promising to give Britain’s weekly contribution to the EU budget of £350m directly to the National Health Service, knowning this was totally undeliverable – partly because Britain’s weekly EU contribution was nowhere near £350m and partly because no choice is ever that binary.

As it happened, neither Johnson nor Gove were called to account as the two men fell out within a week of the Brexit vote. The Conservative party elected Theresa May, a politician who had campaigned – if ever so quietly – for the remain side. In the post-truth world of British politics in 2016, Brexit meant a remain campaigner heading the negotiations for Britain to leave the EU.

The Cunning Plan Is to Have No Cunning Plan

May’s first response was to repeatedly say, “Brexit means Brexit,” as if by so doing the country would believe she knew what she was doing. Once it became apparent she didn’t, she announced she wasn’t going to give a running commentary. Her cunning plan would be to have no cunning plan, and the Brexit that we ended up with would have been the one she had always intended to get.

The reality was that no one really knew what was and wasn’t possible. Was Britain hoping to retain access to the single market and membership of the customs union? This became known as the “soft Brexit.” A Brexit that would feel like Britain were still in the EU even if it weren’t. For others, the ability to restrict freedom of movement and to regain control of Britain’s borders was the principal concern. As this was incompatible with remaining in the single market, it became known as the “hard Brexit.”

Needless to say there were any number of other Brexit permutations along the way: softish and hardish Brexits, none of which anyone appeared to be able to completely spell out. The more politicians tried to explain Brexit the more that definition eluded them. Bizarrely, the hardest Brexiteers – the ones who were most keen on the right of the British parliament to make its own laws – were the ones most keen to exclude parliament from having any say in the exact nature of Brexit, because most MPs in the House of Commons had supported the remain side. Go figure.

With no agreement on what even a hard or soft Brexit might look like, politicians began to subdivide its meaning still further. Some feared a Bankers’ Brexit – one which favored the financial service industries and no one else – and demanded a People’s Brexit instead. Before long the inevitable happened and the leader of the Conservative party in Wales said, “Brexit means breakfast.”

Before long that too had caught on, and John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor referred to breakfast three times in a single speech on Brexit. He was almost right. Right now Brexit doesn’t mean breakfast. Brexit means dinner. A dog’s dinner.