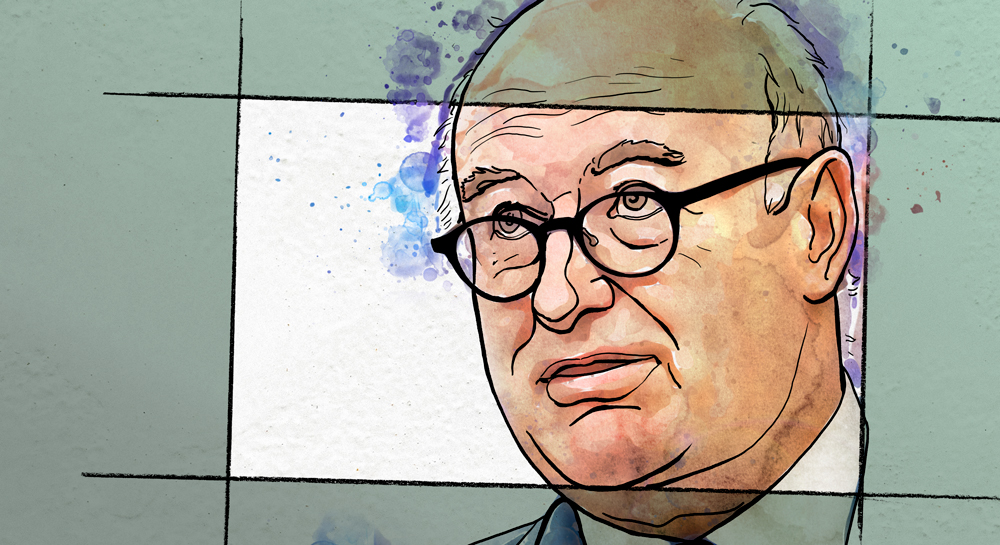

Known as a tough negotiator, the EU’s future trade commissioner is used to being unpopular. The Irishman has his work cut out safeguarding Europe’s interests around the world―and navigating Brexit.

On the morning Phil Hogan was nominated as the EU’s next trade commissioner, he told Ireland’s public broadcaster RTÉ his priority was “to get Mr. Trump to see the error of his ways.” The US president should abandon his “reckless behavior” when it came to China and the EU.

His remarks did not go unnoticed. EU diplomats in Washington reported back immediately that there was outrage in the White House. “We were told it was fortunate that John Bolton [the hawkish former National Security Adviser] had just been fired the same day,” recalls a close aide, “or that the president himself might have tweeted his reaction.”

Trump didn’t tweet, but his ambassador Gordon Sondland delivered the message to Politico, accusing Hogan of a “belligerence” that would lead to an impasse between the EU and US. “Then people start to do things that you don’t want them to do.”

It was a combative start, confirming Hogan’s reputation as a political bruiser with a sharp tongue. However, many in Brussels felt Hogan was right. The US was waiting for the new EU executive to take office, and Hogan was reminding the world who the new interlocutor would be.

His timing, however, may have been unfortunate. The next day, the WTO ruled in a decades-old dispute with Boeing that Europe had granted illegal subsidies to Airbus. As a result, Trump was expected to announce up to $10 billion in tariffs on European products.

Making the Strategic Case for Trade

All told, the 59-year-old, hailed by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen as a “brilliant” and “firm” negotiator, could not have taken up his post at a more turbulent time. The United States and China are locked in a trade war, China is accused of wholesale technology theft, Trump is threatening more tariffs on European goods, and Brexit is sapping the EU’s energy.

European efforts to sail above the turbulence as the self-identified defender of the rules-based global order are limited. “So far, the EU has benefitted from the turmoil created by Trump’s trade war,” says Sam Lowe, a research fellow with the Center for European Reform (CER), “which provided the political impetus to conclude trade agreements with Japan, Canada, Mexico, Singapore, and Vietnam; but the waters ahead look choppy.

“Phil Hogan will need to make the strategic case for a resilient trade policy. But he will face a European Parliament looking for greater reassurance that the EU’s trade policy complements its environmental ambitions, and an inwardly focused European agriculture lobby.”

That lobby has been up in arms over Hogan’s role in negotiating the EU-Mercosur trade agreement as agriculture commissioner. South American farmers will enjoy increased access to the EU, but the access for beef―an annual quota of 99,000 tonnes―has enraged farmers, not least in Hogan’s home country.

The Irish Farmers Association claims Mercosur beef will cost European farmers €5 billion annually, compounded by a lack of traceability, food safety, animal health, and environmental controls. Hogan hit back: “There will be no product that will arrive in the EU from the Mercosur countries without complying with existing EU food safety standards.”

