With Germany’s political landscape in upheaval, observers of German politics may be excused for thinking that the world is caving in.

In late May, the troubled Social Democrats (SPD), one of the main political parties both in Germany and in Europe’s wider center-left, suffered a disastrous double blow that underscored the party’s existential crisis. The Social Democrats won only 15.8 percent of the vote in the European Parliament elections, down from 27.3 percent in 2014, finishing behind the Greens for the first time ever in a national election. On the same day, the SPD failed to top the poll in Bremen, coming second to Angela Merkel’s center-right Christian Democrats (CDU) in the northern state it has governed for more than seven decades. Shortly afterwards, party leader Andrea Nahles announced her resignation after just a year in office.

The SPD’s collapse has been accompanied by the rising fortunes of the German Greens, who won nearly 21 percent of the vote in the European elections—double their previous result. Crucially, the Greens won the youth vote. Among those under 25, the Greens attracted more voters than the combined tally for the SPD and the CDU, together with their Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union (CSU). The success of the Greens and the losses of the governing parties were well predicted in the polls, but the results are still bewildering. Opinion polls conducted since have even seen the Greens pushing ahead of the CDU/CSU to 27 percent, making them the main center-left force and the most popular political party in Germany for the first time in history.

The “Greta Effect”

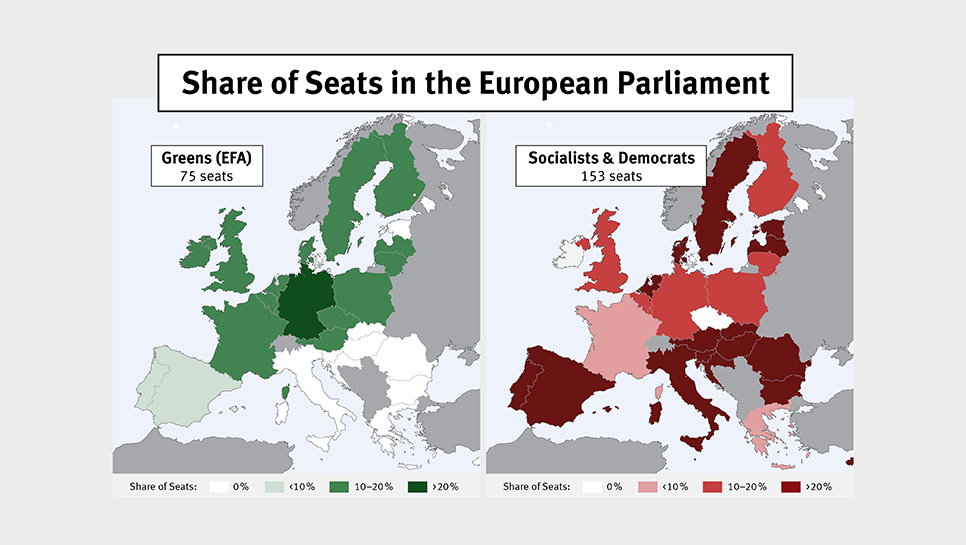

The crisis of the Social Democrats and the rise of the Greens are not unique to Germany, though both effects are particularly strong there. The overall European picture after the elections is marked by a curious divide: In several countries in the north and the center of Europe, the Greens have successfully taken votes away from Social Democratic parties; whereas in the southeast, the Social Democrats seem to be recovering, and the Greens have not done particularly well.

In a similar trend as in Germany, the British Labour Party, the Romanian PSD, and the Austrian SPÖ all suffered disappointing results. The French Socialists (PS), which secured 14 percent of the vote in the 2014 election, were nearly obliterated. In contrast, the French green party EELV surged to a surprising third place, scoring from 8.9 percent to 13.5 percent of the vote. The Greens also reached double figures in several other countries, coming in second in Finland and third in Luxembourg. In the United Kingdom, the Green Party finished ahead of the ruling Conservatives with a score of 11.8 percent. Ireland’s Green Party’s vote trebled in comparison with the 2014 elections, putting it in line to send representatives to the European Parliament for the first time in 20 years. Greens in Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands also did well in the wake of recent electoral successes in regional polls, as many young voters increasingly turn away from the center-left to vote for the environmentalist parties.

Only a couple of years back, opinion polls suggested that the Greens were going to see their support halved in the European Parliament. Instead, their total of seats has now gone from 52 to 75, pushing them into a position of influence. Analysts explain this “Green wave” with the “Greta effect,” referring to the teenage Swedish climate activist, Greta Thunberg. What is certain is that Green parties have benefited from the fact that it was climate change, rather than migration, that dominated the political agenda and the election campaign in many countries.

Europe’s Southeast is Different

Yet not all member states have been hit by the green wave. In fact, it was largely confined to countries in north-western Europe. The Greens’ gains there masked losses in Austria, Spain, and Sweden in the European elections, and the total wipeout of Green MEPs in Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia, leaving the Green group unrepresented in 12 out of 28 member states. Indeed, most Green parties across the EU failed to make significant gains compared with 2014.

With a few exceptions, Green parties have not been able to consolidate their presence in the south and east of the EU, “a political reality that even the latest wave of stunning European electoral success has not changed,” according to an analysis by the economic news service Eurointelligence. The Greens won no seats in Eastern Europe and only a handful in southern Europe, where a number of Social Democratic forces have co-opted environmental concerns into their platforms, and thus resisted the green trend, including the main center-left parties in Portugal, Spain, Malta, and Italy.

In Spain, a decisive win for the center-left PSOE, taking 33 percent of the vote, seems to provide evidence of a recovery. This result has made the PSOE the largest national delegation in the S&D group, with 20 MEPs, ahead of the Italian Democratic Party (PD), which is also starting to climb back up according to the latest polls. In Portugal and Malta, the governing parties of Prime Ministers António Costa and Joseph Muscat won by a landslide with 33.4 percent and 54.3 percent of the vote respectively. Polls predict an even bigger win for Portugal’s Costa when he stands for re-election in the fall. The Danish center-left Social Democrats also won the European elections and the subsequent general election held on June 5, though the party’s focus on a more restrictive immigration policy is probably not a model for Europe’s other Social Democrats in crisis. Nonetheless, their win is the third in less than a year for center-left parties in Nordic countries after successes in Sweden and Finland.

Environmentalism may primarily be a concern in north-western Europe, and the Social Democrats may yet experience a comeback in other countries and regions of the the EU. Nevertheless, it is likely that this moment will be remembered as a turning point for the Greens: for the first time, they have taken a place among the big players in the European Parliament.