The refugee crisis in Europe is a modern tragedy playing out in three acts: the problem has been introduced, and now the main characters are locked in confrontation. But the conclusion remains uncertain.

Germany has certainly stepped up its role in the migration and refugee policy world over the past few months, pushing for policy measures in the EU that would have been out of the question just a year ago. In fact, Germany’s transformation into a leader in the migration and refugee crisis follows the structure of a classical three-act theater play: we saw the protagonists introduced, now we are watching them as they are confronted – and transformed – by the scope of the problem. We find ourselves at the beginning of act three, watching Angela Merkel, embodying Germany, learning important lessons as she juggles national and international adversaries and interests, absorbing calls for upper limits for asylum seekers within Germany while maintaining a “we can manage this” approach to this historic test of her leadership.But before we get to the conclusion, we have to begin at the beginning.

Act One: A New Actor Debuts

For years, Germany was more or less absent on migration policy at the EU level. Berlin repeatedly blocked any meaningful reform of the Dublin system, which requires that asylum seekers make their claims in the first EU country they enter, placing most of the burden on border states. Shielded by a ring of buffer states, Germany quietly relaxed backstage while others, like Italy and Greece, were front and center, asking for support in managing increasing numbers of migrants and asylum seekers.

Then last year, the number of people making their way north from Italy and Greece – mostly undocumented – began to surge. While other countries were receiving more migrants and asylum seekers per capita, the increased number of people arriving in Germany put a considerable strain on unprepared German cities and communities. This strain ultimately pushed Merkel to step out of the background and onto the European stage as she realized that Germany could not manage the increasing numbers on its own and needed European and international actors to help. It was not solidarity with Italy or Greece, nor a historic obligation to offset the atrocities of World War II, nor any other higher motive that compelled the shift; it was simple self-interest, combined with the inconveniently late realization that the Dublin system really was in need of reform, and that the war in Syria was no closer to ending.

Thus it was Berlin’s turn to call for European solidarity, backing the Commission’s relocation plans, and pushing for a permanent quota among member states. At the same time, Germany was applauded internationally for taking up to 800,000 migrants and asylum seekers. Never mind that Germany did not want to take up all these people, and had simply corrected its estimates to pragmatically prepare for the increase – an image of Germany’s openness was born.

…

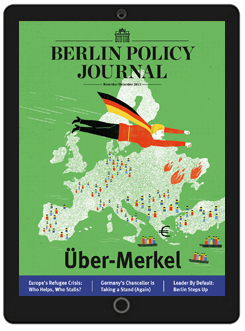

Read the complete article in the Berlin Policy Journal App – November/December 2015 issue.