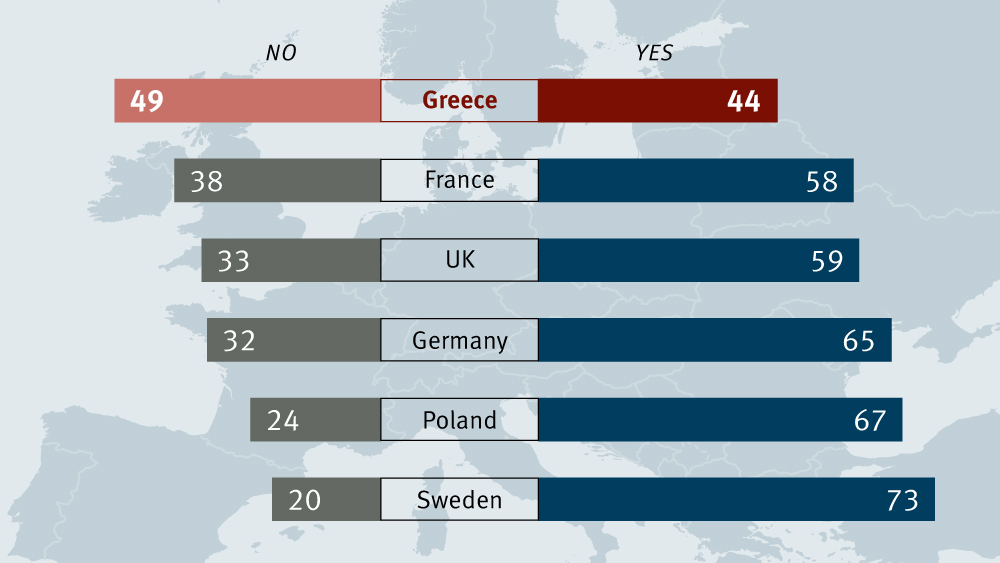

“Should the EU support Ukraine even if this damages relations with Russia?”

Shortly after winning the Greek elections in January, the new Syriza government sprung a surprise on its European partners by dramatically changing its tone on Russia.The cabinet would “take its time” to decide whether to support continuation of sanctions against Moscow, Defense Minister Panos Kammenos, leader of Syriza’s right-wing coalition partner Independent Greeks (ANEL), told the German weekly DIE ZEIT. This represented the first crack in an otherwise unified front. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras set alarm bells ringing in Brussels again when he visited Moscow in early April 2015, hinting that he might ask Russian President Vladimir Putin for financial support. On a visit the previous April, two months after Moscow’s annexation of Crimea, he had echoed the Kremlin line that “fascists and neo-Nazis” were running the show in Kiev.However, Greece’s newly empowered populists are not unique in their special relationship with Moscow (though it should be noted that Syriza has roots in the pro-Russia Greek Communist Party). There are strong cultural and historical ties between the two countries; after all, Russia and Greece share the Orthodox Church. But there is still more to it.

First, Greeks have indeed been more reluctant than other Europeans to become involved in the Ukraine crisis. When the German Marshall Fund’s Transatlantic Trends survey asked in June 2014 – before the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 – if the European Union should continue to provide economic and political support to Ukraine despite the possibility that this could exacerbate relations with Russia, 44 percent of Greeks – less than in any other country in Europe – agreed, while 49 percent of Greeks said that it should not. Greeks generally supported measures to strengthen Ukraine, such as offering NATO and/or EU membership, but were considerably warier of steps challenging Moscow directly, opposing both the provision of military supplies and equipment to Ukraine as well as stronger sanctions against Russia.

To be sure, there is an element of euroskepticism in the Greek attitude toward Ukraine: among those Greeks who feel ill-served by the EU – and there are many, with 42 percent of the country saying that membership has overall been bad for Greece – there is reluctance to toe the EU line. Among the 85 percent of Greeks who agreed that the EU had not done enough for the countries affected by the economic crisis, most opposed strengthening sanctions against Russia. Among the 12 percent who said that the EU had in fact done enough for the crisis countries, a plurality supported stronger sanctions against Russia.

But Greece going wobbly on anti-Kremlin sanctions is not just about frustration with the EU. Pew’s 2012 Global Attitudes survey found more sympathy for Russia in Greece than in most other EU countries. That year 61 percent of Greeks expressed a favorable opinion of Russia, as did 63 percent in 2013, and 61 percent again in 2014; in Germany, on the other hand, 64 percent of respondents expressed an unfavorable view of Russia in 2012, as did 64 percent in France, 67 percent in Italy, 60 percent in Poland, and 54 percent in Spain. Greeks just like Russia more than most other Europeans do.

Moreover, Greek affinity for Russia may have more to do with nostalgic memories of the Soviet Union’s support for the Greek left’s opposition to the Regime of the Colonels in the 1970s than a feeling of solidarity with Moscow today. When the 2014 Transatlantic Trends results are broken down by age, it turns out that younger Greeks are often less fond of Russia than their parents or grandparents. Of Greeks aged 18 to 24, 57 percent said their opinion of Russia was favorable – compared to 74 percent of Greeks over 65.

And breaking down the results along partisan lines shows that the right wing in Greece is actually friendlier toward Russia than the left, possibly in part thanks to Putin’s identification as a defender of “traditional” values. Of self-identified left-wing Greeks, 51 percent said Russian leadership was undesirable, while 66 percent on the right said it was desirable. On the right, 53 percent said that the EU should not continue to support Ukraine, compared to only 47 percent on the left.

Syriza may frighten Brussels, but there is more behind Greece’s affinity for Russia than can be explained by party alliances alone – as these numbers show, keeping Athens in line on Russia policy may be trickier than expected.

Read more articles from the April 2015 issue FOR FREE in the Berlin Policy Journal App.