No other challenge facing German politics and industry is harder to discuss frankly than how to handle China. Why is this so? And can it be changed?

Let’s start with a thought experiment: Imagine you work for a German company, university or government agency, and you’re flying to the United States for a business trip. There you meet American colleagues, and after the official work is done you go out to eat together. You’re talking about your families and recent holidays, and eventually the conversation lands on current politics: on Donald Trump’s latest Twitter thunderstorm and the support he gets from Fox News. On the situation at the Mexican border, where human rights activists are arguing with the authorities about a humane way of dealing with migrants. On the deep division between the political camps and the outlook for the coming elections. Can you imagine such a conversation with American colleagues? Probably.

And now imagine the same situation in China. You are on a business trip in Beijing or Shanghai. You meet Chinese colleagues, and after the official conversations you go to dinner. You chat about this and that and eventually, of course, also about current politics: about Xi Jinping, around whom the state broadcaster CCTV is building up a Mao-like cult of personality and whose words of wisdom are the subject of a mandatory learning app. About the internment of Uighurs in the western province of Xinjiang, which human rights activists condemn. About the protests in Hong Kong and the question of who might become China’s next head of state. Can you imagine having such a conversation with to your Chinese colleagues? Probably not. And that’s a problem.

The Things You Can’t Talk About

It is harder to speak frankly about China than about any other major topic of our time. The People’s Republic and the United States are the two formative global powers of our time. We have important relationships with both of them; neither one is easy these days. But our discussions with and about China differ from those with and about the US in a fundamental way: with Americans, we can talk about anything; with Chinese, we can’t talk so readily about a lot of things. Even when we are among ourselves, we often act differently—because Beijing could be listening. And when you can’t speak openly about something, it’s hard to reach a consensus and settle on a functional strategy.

When German top politicians go to China, commentators always ask whether they use “the right tone.” What do they say in public? What about behind locked doors? And what, in the best case, not at all? There’s no other big country that attracts the same amount of attention from commentators when it comes to this issue—not even Donald Trump’s America. There, too, diplomats do their best to skillfully handle the unpredictable president. But otherwise one can have open and “grown-up” conversations with American counterparts.

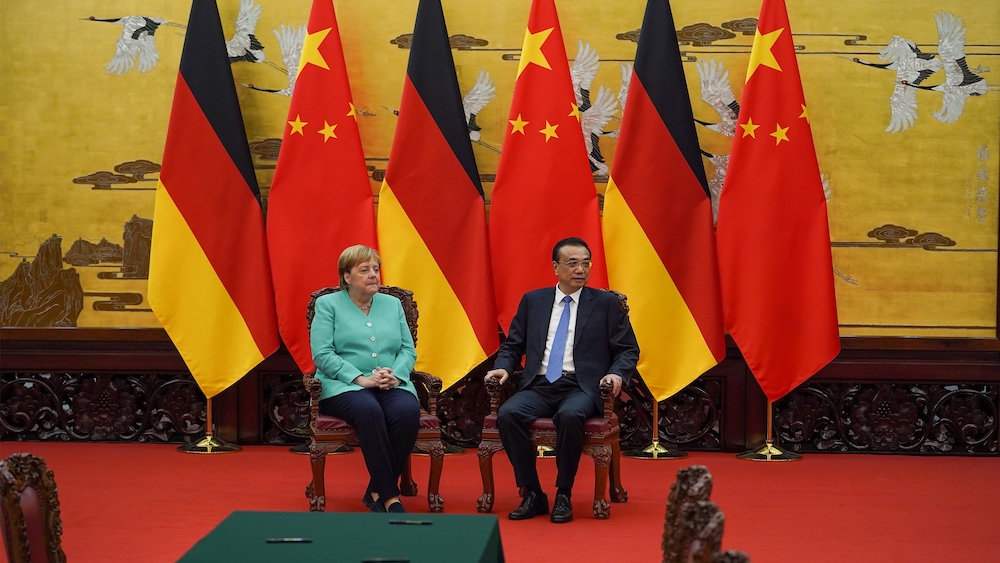

There are more than 70 bilateral dialogues between Germany and China. Among the most important are the encounters between German top managers and the Chinese leadership in the framework of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s state visits. While complaints about the conditions on the Chinese market often dominate during the run-up to the talks, in the actual conversations with the Chinese side the Germans mostly praise the good cooperation.

The fact that the managers prefer to leave the unpleasant messages to the chancellor is a something Merkel has repeatedly complained about to the business representatives.

