The refugees entering the EU are changing the countries that accept them – and those that do not. One of the Eastern European refuseniks, Poland, has been forced to confront uncomfortable questions.

Overcrowded railway stations, overwhelmed local authorities, hastily built tent camps – all these pictures haunting the media came from Germany, Hungary, and Greece, but not Poland, which, until November 2015 virtually no refugees have entered. Only 6700 asylum applications were submitted here in the first eight months of the year, mostly by Chechens, Ukrainians, and Georgians, and only 471 of them (including 153 Syrians and 37 Iraqis) were granted refugee status. A wave of immigration predicted to arrive from Ukraine due to the ongoing conflict there has thus far not materialized.And yet, in one respect the refugee crisis has hit Poland just as much as the countries already coping with the influx of migrants: it set off a heated public debate touching upon the most sensitive aspects of Polish political life. Not surprisingly, Polish refugee policy was a controversial and divisive issue in the campaign before the general elections on October 25, an election which brought about – after eight years of the liberal Civic Platform party being at the helm – a change of government, with the national-conservative opposition Law and Justice party receiving its best-ever result of 39 percent of votes. But the election does not fully account for the depth and magnitude of the challenges posed by the still virtual migration problem in Poland.

In fact, the question of if and how Poland should take responsibility in the EU for dealing with refugees is forcing Polish society to confront long overdue questions about identity, community, and foreign policy. The refugee crisis has arguably started changing Poland even before the first migrants arrive in the country.

“They are not refugees, they are aggressors,” screams the front page of the leading conservative weekly Do Rzeczy, calling upon the government to “close Poland’s borders.” The new Polish Prime Minister Beata Szydło during the campaign was quoted saying that “instead of Arabs and Negros, Poland should first invite Poles from the East [Polish emigrants to Kazakhstan and other post-Soviet republics].” On the other hand, the liberal media, most notably the largest daily newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, have been instrumental in pushing the public debate in another direction entirely. That said, its call to support a demonstration at the end of September in Warsaw called “Refugees are welcome” attracted under 2000 people. The opposing nationalist demonstration was at least four times larger.

Deep-Rooted Concerns

Concerns about immigration and, more generally, encountering the “other” are deeply rooted in Poland, as they are in other Central and Eastern European countries. In a striking contrast to Western Europe, this region’s experience with multiculturalism (understood not as a policy but a social reality) is very limited, maybe even non-existent. The memory of Poland between the 16th and 18th century as a multi-ethnic and multi-religious empire has waned, and fails today to act as a source of identity for the modern nation-state. Prewar Poland was not an immigrant society, and its multicultural character was in no small part to do with the large Jewish (as well as Ukrainian and German) populations, which were long-established minorities in the territories that made up the Polish state at the time.

Today immigrants constitute just 0.3 percent of the country’s population. Accordingly, integration and refugee policies have ranked low on the political agenda for the last 25 years. Poland’s acceptance of around 80,000 Chechen refugees in the 1990s (who either assimilated quickly or left the country soon after) has not changed public perception of immigration or made it a matter of public concern. The refugee crisis and pressure from European partners to accept a fair share of responsibility found Polish society and the state wrong-footed, both mentally and politically. …

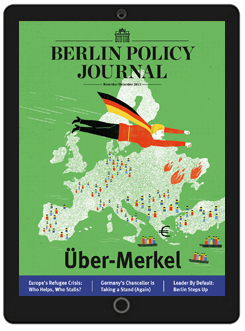

Read the complete article in the Berlin Policy Journal App – November/December 2015 issue.