The key to energy transition is energy replacement—quitting coal. That’s proving difficult for Poland, for whom EU climate policy is trending in the wrong direction.

The public discourse about the energy transition tends to focus on the additive side: can we add enough wind turbines so that they produce a quarter of our electricity? From a climate protection point of view, however, it is the subtractive side of the transition that is relevant. The objective is to avoid burning fossil fuels, and it doesn’t matter to the atmosphere whether we do so by running the dryer on renewable power, making it more efficient, or not turning it on at all.

It’s a bit like tobacco, another product we burned for a long time before we were aware of the health effects. You might have no hope of giving up cigarettes unless you exercise, meditate, or vape. But doing all of those things, as nice as they might be, will do little to reduce your risk of lung cancer if you still smoke a pack a day.

This irksome fact—that we need to stop consuming still-valuable resources—is what makes the low-carbon energy transition different from previous transitions and coal exits such an important part of EU climate policy.

Coal’s Dying Embers

The good news is coal is on the way out in Europe. In 2019, wind and solar generated more electricity than fossil fuels for the first time ever, as EU-27 power plants burned 339 million tons of coal, down from 586 million tons in 2012. The pandemic-blighted year of 2020 has seen a further drop, with EU coal power generation down nearly a third thanks to a mild winter, low demand during lockdown, and the falling cost of renewables.

Though the trend line is clear, the Europe-wide statistics mask major differences between countries. Sweden, Austria, and Belgium have already closed down their last coal power plants. Coal is increasingly irrelevant for power production in the United Kingdom, Italy, and France, which all plan to quit coal completely over the next few years. Lagging behind are Slovenia, Bulgaria, Greece, and the Czech Republic, which all generate a sizable share of their electricity from coal but do limited damage to the climate because of their relatively small economies.

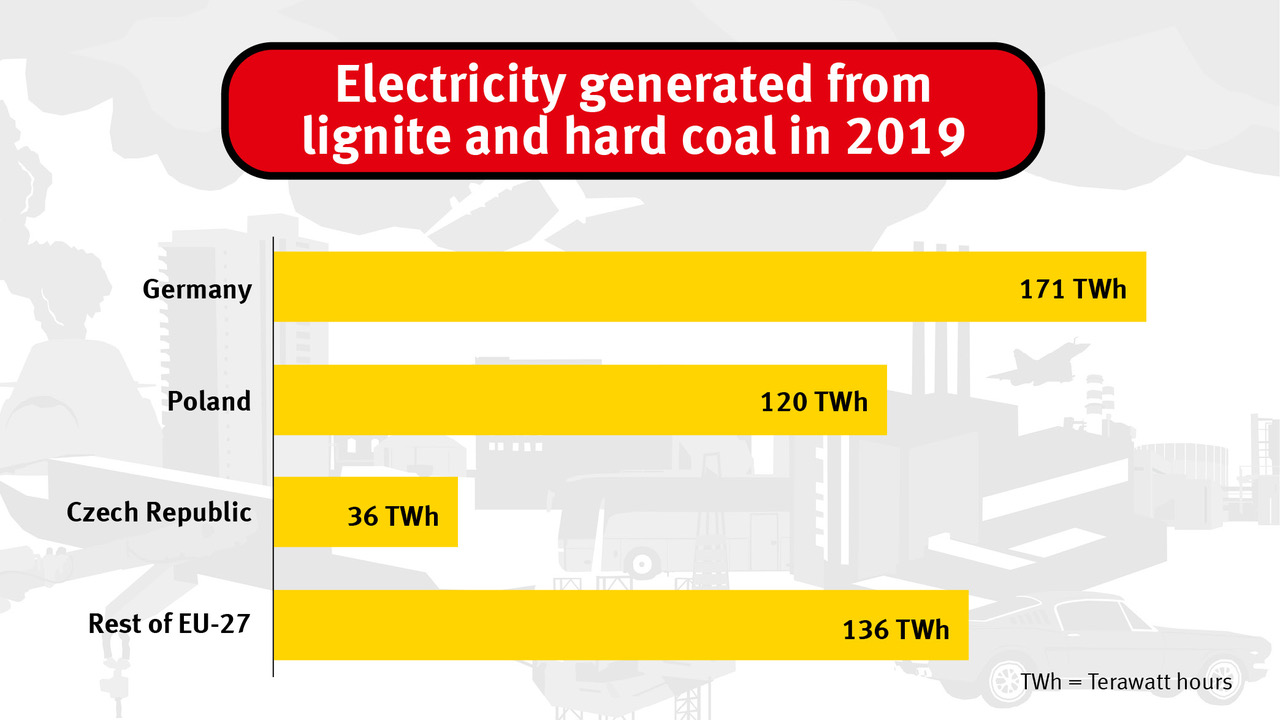

Then there’s Germany and Poland. Each generated about as much electricity from coal as the rest of the EU combined in the first half of 2020, and each plans to burn coal for many years to come.

