Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani is everyone’s darling at the moment, but the international community would do better to approach Tehran with greater caution.

When it comes to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, the international community would do well to keep its feet firmly on the ground. There is no guarantee that the recent nuclear deal will give him more power in Iran. Yes, Rouhani is popular at home. Why wouldn’t he be? With Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s blessing, Rouhani’s Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif, managed to reach an agreement with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany, the P5+1, to suspend all nuclear sanctions against Iran. Zarif’s diplomatic skills made a tremendous contribution to the success of the talks, and the people of Iran know it. Gone are the days when nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili would put Western negotiators to sleep with his whiny voice and diatribes against the United States.Theoretically speaking, such an achievement should give Rouhani more leverage in Iranian politics. But realistically, that’s unlikely.

In fact, Rouhani could end up politically weaker. For one thing, in post-revolution Iran the government operates one level below the revolutionary institutions created after the 1979 overthrow of the shah, making it weaker in terms of power and institutional influence. The constitution was designed to keep the government weaker than the post-revolution institutions to ensure that it could never challenge the supreme leader and the revolution itself; many current government institutions existed under the shah, and there was concern that any structure that remained from his regime could one day challenge the revolution. There were similar concerns regarding Iran’s armed forces, called the Artesh, which had served the shah. These concerns were later proven to be well founded: on at least one occasion in July 1980 members of the armed forces were revealed to be planning to overthrow the new regime.

Just as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) was created after the revolution to make sure the Artesh could never pose a serious threat, other “revolutionary” institutions, most notably the Guardian Council, were created after 1979 to ensure that the government could never challenge the revolution or the supreme leader. This is why the Guardian Council is more powerful than the government, and why one of its jobs is to keep the government in check, albeit indirectly, by qualifying or rejecting candidates who can run for parliamentary elections. By qualifying the majority of the opposition factions to run for parliamentary elections (thus guaranteeing their success), the Guardian Council limits the government’s power.

Meanwhile, the IRGC can also make life difficult for the government, even though – constitutionally speaking – it is not supposed to become involved in politics. Today, the IRGC is a major player in Iran’s economy, with a presence in many important sectors, including energy, construction, telecommunications, automotive, banking, and finance, where it plays a dominant role. This makes it very difficult for the government to open up the economy to competition or investment, and, as events at Tehran’s Imam Khomeini airport in May 2004 demonstrated, when armed IRGC men simply took the airport by force from the Austrian-Turkish consortium supposed to run it, the Guardian Council is not shy about using its military arm to push out foreign investment firms it does not approve of. …

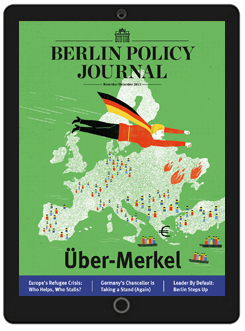

Read the complete article in the Berlin Policy Journal App – November/December 2015 issue.