Hit hard by the pandemic, there are signs that the United Kingdom may transition out of the EU later than planned. But economic carnage provides Boris Johnson with a cover for a hard Brexit.

Brexit was always an emotional rather than instrumental venture. It was based on a yearning for national sovereignty and a nostalgic view of the United Kingdom’s role in the world. Its biggest weakness, however, lies elsewhere.

Its architects could not make up their mind about which of two visions they were projecting. Was Britain going to become Singapore-on-the-Thames, a low-tax, low-regulation island of futuristic start-ups that was open to all-comers, as long as they had the skills and the thirst? Or, unshackled from the European Union, was it going to do more to protect its own, to give the state more of a say in determining and equalizing outcomes? The likes of Boris Johnson and Michael Gove—the leaders of the 2016 Leave campaign and presently prime minister and minister for the cabinet office respectively—never resolved this dilemma, because they knew they couldn’t, and because they wanted to have their cake and eat it.

June Is the Real Deadline

Now, with COVID-19 tearing apart lives and communities, exposing the lack of planning, strategy, and investment in the National Health Service and decimating the economy, logic might dictate that the government let up in its determination to meet the December 31 deadline for the transition period out of the EU. Not a bit of it, say ministers, displaying the same hubris that led them initially to dismiss the coronavirus as a serious threat to the UK.

According to one adviser, those around the prime minister believe they can still make the deadline—even though that deadline is not actually the end of the year, but the end of June. As the Withdrawal Treaty states, any request for a one- or two-year extension must be submitted by then.

With the two men at the heart of the negotiations, the EU’s Michel Barnier and the UK’s David Frost, having previously been struck down by the virus, and with discussions only now resuming by video link after a sizeable pause, the chances of any meaningful agreement in weeks are negligible at best.

The aim is a free-trade agreement, with a zero-quota, zero-tariff deal similar to the one the EU agreed with Canada (after years of talks). They also have to tackle aviation, nuclear energy, international security, and the small but politically vexed question of fisheries. Thus, the timetable was always going to be ambitious. When the first round of negotiations began, the two sides admitted that they faced “very serious divergences.”

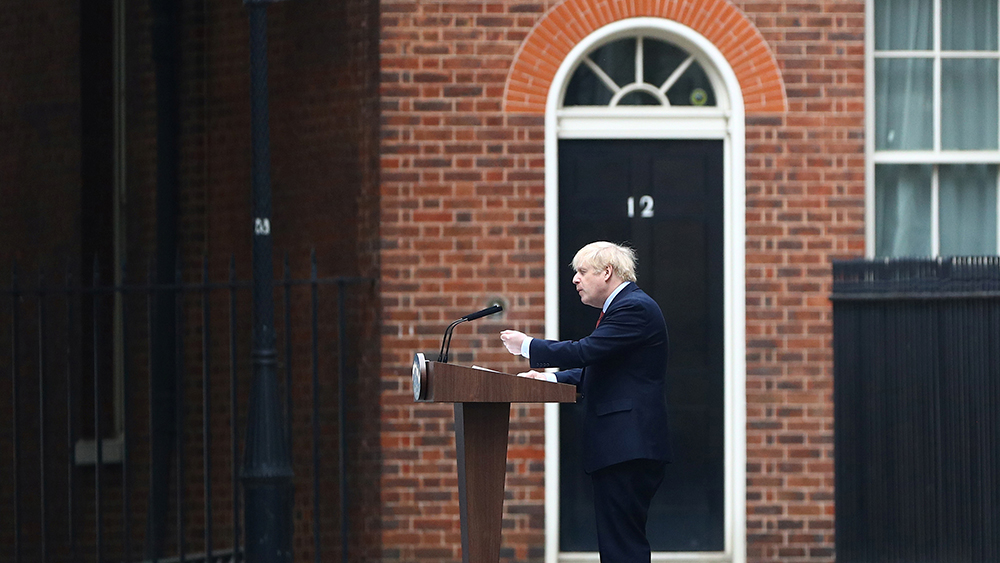

Johnson’s Corona Setback

Bizarrely, given how much of a mess his government has made of its response to the pandemic, Johnson is politically unassailable. His 80-seat majority in the House of Commons gives him legislative carte blanche. His opinion poll ratings are sky high, boosted by a sympathy vote after he was admitted to hospital with the coronavirus. The Labour Party’s new leader, Keir Starmer, will provide a much more forensic opposition than Jeremy Corbyn ever did, but he will take some time to make a mark in this “wartime” setting.

Longer term, Johnson knows that COVID-19 has delivered a setback to his plans to remake Britain in his image. He knows that he cannot opt for a low-tax regime, such will be the UK’s indebtedness. He also knows that he will not be able to lavish money on his pet projects. Thus, there will be no Singapore-on-the-Thames nor will there be a great social transformation.

