As the sober National Interest warns that America and Russia are “stumbling to war,” roughly four Western scenarios compete to explain where we stand in the year-old Ukraine crisis. Let’s call them the McCain, Mearsheimer, Motyl, and Merkel theses of, respectively, Russian aggression, Russian hegemonic privilege, Russian decline, and Russian paranoia. (Part 1 of 2)

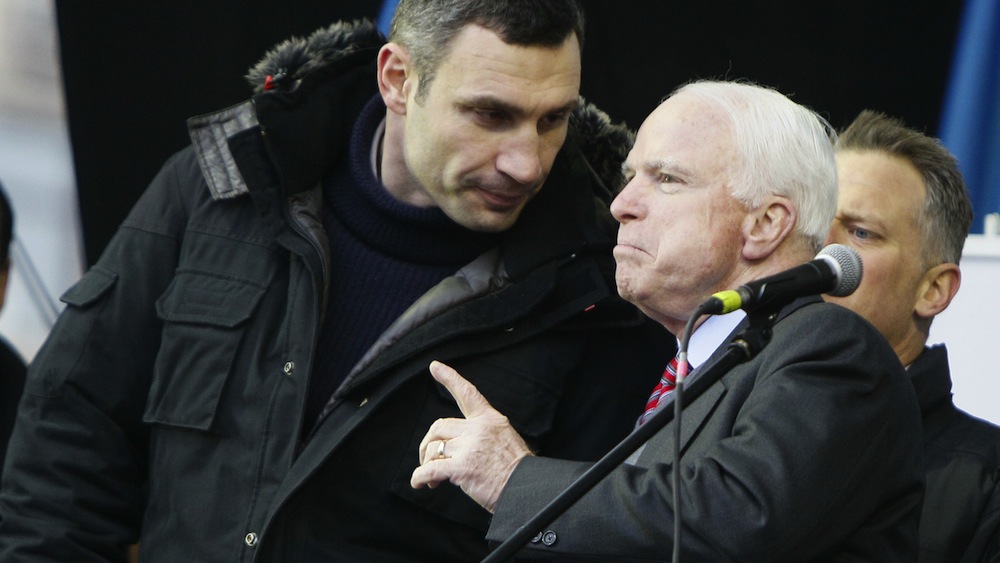

US Senator John McCain sees Russia’s undeclared war on Ukraine as an epic (and hotter) re-run of the Soviet-American Cold War that the wimpish United States is losing to Putin’s military juggernaut and superior political will. University of Chicago purist realist John Mearsheimer, by contrast, regards Russia as behaving normally for a great power in invading a smaller neighbor, annexing Crimea, and then stoking secession in eastern Ukraine through military coercion and patronage.

Rutgers political scientist Alexander Motyl, on the other hand, contends that Russian President Vladimir Putin is losing the contest in the long run and that Ukraine finally holds the initiative, despite the Russians’ overwhelming superiority on the battlefield. And German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who leads the West’s diplomatic efforts to de-escalate the violence in Ukraine, argues – to put it more bluntly than she herself does – that it is Putin’s post-empire paranoia that makes the current state of play so dangerous.

The difference matters: the four premises imply very different Western responses. In essence, the McCain thesis assumes that the ongoing Russian military buildup in eastern Ukraine is laying the groundwork for Moscow to overturn the present fragile truce and launch a fresh offensive in Ukrainian “Novorossiya” in the next few weeks, and that there is no non-military solution to Russia’s regressive violation of Europe’s seven-decade taboo on forcible seizure of a neighbor’s territory. The West must therefore avoid appeasing Putin as it once appeased Hitler, and instead give Ukraine lethal weapons to defend itself while calling Putin’s bluff that he would trump any Western escalation all the way up to the nuclear level.. For his part, John Mearsheimer blames the West itself for provoking the Russian bear, and counsels Washington to simply defer to Moscow in its sphere of influence.

Motyl maintains that Kiev should cede to Moscow the half of the Donbass that is already controlled by Ukrainian rebels and Russian soldiers, defend the remainder of Ukraine and make it a showcase of economic and democratic development, and deter further Russian encroachment on Ukrainian territory. Deterrence could be achieved, he believes, through the cumulative impact of the West’s financial sanctions, rising Russian casualties, and Russian generals’ worry that any escalation of the army’s mission to occupying Ukrainian territory against probable partisan guerrillas would overstretch its capabilities. At this point, he posits, it is Moscow rather than Kiev that would lose if there is a stalemate.

