For those who think the British vote to leave the European Union was a mistake, there are plenty of villains to blame: from the Tory leaders jockeying to better their political positions and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s half-hearted push to remain to UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage’s constant stream of vitriol. But there is one narrative emerging that distributes responsibility much more broadly: that the Brexit referendum was one pitting generations against one another, with older Britons wanting the United Kingdom out of the EU and younger Britons voting to stay.

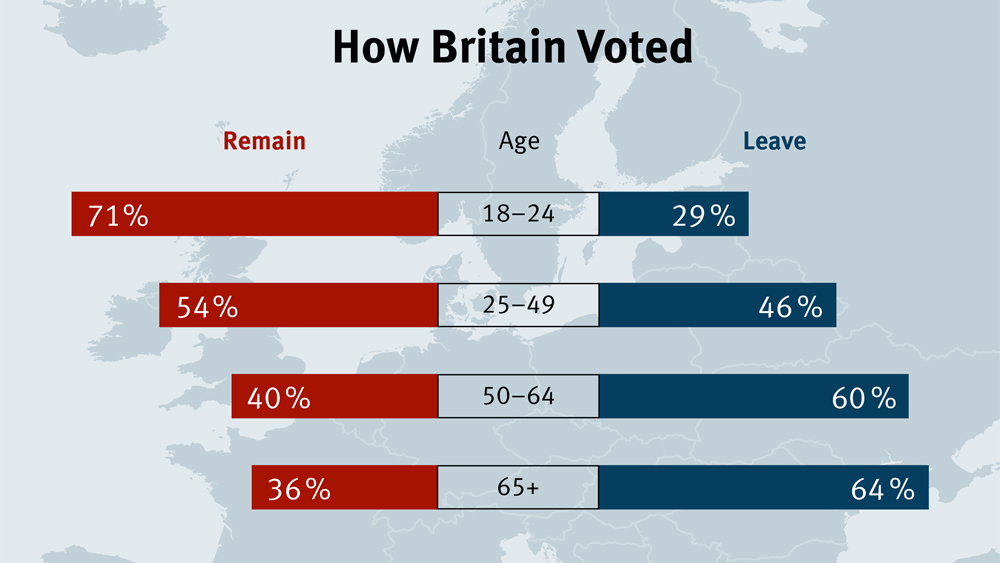

According to polling by YouGov, the best predictors of voting behavior were age and education level. And while the overall result was close, the gaps between the young and the old, the more and less educated, were dramatic. Seven in 10 voters between 18 and 24 voted to stay in the European Union, compared to 54 percent among voters 25-49 years old, 40 percent among voters aged 50-64, and only 36 percent among voters older than 65. Among voters with a secondary school education at most, seven in 10 voted to leave the EU; among those with a university degree, seven in 10 voted to stay.

In fact, this is not a pattern unique to the UK. According to the Pew Research Center’s spring 2016 Global Attitudes Survey, younger Europeans are more likely to have a favorable opinion of the EU in nearly every member state. Adults between 18 and 34 have an opinion of the EU that is 25 percentage points more favorable than adults over 50 in France (56 percent vs. 31 percent), with differences of 16 percentage points in the Netherlands (62 percent vs. 46 percent), 14 percentage points in Poland (79 percent vs. 65 percent), and 14 percentage points in Germany (60 percent vs. 46 percent).

Mind the Age Gap

The autumn 2015 Eurobarometer survey reflected a similar gap: Half of the Europeans surveyed between 15 and 24 had a favorable opinion of the EU, compared to 39 percent between 25 and 39, 37 percent between 40 and 54, and only 33 percent 55 or older. Nearly half of respondents between 15-24 trusted the EU, compared to only a quarter of those over 55. This discrepancy extends to Britain, where significantly more respondents between 15 and 24 said they trusted the EU compared to older Britons.

Part of this has to do with what kind of associations Europeans make with the EU: More than half of Europeans aged 15-24 said the EU means freedom to travel, work, and study anywhere within the EU. Among Europeans over 55, that numbers drops to 42 percent. Meanwhile, significantly more Europeans over 55 say it means a “waste of money,” “bureaucracy,” or “not enough control at external borders.”

Opposition to the EU is about more than regulations and taxes: it is increasingly about older generations, feeling left behind by the forces of globalization, who are cut off from the benefits of a digital, mobile economy while exposed to its negative effects.

Holger Geissler, head of research at YouGovʼs German office, sees this pattern just as much in Germany. “The younger the people, the more open they are to internationalism. They are much more open to immigrants, and much more open to Europe.”

No “Gerxit” on the Cards

A fifth of Germans between 18-24 say that the country could take many more refugees, compared to 12 percent among Germans 55 and older. Meanwhile, 36 percent of Germans 55 and older say the number is already much too high, compared to 16 percent among Germans aged 18-24. Thirty-two percent of Germans 55 and older say they would support Germany leaving the EU, compared to only 15 percent of Germans 18-24. The differences are even starker when one compares regions in Germany, with those in the former East feeling “left behind” by the global marketplace – and resentful of how they believe it has changed their country.

Would Germany ever actually leave the union? Is there any reason to fear a Gerxit? Geissler says no: “Germany is much more positive on the EU.” Nevertheless, the forces that led the UK to leave do not stop at the English Channel. For many older Europeans, the EU represents a new and frightening world, one they would just as soon not be bothered with.

Read more in the Berlin Policy Journal App – July/August 2016 issue.