For years, surveys conducted by German and European chambers of commerce in China have shown that foreign companies there suffer from increasingly difficult market conditions, for example due to worsening legal standards or the systemic discrimination against foreign companies. However, what is clearly apparent in surveys and is also a permanent topic in confidential discussions is not illustrated by specific examples in the press. No company wants to talk publicly about problems in China. And Chinese diplomats like to use this circumstance to refute criticism: If there really were grievances in China, why can’t this be substantiated with concrete cases? After all, one can supposedly talk about anything!

Fear of the Party State

But you cannot—at least not without consequences. Sure, there are open discussions with Chinese people. But when they occur, they are the exception rather than the rule, and proof of a particularly trusting relationship. The more the Communist Party extends its control over public discourses—in the media, in classrooms, on the Internet—the greater the worry that one might say something wrong.

Why is it so difficult for us to maintain an open dialogue with China when we can do so with the United States or other major partners? The reason is not cultural differences, which people often cite in the China case. The real reason is much more profane: We are afraid. We fear that criticism of China will have a negative effect on us: on business, on political access, on the next visa application. It’s not so much a fear of individuals, of individual business partners or interlocutors, but a fear of an increasingly autocratic political system, whose power is not restricted by laws and which employs a huge apparatus to prosecute attacks on the authority of the party.

Many incidents in recent years show that this concern is not unfounded. When a Dalai Lama quote appeared in a Daimler Instagram channel in 2018, there was immediately a wave of indignation in China. The calls for a boycott only stopped when the car manufacturer formally apologized. The Marriott hotel chain had similar problems because it had Taiwan on its list of independent countries in its booking system.

After Chinese democracy pioneer Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, Norway was inflicted with a Chinese political and economic boycott for years—despite the fact that the Nobel Prize Committee is not under the control of the Norwegian government (let alone the Norwegian salmon exporters who were excluded from the Chinese market).

Combining Political and Economic Pressure

Canada currently sees itself under similar pressure: After the Canadian police arrested Meng Wanzhou, CFO and daughter of the founder of Huawei, on the basis of an international arrest warrant, several Canadian citizens were arrested in China, including China expert and former diplomat Michael Kovrig.

This way of combining political and economic pressure has a real effect. The message is: If you are critical of China, you have to expect consequences. These often turn out to be far less dramatic than the headline-grabbing cases: permits are delayed, visas are not issued, or warnings are dropped in conversations. That’s enough to turn heads in the West. If you want smooth business or cooperation, you’d better be a little overcautious.

Often the result is heated arguments about what to say and what not to say. For example, the Federation of German Industries (BDI) published a paper in January in which it took the rather moderate position that China was not only a partner for Germany but also a “systemic competitor.” It received much praise for this unusual openness, but it also faced accusations of negligence: in China, something like this could lead to unpleasant demands and diplomatic disgruntlement that could have been avoided. This temptation to self-censor becomes fully visible when in press interviews, personalities like former German chancellor Gerhard Schroeder or Volkswagen’s CEO Herbert Diess painstakingly avoid taking a position on the detentions in Xinjiang and even claim to not know anything about them.

Distorted Discussions

From a business perspective, it’s quite understandable and, in a certain way, reasonable not to take a political position on China. Whoever is responsible for a company and its employees is therefore also responsible for ensuring that business runs smoothly. Moralizing appeals are of little use here. But on a broad scale this leads to distorted discussions, because the Communist Party has a say in what we talk about when we talk about China—not only in China, but also here in Germany and Europe.

However, with the Chinese leadership being increasingly open in its commitment to the course of authoritarian state capitalism, we have to recognize the fact that when we talk about China’s economy, we must also talk about politics. For a long time, we believed we could avoid this fact. There was hope that the economic opening would eventually be followed by a political one, and that many of our concerns would thus be resolved. This position has always been controversial, but there have always been indications that this is ultimately also the position of the Chinese leadership.

The fact that Xi Jinping began his term in office with a major reform agenda raised hopes for a new wave of liberalization. But six years later, it’s hard to avoid the reality that Chinese politics has developed differently—toward more state, more control, and more nationalism, in politics as well as in the economy.

The Limits of Misunderstandings

What can be done to hold on to China as a partner and take it seriously as a competitor? Beijing would like things to continue as before. And to interpret the West’s critical perceptions as misunderstandings. After all, China’s government insists that it is committed to the rule of law, transparency, open markets and a multilateral world order.

There is no doubt that we would prefer nothing more than for some of our criticisms to turn out to indeed be misunderstandings. For that, the impetus, however, would need to come from Beijing. The annual position paper of the European Chamber of Commerce in China, for example, sets out what steps the Chinese government could take to convince European companies and politicians that the world’s second largest economy is still on course towards open markets and a level playing field. At the end of September, the chamber published a list of more than 800 problems that concern European companies in China. The greatest wish is “competition neutrality”, i.e. equal treatment for all companies, regardless of their ownership structure.

