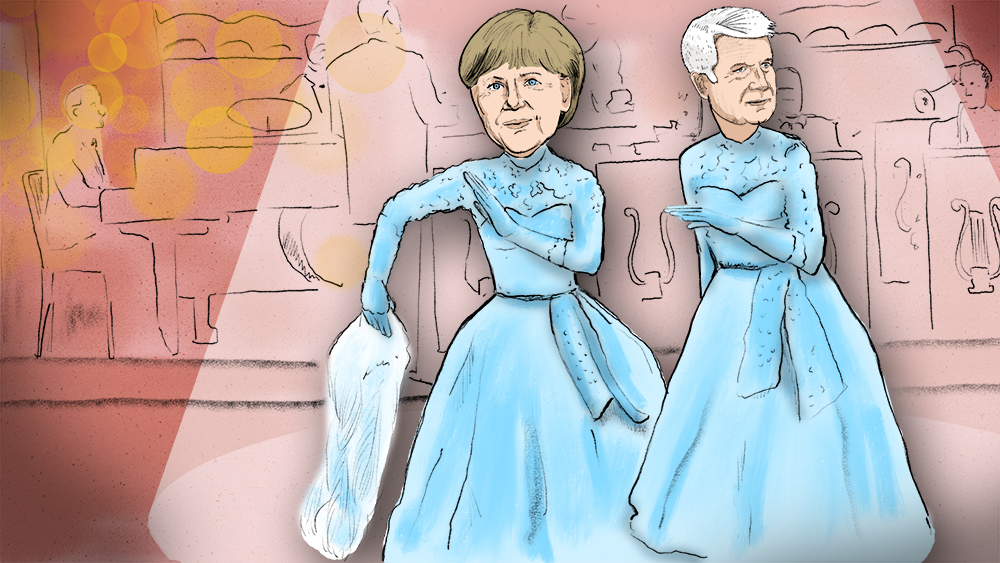

The aging sisters of German politics, Angela Merkel’s CDU and its Bavarian sibling CSU, have always been more devoted to power than each other.

“Sisters, sisters/There were never such devoted sisters…”

When US songwriter Irving Berlin penned his ironic ode to the joys of sisterhood for the 1954 movie “White Christmas,” Germany’s most famous political sisters were already nine years old.

The Christian Democratic Union (CDU) was founded just a month after Nazi Germany’s capitulation in May 1945, with Bavaria’s Christian Social Union (CSU) following four months later. The war-shattered country would be under direct Allied occupation for years to come, but the CDU/CSU were confident they could become the future Germany’s dominant political force.

Pitching themselves as non-denominational, center-right catch-all parties, heirs to defunct old center parties and an alternative to the working class Social Democrats (SPD), the CDU and CSU formed a parliamentary alliance in 1948, with the foundation of the (West) German federal republic just months away. The Munich-based CSU agreed to focus on the largely agrarian southern state of Bavaria while the CDU took the rest of the West Germany.

This deal, renewed at the start of every new parliamentary session, joins a CDU parliamentary party head with a CSU politician deputy. It gives the Bavarians considerable political clout far beyond their state borders where the CSU has governed continuously for half a century, mostly alone.

“Two different faces, but in tight places/We think and we act as one”

Their pact is based on common political interests and the promise “never to stand in competition in any federal state.” It has allowed the CDU/CSU meet their ambition to dominate West German politics. From the first chancellor Konrad Adenauer to Angela Merkel today, the CDU/CSU has provided the chancellor for all but 20 years of the last seven decades.

Despite shared principles and goals, both parties “adhere to the basic principle that each (parliamentary party) is a group of parliamentarians of their respective, independent parties.”

This allows the CSU, should it wish, to vote against the CDU “in a question of particular importance.” But, to minimize potential for political chaos or blackmail, fundamental decisions only come onto the agenda “through consent of both groups.” The CSU is famous for having a bark far worse than its bite, but decades of practice at barking can make it an uncomfortable and unpredictable sister.

“Those who’ve seen us/Know that not a thing could come between us”

By and large the CDU/CSU agreement has held, but not without testing episodes. The biggest drama came 42 years ago in Kreuth, a picturesque resort town in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps and for years the location of the CSU’s winter retreat.

After the 1976 federal election, the legendary CSU leader Franz-Josef Strauss attacked his CDU ally Helmut Kohl as “political pygmy.” Strauss was furious because the CDU/CSU won the election but still failed to unseat the SPD alliance with the liberal Free Democrats (FPD).

Talking himself into a state, Strauss suggested the CDU was more political ballast than a boost and mulled pushing beyond Bavaria’s borders as a fourth national political force.

His threat to end the CDU/CSU alliance met with considerable resistance inside his own party and prompted a counter-threat from the CDU to launch a party in Bavaria. Eventually Strauss blinked, and the sisterhood survived.

“Never had to have a chaperone, no sir/I’m there to keep my eye on her”

The latest challenge to the sisterhood began to build after the 2015/2016 refugee crisis brought over a million people into the country, accentuating the CDU/CSU political and cultural differences. The Bavarians, on the front lines of the crisis, demanded a more robust line from Berlin. But CDU leader Angela Merkel followed a more liberal, open-border policy while she pressed for an EU burden-sharing agreement for migrants. After a tense standoff, the Bavarians fell into line for last year’s federal election. But not before CSU leader Horst Seehofer accused her of operating an “unlawful regime” on migration and gave her a humiliating dressing down at his party conference.

After disastrous election results last year, the migration row flared up again this summer. With his CSU facing a state election disaster in October, Seehofer and his party ramped up tough talk on migration to impress law-and-order voters. Seehofer, who is also federal interior minister in Berlin, threatened to unilaterally close off the German (i.e. Bavarian) border to Austria to refugees already registered elsewhere in the EU—and even to resign—unless Merkel achieved a European agreement to throttle immigration.

It was a high-risk move because making good on his threat would have blown up the CDU/CSU alliance. In the end, Chancellor Merkel returned from an all-night Brussels summit with political concessions.

“All kinds of weather, we stick together/The same in the rain or sun”

Whether that is enough to appease CSU voters—and avoid another family squabble—will only become clear when the Bavarian state election results come in on October 14.

Now aged 73, with no other eligible suitors, the aging sisters of German politics have always been more devoted to power than each other. But they hide it well, presenting themselves as living proof that sibling rivalry may not be easy, but need not be fatal.