The Road from Kilkenny

Hogan was born just outside Kilkenny in south-east Ireland to a small-holder farming family. He followed his father into politics and won the parliamentary seat for the center-right Fine Gael party that had always eluded his father.

He was a junior finance minister in 1994 in the Fine Gael-Labour coalition, but was forced to resign when a staff member accidentally leaked details of the annual budget. Observers say Hogan nursed a longstanding grievance at his premature fall and was determined to make a return to ministerial politics.

It started by being appointed party chairman. “This put him in a position of extraordinary influence,” says a longstanding associate. “He got to know the organization intimately. He became director of elections, selecting candidates, placing candidates.”

Hogan honed his skills as a ruthless political operator. When in 2010 a minister attempted a coup against Enda Kenny, the party leader turned to his longtime friend Hogan for advice. Hogan told him to sack the entire shadow front bench.

Kenny promptly did so the next morning. While 15 rebel MPs assembled in front of the Irish Parliament to declare the revolt, Hogan rounded up 40 loyalists and sent them to the same spot. The coup was over as soon as it had begun.

Happily Unpopular

But Hogan soon made a bigger impact on Irish politics. In 2011, Fine Gael swept to power following the collapse of the Irish economy due to the banking and sovereign debt crisis. Hogan was appointed environment minister.

Under the advice of the EU-IMF troika administering the bailout, the government established a new state utility, under Hogan’s direction, which would introduce water charges in Ireland for the first time.

Hogan insisted the new charges would cost as little as €2 per week, but there was a backlash when he warned that those who did not pay would see their water supply “turned down to a trickle for basic human health reasons.” To many reeling from the austerity of the bailout years, this was callous in the extreme.

The theory is that Hogan took on the poisoned chalice of water charges because he knew Kenny would appoint him Ireland’s Commissioner three years later. “There was a neat choreography,” says one source close to Hogan. “Kenny needed someone with balls to do the job, and who was also happy to be unpopular because they weren’t going to be around.”

Journalist Michael Brennan, who has just published a book on the affair, In Deep Water, says, “It was one thing to take a bullet for other people. It’s another when you’re casual about doing it, knowing you have the job in Brussels sown up. He had to convince people this was a charge worth paying and he failed to do that. Within months of his going to Brussels, they had torn up the Hogan plan and came up with a very different approach.”

Negotiating Brexit

But Hogan had other things on his mind when he arrived in Brussels. Within two years the United Kingdom launched its Brexit referendum. Hogan was the only senior EU official given a license to make the case to remain, travelling to farm meetings and agricultural shows around the UK.

“He spoke very well about the importance of the EU for farmers,” recalls a senior European Commission official, “both in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and in trading opportunities. But he spoke as an Irishman as well, in terms of keeping the UK and Ireland together in the EU. He made a real contribution. He might even have swung quite a number of votes.”

That Hogan, a searing critic of Brexit, will be Brussels’ top negotiator when the future EU-UK trade talks start has not been lost on Boris Johnson’s government.

Going the Extra Mile

He is described as a tough negotiator. Despite the hostility of the farming lobby, Hogan’s supporters say he went the extra mile to limit the access of South American beef, holding up the Mercosur talks and irritating member states keen to get the deal over the line.

“Mercosur would not have been done without him,” says one EU source. “He doesn’t hold back in protecting Europe’s defensive interests. Farming often ends up as one of the final issues, and depending on your desire to close a deal for the sake of it, people can be more amenable at the last minute. He would step in and say, we won’t give on that.”

Hogan will have his work cut out for him. He is said to have a reasonable relationship with US Trade Secretary Robert Lighthizer dating back to when they negotiated the EU-US hormone-free beef deal. But he will have to tread carefully when it comes to the problem of how to resolve disputes between WTO members. The US has declined to appoint judges to the Appellate Court until the matter is resolved, but has been slow to suggest solutions.

The EU and Canada are working on a mechanism that would bypass the WTO, but a broader framework will be needed to uphold the multilateral rules-based order the EU wants to spearhead.

Lads, Give Us Five Minutes

“Bridge building will be the immediate challenge for Hogan,” says Peter Ungphakorn, a former senior WTO official. “If WTO members feel the US is undermining multilateralism, some kind of alliance could be forged between the EU and China to break this. That is definitely a possibility.”

That will require the ability not just to reconcile the interests of the US and China power giants, but to understand the nuances of diplomacy.

Hogan, who enjoys life in Brussels and can often be seen in one or two of the city’s fabled Irish pubs to watch rugby or Gaelic football, has, say his aides, the skills needed, including for one-on-one encounters.

“I’ve seen him in various places where there are two delegations,” says one aide, “and he’ll say, ‘You might give us five minutes, lads,’ and we’d leave. You’d be amazed at what can happen between two politicians in five minutes.”