Donald Trump’s presidency poses a threat to the liberal international order. If Washington abandons its position as guarantor of this world system, are other rich liberal democracies ready to fill the void?

For decades, American leadership has been the most decisive force for the creation and maintenance of the liberal international order. After WW II, the US built an international system that worked to integrate individual states, in particular allies in Europe and Asia. Political and economic cooperation were supposed to replace the great power politics that had pushed the world to the brink of destruction. This postwar order is “liberal” in its very essence: It is based on the conviction that liberal democracy is the only legitimate and, in the long run, stable form of governance – grounded in individual self-determination, which it aspires to bring into a productive, constructive relationship with society. The liberal international order applies the same principle to states: Like individuals, states are seen as self-determined and equal stakeholders whose goals are protection of freedom and promotion of the common good.

At its core, this order depends upon America’s political will to use its immense power for the preservation and further development of the system. And while America has often violated the rules of that system, and its overwhelming power has at times undermined the self-determination it has sought to construct, its allies and partners have tacitly accepted this as the price for the US role as guarantor.

Turning against the Liberal Order

After 1989 it looked as if the liberal order would spread in a self-sustainable way – but the victory was only half complete. China and Russia have, to a large extent, integrated themselves into the US-led economic order, and the elites in both countries are dependent on economic interaction with Western liberal democracies. Yet politically, those same elites have successfully blocked the liberal model.

This puts them into a difficult position: As they oppose a globally accepted norm, they have to find other forms of legitimation. One method consists of control, coercion, and propaganda in an attempt to keep the ideas of liberal democracy at bay. The second approach is to generate prosperity. The Chinese elite has achieved this by betting on economic growth and integration into global value chains. The Russian elite had it easier, profiting from years of high oil and gas prices that supplied a steady income to redistribute, just as in wealthy oil states in the Middle East. A third strategy is aggressive foreign policy. Russian and Chinese leadership claim superiority not just over their own territory, but also over their regions. Both want to turn the concept of spheres of privileged influence into the cornerstone of a new multipolar order – an order in which a few superpowers control regional spaces and everyone else must accept their primacy. Both translate the principle of political order that applies in their states internally – autocracy – into the principle of an international order.

Despite having turned their countries into bulwarks against liberal order, they have failed to translate this rejection into a coherent, attractive alternative. Their growing aggression against neighbors has in many cases led not to the submission of other countries, but to these countries’ increased determination to resist. In both Russia and China’s neighborhoods, smaller, weaker countries have called on the US to provide security guarantees. The more Beijing has abandoned the strategy of “peaceful rise,” the more its neighbors have been alarmed and sought protection. And with the war in Ukraine, Russia has actually seen its influence wane. Resistance against Russia has strengthened Ukraine’s self-defense and given NATO a renewed purpose.

America First, the World Second

The liberal international order has survived until today because it has been supported by key states – and because the US has, since the end of the Cold War, decided to play the role of a guarantor. Yet the domestic arguments for such a far-reaching global role have lost strength over time. There is no clear and present danger to American security anymore. Neither China nor radical Islam has replaced the Soviet Union as a threat that would legitimize, in the eyes of American voters, America’s extensive and expensive commitment to global security.

Pressure on the American government to scale down global commitment has grown in recent years, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have only fed this groundswell of discontent.

And yet America has until now hesitated to abandon its role as a guarantor of the liberal international order. The US has enjoyed plenty of comparative advantages as this order’s architect and central force, and it is far from clear what will happen if Washington retreats significantly. Will this order implode, with disastrous consequences for regions that the US considers to be strategically important?

Such considerations made Obama – who swept into power on the promise of reducing America’s role abroad – hesitate. He was pulled back and forth between those in his team who wanted to maintain the expansive global engagement and those who wanted a break with the status quo.

