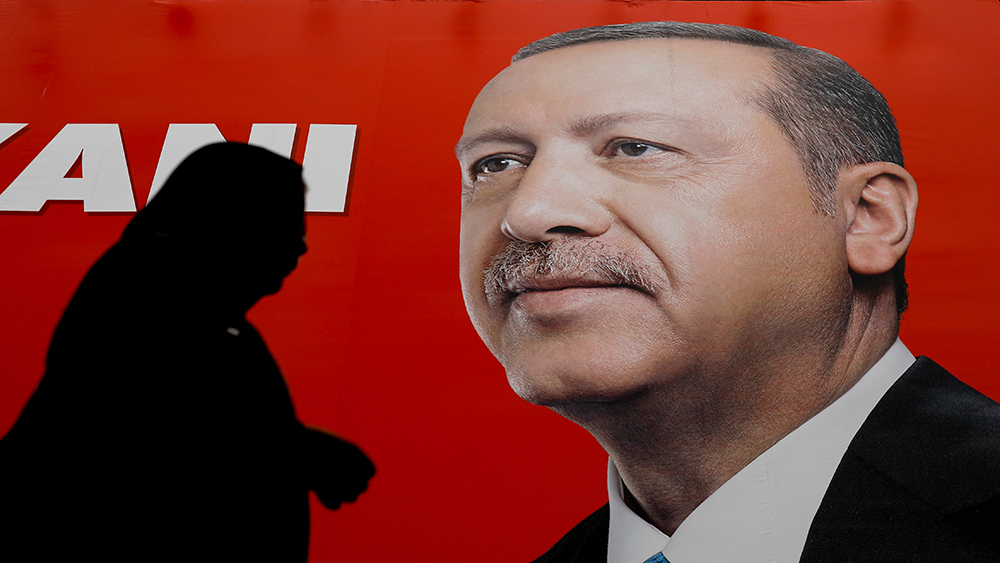

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is visiting Germany, hoping to improve relations with Berlin. However, progress hinges on Turkey’s government reversing its slide into authoritarianism.

The state visit to Germany by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan which starts on Thursday shapes up as one of the most controversial in recent memory. It has already met with intense resentment from Germans, critical of Erdoğan’s seemingly irreversible slide toward authoritarianism and repression of the opposition.

Anti-Erdoğan demonstrations have already taken place in nine major German cities, including Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt, and Stuttgart over the weekend. The German Federation of Journalists and Amnesty International are organizing a protest at the Berlin’s main railway station for September 28, while a protest led by Alevi groups (the largest religious minority in Turkey) and one of Germany’s largest trade unions, Ver.di, is scheduled to take place the next day in Cologne. Meanwhile, a number of leading politicians have expressed their displeasure that Erdoğan will enjoy an official state dinner with German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier. While Chancellor Angela Merkel has signaled she will not attend (she rarely takes part in state banquets of visiting heads of states), Cem Özdemir, a prominent former leader of the Greens (and of Turkish descent) who is fierce critic of the Turkish president will be among the dinner guests: “Erdoğan has to suffer me,” he said.

The fact that the visit is still going ahead, despite such push-back, is significant. It is indicative of Ankara’s strategic importance to Berlin. Indeed, the meeting between Erdoğan and Merkel will be the third high-level meeting between German and Turkish officials within less than a month. Germany’s Foreign Minister Heiko Maas had traveled to Turkey on September 5-6, and Berat Albayrak, Turkey’s minister for economy, was in Berlin last Friday for talks with Olaf Scholz and Peter Altmaier, Germany’s ministers for finance and economy, respectively.

This week’s controversial visit, too, will be focused on repairing relations and keeping them steady. Syria and the situation in Idlib apart, at the top of the agenda will be Turkey’s economic troubles. To Erdoğan’s dislike—and very likely in line with what Merkel will put forward—any feasible way out of Turkey’s predicament will require Ankara to build up its democratic credentials.

Strategic Importance

Erdoğan’s visit comes on the heels of an escalation of tensions between the United States and Turkey last month, when US President Donald Trump slapped sanctions on two Turkish ministers and doubled tariffs on imports of Turkish steel and aluminum.

The showdown unnerved international markets, pushing Turkey’s already ailing economy over the edge. The Turkish lira plunged to a series of record lows, losing over 40 percent of its value to the dollar at the height of the crisis. After years of over-borrowing in foreign currencies, Turkish corporates and banks are now on the hook for over $300 billion, nearly half of which will mature within a year. With a depreciating currency, it is much more difficult to service these loans in foreign currencies that were accumulated when the lira was much stronger. And if these loans cannot be financed, there is a chance that Turkey’s economy could collapse.

For Germany, this is an alarming prospect—and is connected to why Berlin is now interacting with Ankara across multiple levels of government.

With a population exceeding 80 million, Turkey carries a massive market potential for German and European exports. It was Germany’s sixth largest trading partner outside of the European Union last year and the EU’s fifth largest—ahead of such countries with substantial economies as South Korea and India.

Furthermore, the EU has consistently ranked as the top destination for Turkish exports. Last year, 47.1 percent of Turkey’s exports went to the EU. In fact, the EU has attracted over 40 percent of Turkish exports every year over the course of the last decade, with the exception of 2012, when the EU’s share was still 39 percent. Germany has led the list of Turkey’s largest export markets for over a decade, drawing 9.6 percent of Turkish exports in 2017. Also, the EU invests heavily in Turkey,and no EU country is more active than Germany, with 7,000 companies currently in operation, including such big names as Bosch, Siemens, and Mercedes.