The Kohleausstieg

In July, Germany adopted a law to ensure the end of coal power by 2038 at the latest. Unfortunately, the Kohleausstieg will happen so slowly that it is incompatible with the Paris Agreement goals—to reach those targets, the German Institute for Economic Research found, Germany would have to quit coal by 2030. Critics also argue that the law will give power companies too much compensation for running coal-fired plants that won’t be profitable anyway.

On the other hand, the process has been a shining example of how to steer and manage the decline of an important industry, with power companies, coal miners and coal regions, and a majority of the Bundestag able to reach a compromise. The €40 billion set aside for coal-dependent regions is a sign that the government realizes the scale of the job. And the coal exit could go faster in the end: the German Federal Network Agency, for one, expects it to be wrapped up by 2035. An expensive date that arrives too late is better than none at all.

Light at the End of the Mine

Poland has set no date for its coal exit. Deputy Prime Minister Jacek Sasin recently said, “We believe that Poland’s dependence on coal energy will come to an end in 2050 or even 2060,” a timeline that makes Germany’s plodding exit look like a hundred-yard dash.

While the nationalist-conservative PiS government is especially close with the coal industry, politics is not the only obstacle to rapid change. Poland is wary of replacing some coal with Russian gas (as Germany has done) and also has no nuclear power plants (a soon-to-be-realized German objective). Ahead of the 2019 parliamentary elections the biggest opposition group, the European Coalition, proposed 2040 as an end date for coal. It appears Poland’s coal replacement will be a slow one, whoever is in charge.

It’s not as if Polish decision-makers are unaware that the future for coal is not bright. The CEO of state-owned coal giant PGG, Tomasz Rogala, admits that “the situation is critical.” The Ministry of State Assets, which Sasin leads, reportedly planned to introduce a restructuring plan for PGG in late July. The plan would have closed several loss-making mines this year, temporarily cut miners’ salaries, created a fund for miners who quit to receive retraining, and perhaps even set a coal exit date of 2036.

In the face of pressure from powerful trade unions, however, the government had to walk back its restructuring plans. (Poland is going ahead with a plan to combine its three utilities in two groups, one for coal and one for non-coal energy, which could pave the way for more changes to come.) It now wants to set up a commission, including union representatives, to find a solution acceptable to all.

Coal miners will benefit from the government’s recent creation of a strategic reserve of hard coal worth €30 million, the latest installment of state support for an industry that has come to rely on it. Polish miners are having to dig deeper and deeper to access coal, which makes it more expensive. In fact, Polish firms have been importing huge quantities of Russian coal because it is cheaper and higher quality, quite a contradiction for a country with such concerns about becoming dependent on energy from the east.

Angry Neighbors

Higher costs for mining, pressure from citizens upset about foul air—in 2016 Poland had 33 of the 50 most polluted cities in Europe—these are the internal forces working against the Polish coal industry. But there is external pressure too, mostly from Brussels. The rising cost of EU emissions permits over the last three years has only added to coal-fired plants’ expenses. And one reason that Polish utilities have risked miners’ fury to import Russian coal is because its sulfur content is low enough to comply with EU regulations, unlike the Polish stuff.

As European climate regulations get stricter and the EU budget gets larger, these external pressures will grow. For instance, according to the EU budget and recovery package agreed last month under Germany’s EU Council presidency, Poland will receive only 50 percent of the funds it is eligible for under the EU’s €17.5 billion Just Transition Fund because it has declined to sign up to the EU goal of net-zero emissions by 2050.

Missing out on a small share of that money, meant for the EU’s most vulnerable fossil fuel-dependent regions, won’t fundamentally change the coal equation for Polish leaders. Yet the fact that the EU is making some funds conditional on climate action (if not adherence to the rule of law) sets a precedent that could be costly for Warsaw. If the EU approves the European Commission’s proposal to increase the 2030 emissions reduction target from 40-55 percent, Poland would have real difficulties meeting its obligations.

Unsatisfying Council Conclusions

By the time of the next EU budget negotiations in 2027, coal will face an even more unfavorable environment. EU politics will be even more Europeanized, perhaps even with transnational lists for European Parliament candidates. The next budget will likely represent a bigger share of member-share revenue and be more conditional on climate action—and pressure from international bodies and trading partners will weigh heavier too.

We could even look ahead to Germany’s next European Council presidency, sometime around 2034. Greta Thunberg will be 31, the next generation of youth climate activists will be even less compromising, and EU consumers will demand more information about the carbon footprint of their products. Poland and Germany, however, will still be burning coal for electricity. Coal may be in decline in Europe, but there is still a lot of work to do to ensure we aren’t having the same debates about coal exits in seven years, or in fourteen.