Finally, the pragmatic Chancellor Merkel insists that there is no possible military solution given the West’s weak geopolitical position in Russia’s backyard. She focuses instead on deescalating the level of violence in Ukraine to a semi-stable level and relying on the long-term policy of containment that won the first Cold War.

This blog explores the McCain and Mearsheimer theses. A second post will examine the Motyl and Merkel variants.

The McCain View

It became clear how sharply Senator McCain’s view diverged from Merkel’s last February on the sidelines of the blue-ribbon Munich Security Conference. In a private meeting between German officials and American politicians, he lambasted the chancellor (and President Barack Obama) for not sending lethal weapons to Ukraine, and compared the European pursuit of peace talks with Putin to Neville Chamberlain’s infamous appeasement of Hitler in 1938. Shortly thereafter, in unusually caustic criticism of an allied leader, McCain complained to a German TV interviewer that one could think Merkel “either had no idea that people in Ukraine were being butchered, or was indifferent to it.”

Former NATO commander Wesley Clark, the most prominent spokesman for the McCain approach today, recently made the case that delivering weapons was the only course that could deter further “military adventurism” by Putin in Ukraine. He said that Ukrainian forces, although they are vastly inferior to the Russian military machine in manpower and weapons, are ready to fight, and even came close to defeating the Russian-led secessionists in eastern Ukraine last August. Ever since, the Russians have been augmenting their already superior arsenal in the area despite making tactical withdrawals under the truces that Merkel negotiated with Putin in September and February. Moscow has used the barely monitored ceasefires to infiltrate ever more tanks, rocket launchers, and drones into the Donbas, amass some 50,000 troops on the Russian side of the Russian-controlled border, and fire artillery from Russian soil onto Ukrainian strongpoints. Last January Moscow also sent “rotating commanders” into the Donbas to lead the secessionists’ renewed surge there and push the truce line westward along the 400-kilometer front.

Neither financial sanctions nor diplomacy can stop “the Russian war plan,” Clark argued. Therefore, Ukrainians – who are fighting “the battle of Western civilization” for all of us – should be provided with the lethal defensive weapons that would enable them to repel “the next wave of the attack” that Clark expects the Russians to mount in the next few weeks. Specifically, he wants the West to equip the Ukrainians immediately with portable Javelin fire-and-forget anti-tank missiles.

The Mearsheimer View

Mearsheimer also perceives the Ukraine crisis in black and white; however, he flips the colors by declaring that “the United States and its European allies share most of the responsibility for the crisis.” The trigger was not Russian actions, but NATO enlargement in the past quarter century as “the central element of a larger strategy to move Ukraine out of Russia’s orbit and integrate it into the West.” American and European leaders “blundered in attempting to turn Ukraine into a Western stronghold on Russia’s border.” This threatened Russia’s “core strategic interests.” Putin was understandably displeased, which he demonstrated in 2008 by invading NATO applicant Georgia and in 2014 by seizing Crimea. The Russian president feared that Crimea “would host a NATO naval base,” and he therefore began working “to destabilize Ukraine until it abandoned its efforts to join the West.”

“The EU, too, has been marching eastward,” Mearsheimer continues. “In the eyes of Russian leaders, EU expansion is a stalking horse for NATO expansion.” Moreover, “[T]he West’s final tool for peeling Kiev away from Moscow has been its effort to spread Western values and promote democracy in Ukraine and other post-Soviet states, a plan that often entails funding pro-Western individuals and organizations” like the pro-Europe demonstrations by Ukrainian activists in the center of Kiev at the end of 2013 and beginning of 2014. “[T]he West’s triple package of policies – NATO enlargement, EU expansion, and democracy promotion – added fuel to a fire waiting to ignite.” It was therefore understandable that Putin would not tolerate more Western meddling in the “buffer state” that has long been the gateway to Russia, just as Washington would not tolerate a Chinese attempt to incorporate Canada or Mexico into a military alliance.

Mearsheimer does agree with McCain in dismissing financial sanctions as ineffective. But his policy prescription is diametrically opposed to McCain’s: “The United States and its allies should abandon their plan to westernize Ukraine and instead aim to make it a neutral buffer between NATO and Russia … And the West should considerably limit its social-engineering efforts inside Ukraine.” The super-realist rejects any protest that the independent state of Ukraine should be free to determine its own future as unrealistic. “The sad truth is that might often makes right when great-power politics are at play.” Since Ukraine is not a vital interest for the United States, Washington should simply reject Kiev’s clamor to join the European Union and NATO and not let Ukrainian wishes “put Russia and the West on a collision course.”