Yet, as one former aide to Theresa May points out, Johnson has nowhere else to go. “He has to make this new political geography work. He has to make this realignment permanent. They will be desperate for the budget not to be swept away.” The advisor was referring to the so-called Red Wall, the constituencies in the North of England and the Midlands that had been traditionally Labour, but were won over to the Conservatives in last December’s general election because of their twin pledge to “get Brexit done” and to invest more in their regions.

On his victory, Johnson thanked those voters for “lending” their support, knowing that they could easily transfer it back if they felt the promises had been broken. Hence his visceral reluctance to “do a May” on Brexit, to follow his predecessor in delaying the departure process, irrespective of the circumstances. In addition, if he is unable to make as much of a difference in domestic policy as he had hoped, then Brexit becomes even more talismanic for him.

Oven-Ready or Not

When Johnson declared during the election campaign that a deal “was oven-ready,” it seems he meant it. Or rather he meant that he believed the country was ready for either leaving without a deal or with the most minimalist of deals, both of which translated into the hardest of Brexit and future trading on World Trade Organization terms—plus a special protocol for Northern Ireland. He didn’t even see the point of an accord on security matters or on aviation.

The plan was, literally, to get it all done as soon as possible, both the January 31, 2020, departure and the December 31, 2020, end of transition. The idea was to absorb the economic shock early in the cycle of the parliament.

The British economy might have been just about robust enough in normal times, but now? The counterargument is that, given that a post-COVID-19 recession (or depression) will last years and not months, a short-term delay will not make much difference. That is a cavalier approach—but Johnson is a cavalier politician.

Downing Street has other rhetorical weaponry to deploy. First of all, it can argue that the UK will be saving money by not paying any more into Brussels’ coffers. That is correct, in a narrow sense. It can also point to the fact that the EU has hardly covered itself in glory during the pandemic, closing borders, slapping bans on the export of vital equipment even within Europe, fighting over coronabonds, and the richer North refusing to help out the poorer South, as happened during the eurozone debt crisis a decade ago.

At the same time, the UK cannot point to a single area where being outside of the EU’s institutional framework has helped it plan logistics and purchase equipment to tackle the virus.

U-Turn in the Offing?

Johnson, like Margaret Thatcher, manages the twin feat of sounding unyielding while being perfectly willing to compromise or make a U-turn. The easiest way for him to agree to a delay is if both sides agree to it jointly. This would require Barnier’s agreement as the current requirement is a request coming from London. Any joint agreement could be dressed up as technical and purely in light of the COVID-19 crisis.

Already ultra-Brexiteers are crying foul. They started to sense something was afoot when a former Tory MP, Nick de Bois, who had served as chief of staff to Dominic Raab, now the Foreign Secretary, penned an opinion piece in the Sunday Times newspaper in early April explicitly calling for a delay. “First, it would be incomprehensible to many members of the public if this government devoted time and energy on these talks until the pandemic was under control. The controversy over testing policy and logistics illustrates how intense government efforts must both be and seen to be,” he wrote. “Second, it will strike business, already on life support, as utterly illogical and inconsistent with the government’s efforts to support business, to impose the prospect of greater disruption by not extending the transition period.”

Nigel Farage, who since the December 2019 election has fallen off the political radar, sensed an opportunity when the question of a delay was first mooted. “We need to be free completely of the EU so that, as we emerge from the crisis, we are free to make all of our commercial and trade decisions,” he told his dwindling band of supporters. Tory MPs and former ministers are making similar noises.

The more “Remainers” or “soft Brexiteers” advocate a delay, the harder it will be for Johnson politically. In any case, the final decision will be guided by public opinion. Polls currently show a small majority supporting a delay, although that number drops sharply among ardent “Leavers”. Most floating voters were relieved to have forgotten about Brexit and have little desire or cause to think about it during the pandemic.

Stretching the Truth

Downing Street has already been stung by well-sourced media accounts of how Johnson paid little attention to the coronavirus outbreak during the crucial five weeks from the end of January (while the Germans and others were frantically trying to prepare themselves). He was too busy celebrating “Brexit day” and planning his assault on institutions from the BBC to the civil service. He knows the public will not tolerate another “distraction”.

In the end, if there is no trade deal, and if the UK leaves at the end of the year in the midst of post-corona economic carnage, Johnson will have made his decision on a precise calculation. One of his considerations will be this: voters, no matter how much they suffer, would not be able to disaggregate his move. He could say that Brexit had nothing to do with it. He could lay the blame entirely on the pandemic. It wouldn’t be the first time in his career he had—to put it ever so politely—stretched the truth.