Five Recommendations

In Beijing, Germans and Europeans can only wish. However, at home, we have a real capacity to act. So, what can we do?

First, we must openly name and admit the dilemma we are in. That may sound obvious, but it’s not. Politicians and entrepreneurs prefer to project security rather than uncertainty or fear. Academics and think tankers prefer to talk about their knowledge rather than about gaps in that knowledge or mistakes.

It’s easy to accuse others of self-censorship, but harder to admit it ourselves. Tactically weighing up what can and cannot be said in and about China is the core of our dilemma. We have to be clear about this: The things we do not talk about in China—such as the political system, the arbitrary use of the legal system or human rights—are sensitive because they are important, not the other way round. If they had no relevance, they would not be taboo.

Second, we need more media organizations, academics, think tanks and associations that are able and willing to do research without regard to political constraints and also to name critical issues. Freedom of the press, freedom of expression and research are among the central values that distinguish our political system from the Chinese one. What comes out of this is not always pleasant, undisputed or correct. That’s the nature of such things. However, a general bashing of “the China reporting in the German media” undermines the quality of our discussions, as does the sweeping labelling of positions as pro-Chinese and anti-Chinese.

Third, Germany and Europe need strategies for a world order in which our relationship with China will be difficult for the foreseeable future. As long as Beijing’s authoritarian and nationalistic course continues, we cannot avoid seeing China in many areas as a “systemic competitor” or even rival, and drawing the necessary conclusions from this.

This in no way means that the People’s Republic is our opponent or enemy. It is not! This does, however, provide the context in which we define and prioritize our own work at home. Central to this is the strengthening of Europe as an economic area and global player. That is easier said than done, but that urgency has finally been recognized in Brussels.

Criticism Is Possible

This is exactly what the incoming European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is talking about when she says she wants to lead a “geopolitical” commission. She is inheriting a number of initiatives and discussions that can be developed in the coming years: The EU’s Connectivity Strategy, first presented in 2018, aims to put cooperation with emerging economies on a new platform and provide a response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Initiatives to promote education, research and future technologies should strengthen Europe’s competitiveness. The free trade agreement with Japan shows that Europe is in a position to forge new alliances. All these are all hard nuts to crack—but they are the right ones.

Fourth, we should talk as openly as possible with Chinese interlocutors about the dilemmas in which we find ourselves. They should be made aware how unsettled we are by China’s current course and how hard we struggle to respond properly. That applies to dealing with the government as well as with individuals. For the West’s critical attitude towards China, many Chinese only have the explanation that Beijing’s party propaganda gives them: that the West wants to prevent China’s rise. If we want them to understand our view of things, we need to explain it better.

Beijing Listens

China’s government is also reliant—as strange as this may sound—on comprehension aids. Experience in recent years has shown that Beijing can listen attentively. At the recent Belt and Road summit, Xi Jinping systematically worked through the criticisms that have been levelled at the giant project for years, such as the massive indebtedness of the partner countries or a lack of consideration for sustainability. The party no longer publicly mentions its “Made in China 2025” industrial policy, at least not by name.

Whether the new rhetoric will be followed by action is still open, but the message has at least been received. Critical strategy papers from Europe, such as the Federation of German Industry’s China paper or the EU Commission’s 10-point plan, were received in China not with joy, but with respect, and did not lead to the tit-for-tat response feared by some.

Fifth, we need a positive agenda for constructive cooperation with China. Despite the current difficulties and concerns, China is an important partner for Germany – and should remain so. A decoupling strategy such as that of the US under Donald Trump is not a realistic, let alone desirable, option for Germany and Europe.

Global political tasks such as combating climate change and its consequences, implementing the UN’s sustainability goals or securing peace only have a chance of success if the largest, richest and most powerful countries work together.

Economically, Germany and China—and by extension, Europe and China—have benefited enormously from each other in recent decades. They can continue to do so. To create open and fair market conditions for this is possible and is in both sides’ interest; a realization that is political mainstream at least when it comes to words and that can be followed by action again once the wave of economic nationalist solo attempts subsides. Germany and China are also more socially networked than ever before.

The much-described era of a “low trust world” does not need to become a self-fulfilling prophecy if cooperation continues: with new openness on both sides. Europeans and the Chinese will continue to be successful together where this succeeds. And nothing creates more trust and understanding than mutual success.