Germany is hosting an estimated 600,000 refugees from the civil war in Syria. The Goethe Institute, Germany’s international cultural association, was forced to close its hub in Damascus four years ago. But, in an exceptional role switch, it has now brought a taste of Syria’s vibrant culture to Berlin.

Amer El Akel, a young Syrian artist, reads aloud from the endless official mail he has received since arriving in Germany as a refugee. They are letters concerning his legal status in the country but also from service providers like Deutsche Telekom, containing pages and pages of tiny print. In stilted German, he stumbles over virtually every other word.

His performance piece is both an amusing comment on German bureaucracy and a serious exploration of the sense of alienation experienced by refugees. It featured in a series of events called “Damascus in Exile” staged by the Goethe Institute in a tiny empty shop on Rosa-Luxemburg-Strasse in central Berlin.

The shop is a far cry from the original Goethe Institute in Damascus. Located in the unprepossessing but sizeable former embassy of the German Democratic Republic, it was an important cultural center until it was forced to close in 2012. Though not immune from the censorship of Bashar al-Assad’s draconian regime (programs had to be approved by the Culture Ministry), it was a place of learning with an impressive library and a lively program that attracted many Syrian artists.

In 2012, the German Foreign Office advised German nationals to leave Damascus as the civil war escalated. Goethe Institute staff were let go on full pay for a year in anticipation they would be able to return within months. “We thought we would be back soon,” says Johannes Ebert, Secretary General of the Goethe Institute.

Since then, four years have passed, and there is still no prospect of the war ending. What began as a movement for freedom and democracy has developed into a proxy war with global powers supporting opposing sides. While Germany has taken in an estimated 600,000 Syrian refugees, its role in the region is limited to humanitarian assistance. Though Chancellor Angela Merkel has said that addressing the causes of flight is a central pillar of her refugee policy, Germany is watching the war helplessly from the sidelines.

Among those who have found refuge in Germany are many Syrian artists, writers, musicians, performers, theatre directors, and film-makers.

“Just like Being at Home”

The idea of setting up a “pop-up” site was in a sense outside the mandate of the Goethe Institute, which only receives government funding for its work abroad.

“We thought we could make an exception,” says Pelican Mourad, who was program assistant at the institute in Damascus. Part of her concern was that extremist organizations are trying to recruit newcomers. “We needed to counter that by creating a space for free-thinkers and artists,” she says.

Artists who took part ranged from young talents like Akel to established names such as the clarinetist and composer Kinan Azmeh, who is scheduled to perform at Hamburg’s vast new Elbphilharmonie with Yo-Yo Ma in January. “We worried he would object to the tiny space” in the Berlin shop, where enthusiasts spilled out onto the street during his concert, Mourad says. “But he said it was just like being at home in Syria.”

Many of the works dealt with the civil war. Liwaa Yazji’s harrowing film “Haunted” describes the horrific living conditions faced by those forced to flee their bomb-devastated homes and desperately seeking shelter in war-ruined towns. Others addressed the lot of the refugee: Daniel Carsenty’s film “After Spring Comes Fall” tells the story of a young Kurdish woman who flees Syria and arrives in Berlin illegally, where she is tracked down by the Syrian secret service.

At a podium discussion, participants discussed what culture can achieve for refugees. Theatre director Mohammed Al-Attar described the difficulties of trying to work with people who are cold or hungry. “They have to eat, they have to have shelter,” he says. “Then comes cultural work.”

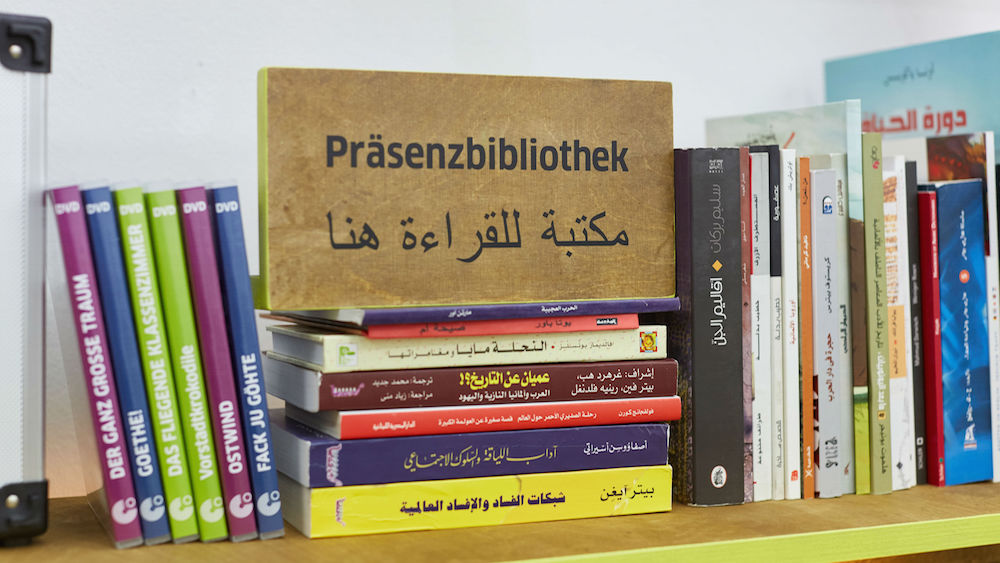

That is where the Goethe Institute comes in. It brings culture to refugee areas in Lebanon and Jordan with “idea boxes” that can be transported in a container and tour the region with books and films translated into Arabic. Programs have included acrobatics and stilt-walking as well as soccer for traumatized children in Lebanon.

Increasingly, the institute is putting expertise gleaned in the Middle East to good use at home. It has received some large donations, including one from the Japan Art Association, allowing it to operate in Germany even without government funding, Ebert says. Materials that may seem of secondary value in the field, such as an app that teaches basic German in eight weeks, can prove crucial in Germany – as Akel’s struggles with the language of bureaucracy show.

“Part of the refugee experience is boredom,” Ebert says. “Once basic requirements are met, the need for culture and education follows very closely.