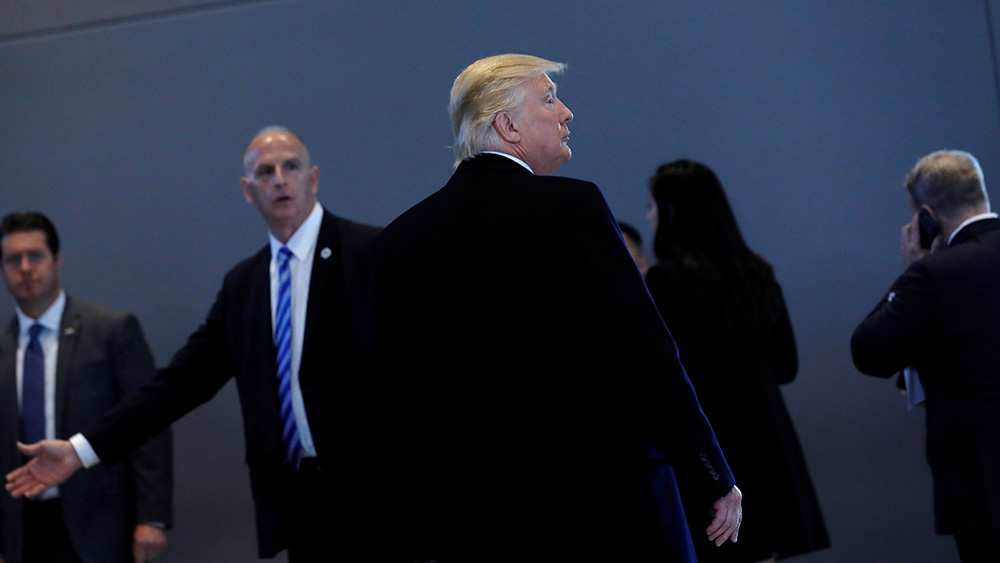

Unlike Obama, President Trump has displayed no understanding of America’s role abroad. Instead, he seems keen to strengthen borders and to limit exchange and global engagement. For him, America must be protected against immigrants from Mexico, against economic competition from China, against terrorists from Syria. Allies and partners are a costly burden, international institutions mostly useless; what matters are transactional deals. “Americanism, not globalism, is our credo,” he has said during the campaign.

The consequences of Trump’s rhetoric are still unclear: How much of it will translate into policy? How strong are the counterbalancing forces – in his own government, in Congress? In any case, by electing a president with an anti-internationalist agenda, American voters have given another indication that they feel increasingly uneasy about their role in the world. They refused a candidate, Hillary Clinton, who stood for continuity, and that includes America’s role as the guarantor of the liberal international order.

If Not America, Who?

The question of what follows the American-led order is becoming ever more pressing. If the US abandons its role as guarantor, is the current order going to disintegrate? Or are there other actors who could at least partially take over?

It has become increasingly clear that neither Russia nor China is a candidate for such a role. Quite the opposite: Ruling elites in both countries are hostile to key parts of the liberal international order because it threatens to undermine their autocratic power at home. Moscow and Beijing share a concept of international order that is based on dominance and submission, a multipolar world with a few great powers that divide and rule according to their needs. Both have an interest in keeping the international economic order at least partly intact, but both are hostile to the overall character of an order based on freedom, equality and rule of law.

Instead, the B team must step in: Those liberal democracies that have an existential interest in maintaining the liberal order and are able, given their economic power, to play in the top league, must rise to the challenge. There are quite a few candidates for such a role. Among the world’s economically strongest 15 countries, there are no less than twelve other liberal democracies besides the US – Japan, Germany, Britain, France, India, Italy, Brazil, Canada, Korea, Australia, Spain, and Mexico (in order of GDP, according to IMF, October 2016).

All twelve are allies and partners of the US, and all have profited massively from the US-guaranteed international order. Together they have a GDP of $25,739 trillion, more than the US ($18,561) and more than China ($11,391) and Russia ($1,267) combined ($12,658). Five of them are European: Germany, Britain, France, Italy, and Spain (a combined GDP of $11,735); four are Pacific countries: Japan, India, Korea, Australia ($9,640); two are Latin American: Brazil and Mexico ($2,832); and one is North American: Canada ($1,532).

In order to transform themselves collectively into guardians of the liberal international order, the twelve would have to do at least five things:

First, they would have to pursue far more active foreign policies, based on a self-understanding as an important global force. The twelve would have to see themselves as guarantors of the institutional framework and the material infrastructure of globalization. This would also have a military dimension. They should be able to largely guarantee their own security and to provide protection to smaller countries. To achieve these goals, existing alliances could serve as platforms.

Next, they would have to recognize that their interest does not lie in the multipolar order that Russia and China are trying to advance, and they would have to be ready to confront Russia and China whenever they threaten the liberal international order.

The twelve would also have to build more interconnectivity and networks; they should be able to pursue goals without Washington when needed. They should conclude true strategic partnerships among themselves, oriented toward joint regional and global strategies. An annual summit could provide one such format.

The twelve should also aim to provide more leadership in their respective regions and bring smaller, like-minded liberal democracies on board to stabilize the liberal international order as a way to gain more weight and critical mass. Regional organizations such as the EU or ASEAN could serve as vehicles.

Finally, the twelve would have to accept that their own long-term security, liberty, and prosperity depend on the fact that other countries are governed in a democratic way. The liberal international order is based on the preeminence of liberal democracy at the national level. Strengthening democracies and supporting countries in their transformation from autocracy to democracy are therefore key common interests of these twelve states; a liberal international order can only exist if there is a critical mass of powerful liberal democracies.

The US remains the “indispensable power” in many regards. But Washington might further retreat in the coming years from its role as a guarantor of the liberal international order. The countries that have in the past profited from this order are confronted with a tough choice: either engage massively on behalf of it and rise to the challenge as the B team, or accept its decline or implosion.