Curbing Migration Flows

But there is another—an arguably more important—reason why Germany is interested in fixing Turkey’s ailing economy: it is linked to Turkey’s curbing immigration flows into Europe.

This issue has become more acute with the impending assault by the forces of the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, supported by Russian air power and Iranian-backed militias, on Idlib—a Syrian province 50 kilometers south of the Turkish border and the last rebel stronghold standing in the country. Idlib’s population is estimated to have soared over three million after seven years of fighting, and an assault would displace hundreds of thousands of civilians, including many jihadists, along the Turkish border.

Turkey is already struggling to host the 3.5 million Syrian refugees it has admitted since 2011.The presence of these refugees has since become an irritation, and is seen by the Turkish public as a disruption to public order and safety. With the economy faltering and unemployment rising, the migrants are now seen as burdens on the state’s resources. In the event of an exodus out of Idlib, Turkey could not afford to, and would in fact not want welcome another refugee influx.

In return, Germany fears that Turkey may not be able to uphold the migration agreement it signed with the EU in March 2016: in exchange for €3 billion (and the same amount at a later date), Turkey committed to preventing irregular migrants from crossing into Europe and taking back and hosting those Syrians who did make it to Greek shores. If the deal falls through, it could unleash another wave of refugees toward Europe’s borders.

As the violent demonstrations against foreigners in Chemnitz in early September showed, the decision to admit one million refugees in 2015 still dominates and gridlocks German politics. In this sense, Germany needs a strong-performing Turkish economy – so that it could keep serving the purpose of a buffer state.

Revisiting the Customs Union

However, Germany’s options for directly extending financial assistance are limited.

Dispersing a lumpsum is out of question, since 72 percent of the German public would not support such a move, as revealed by a recent Deutschlandtrends survey, understandably fed up with Erdoğan’s comparison of the German government to the Nazis and the rampant human rights violations in Turkey. Instead, Germany needs to work through a rules-based, institutional framework that will not be framed as a “gift” to Turkey.

Re-exploring the modernization of the customs union looks more promising, however. Turkey and the EU have been in a customs union since 1996 that removes tariffs on manufactured goods and processed agricultural products. Upgrading it would expand the arrangement into services, agriculture, and public procurement, diversify the range as well as increase the volume of Turkey’s exports to the EU, and thereby contribute significantly to its economic well-being.

Although the European Council suspended any further debates on the topic indefinitely, Albayrak brought it forward last week in his meeting with Scholz and Altmaier. It is also likely to come up this week in the Erdoğan-Merkel meeting.

Fixing Turkey’s Democratic Edifice

To open and move the negotiations forward, however, Turkey’s democratic practice (both within and outside the country) will have to undergo a substantial uplift. Indeed, the customs union with the EU is more than just a trade agreement; it also presupposes a well-functioning justice system, operating with the principle that strong economic links could only co-exist with rules-based governments on both sides. Re-examining it would therefore require Turkey to harmonize its rules, regulations, and institutions, both economic and political, with those of the EU.

This means that Turkey must make significant improvements to the rule of law and independence of the judiciary, as well as release the human rights activists and journalists currently serving unlawful prison sentences, including an unfortunate number of German citizens. After the recent reshuffling of the editorial board at the daily Cumhuriyet, which basically snuffed out Turkey’s last-standing voice of opposition, much will also have to be done to re-forge a climate that fosters freedom of expression and the media.

Merkel will also want to see an end to Turkey’s meddling in Germany’s domestic affairs.

Erdoğan has previously used his visits to Germany to speak to huge crowds of German-Turks, an overwhelming percentage of whom have supported Erdoğan in recent elections. He treated his last two appearances—in Cologne in 2014 and Karlsruhe in 2015—as an extension of his election campaigns, invoking incendiary language to exploit the vulnerabilities of the German-Turks, who have long claimed that they have not been able to integrate well into German society.

Merkel’s government has in return expressed its frustration with these rallies, charging that they fuel inter-communal tension. The fact that no such speech is planned for the upcoming visit should come as a relief.

However, the Turkish Embassy in Berlin has said that Erdoğan may deliver brief remarks at the opening of a new mosque in Cologne on September 29. This could evolve into a thorny issue, mainly because Erdoğan mentioned in a recent speech that Turkey’s Diyanet, the Directorate of Religious Affairs, had funded the building of the mosque. This contradicts the statement by the Turkish-Islamic Union of Religious Affairs (DITIB), which oversees the almost 900 mosques in Germany, that the project was realized through contributions from the community of believers.

No Free Way Out

Granted, should the meeting be absent of any substantial commitment from Erdoğan to changing his authoritarian style and the Syrian regime proceeds with an attack on Idlib, Merkel will have to find another way to contain the fallout. This could involve channeling funds specifically for the upkeep of refugees, but will not result in any substantial and fundamental improvements to Turkey’s economy.

Any such progress will only be possible if Turkey stops its democratic backsliding. As Merkel stated, helping Turkey is in Germany’s interest—but it cannot do so while its citizens remain imprisoned in Turkish prisons on spurious charges and Ankara’s actions violate EU’s values and principles. Once can only hope that the Turkish leadership finally accepts this fact and acts accordingly—for the simple reason that there is no other way forward.