After 13 years in power, Angela Merkel’s authority is crumbling. Her Bavarian sister party looks set to take a beating in the upcoming regional elections. She needs to act quickly if she wants to remain in power.

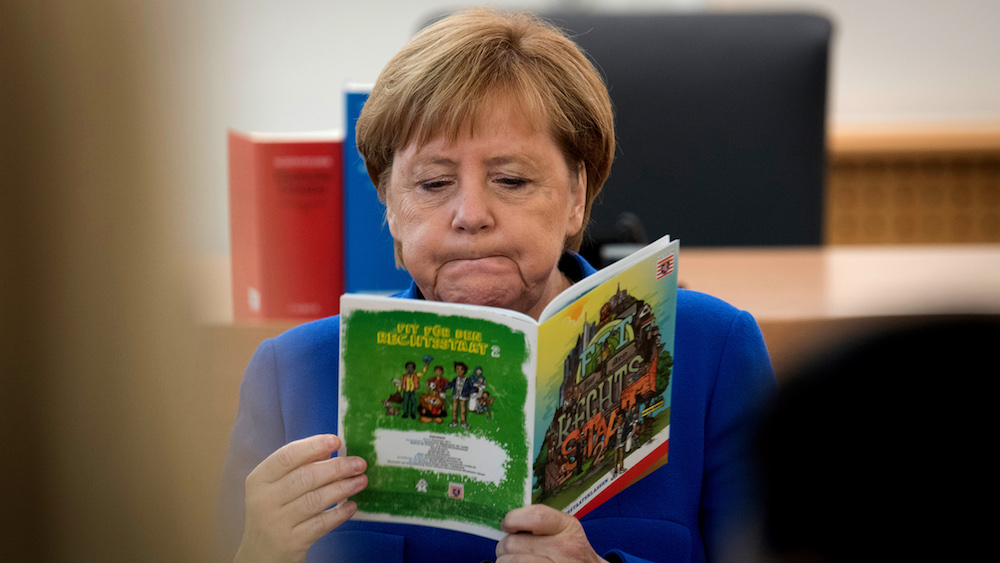

Over the coming weeks, German chancellor Angela Merkel will need to reinvent herself. Against her sober, cautious nature, she will have to reach out to the public to explain her vision of Germany’s future. She will have to draw the big picture and appeal to people’s emotions as well as their common sense. In other words: she needs to re-establish trust in her leadership to rally the public around her faltering chancellorship.

Does she have it in her? Doubts are in order. A leopard does not change its spots, and Merkel doesn’t believe in visions. Also, she has never been an orator who is able—or even aspires—to play on an audience’s emotions. After 13 years in office, she is immensely experienced but also quite tired. Ambition has been replaced by duty, and while a sense of duty is a powerful motive, it is not a good driver for a personality makeover.

Yet nothing less than Merkel’s leadership is at stake. On October 14, a regional election will take place in the state of Bavaria; two weeks later, the state of Hesse follows. Her conservative bloc is expected to suffer losses, and part of the blame is certain to be laid at her door.

At the same time, the election in Bavaria, in particular, offers some hope of a new start for Merkel. There, it is not her own party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), which is standing, but its more right-wing “sister party,” the Christian Social Union (CSU).

The CSU has governed Bavaria with an absolute majority for nearly all of the past 60 years, but this time, polls say, it will only be getting between 33 and 35 percent of the votes. Of course, the blame game has already started, and one culprit has already been identified: Horst Seehofer, head of the CSU and interior minister in the federal government in Berlin.

Troublemaker Seehofer

Twice over the past four months, Seehofer nearly brought down Merkel’s coalition—out of personal resentment against the chancellor, because he was opposed to her open-door policy for refugees from the beginning, and because he thought that a hard stance in Berlin would benefit the CSU at the polls.

Like in the Greek myths, however, the doom that Seehofer had been trying to avoid is coming down on him all the harder. Bavarians did not appreciate Seehofer’s brinkmanship, and the Catholic wing of his CSU did not approve of the way he instrumentalized the refugee issue. Short of a miracle, Seehofer will have to step down as party leader of the CSU on Sunday. That means that Merkel may also be able to get rid of him as interior minister.

With new personnel and some clear words about her overall strategy and goals, Merkel could try to re-launch her government. It may be her last chance to do so—even within her own party, her authority is crumbling.

At the end of September, her CDU/CSU Bundestag caucus went against her wishes and voted in a surprise candidate as group leader. Ralph Brinkhaus, a finance expert virtually unknown outside the corridors of the Bundestag, replaced Volker Kauder who had been Merkel’s very close aide and confidant for nearly 20 years.

Ever since, Merkel’s critics are growing bolder. One of them is Norbert Röttgen, head of the foreign affairs committee in the Bundestag, whom Merkel fired as environment minister back in 2012. In a well-publicized interview, Röttgen spoke about a systemic crisis in Germany that would worsen if Merkel did not change her approach. He also proposed putting a limit on the chancellor’s term of office—not exactly a subtle hint.

The End of Merkel?

Merkel has repeatedly confirmed that she wishes to remain chancellor for a full fourth term until 2021, and she has also made it clear that she believes the party chairmanship and the chancellery go hand in hand. This makes the CDU’s party congress in early December crunch time for Merkel, as delegates will vote on their leadership. Should they decide not to renew Merkel’s mandate as CDU chairwoman, it is hard to see how she could remain chancellor.

So far, it appears unlikely that Merkel will be replaced. Two Christian Democratic politicians have announced their candidature for the party chairmanship, but both are nobodies who aren’t considered to stand any chance at all.

More credible competitors are still hesitant about entering the race. For Merkel, the most dangerous is Jens Spahn, who serves as health minister in her coalition. Spahn, who (unusually) recently visited US national security advisor John Bolton in Washington, is very popular with the more conservative part of the party base and he has always made clear that he wants to become chancellor one day.

How will this play out? Most probably, Merkel can still pull it together, if she puts her mind to it. But the congress of the Junge Union, the youth organization of CDU and CSU, last weekend offered a taste of a different future. Merkel received good applause for a good speech. But Spahn, calling out for “a patriotism in keeping with our time,” was feted with standing ovations.