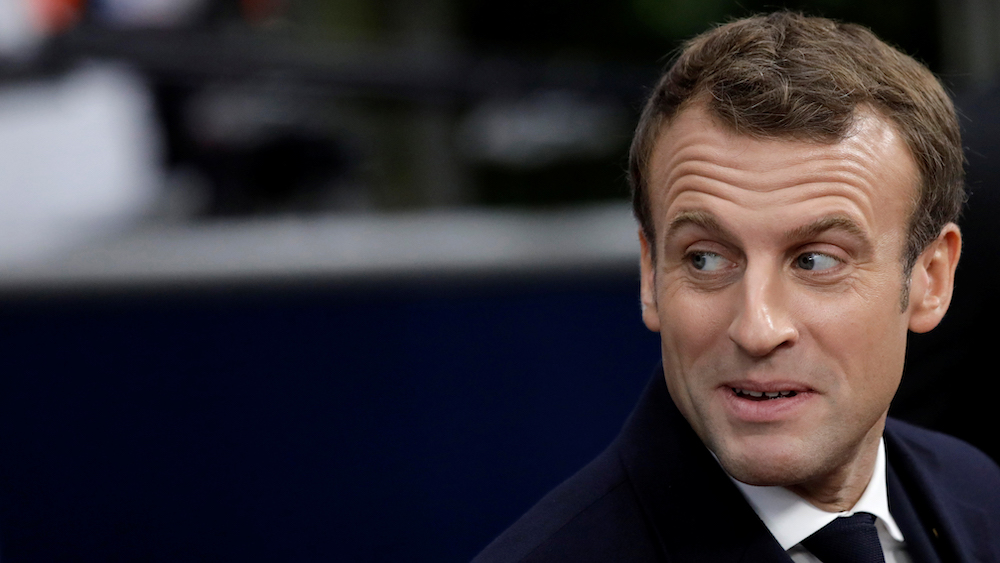

French President Emmanuel Macron has been very active on the world stage lately. To succeed, he will need to strike a difficult balance between national self-assertion and EU integration.

Since the summer, Emmanuel Macron has made a sudden reappearance on the front lines of international politics. In August, he invited Vladimir Putin to Fort de Brégançon, the French presidential retreat, where the two leaders discussed the conflict in Ukraine and the possibility of Russia’s readmission to the G7 economic summit. Later that month, as G7 host, Macron welcomed leaders of the world’s largest industrial nations, but also brought along a surprise guest, Iran’s foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif.

At the United Nations in September, the French president called on his fellow world leaders to show “the courage of responsibility.” This prompts the question: is Macron is speaking here on behalf of France or of the European Union as a whole, and can the two positions be reconciled?

A Sense of Urgency

Political observers in the French capital agree on this: Europe’s security architecture is under threat to a degree not seen in three or even four decades. In Macron’s own words: “The international order is being disrupted in an unprecedented way…for the first time in our history, in almost all areas and on a historic scale. Above all, there is a transformation, a geopolitical and strategic reconfiguration.” The French president was referring to the challenge to multilateralism from great powers like the United States and China, but also to intensifying armed conflicts close to Europe’s frontiers. Yet another worry for Macron is the distance the Trump administration has taken from questions of European security.

Macron believes the world now emerging will have a bipolar structure, with the United States on one side and China on the other. All other states will play a subordinate role; this includes Russia, which faces marginalization within this new bipolar order. For Europe, the outlook is little better: “We will have to choose between the two dominant powers,” he told the conference of French ambassadors in August. In other words, the choice open to a future Europe will be whom to serve as junior partner.

But Macron would not be Macron if he gave up in the face of adversity. Having made his bleak assessment, he concluded by demanding that Europe turn itself into an autonomous international actor. As outlined in his famous 2017 Sorbonne speech, Macron wants to see the construction of a sovereign Europe. This Europe would be able to live according to its own values (by no means identical to American values), safeguard its own political and economic interests, and, not least, defend itself militarily. For Macron, this is a matter of urgency.

A Common Front with Russia

France’s desire to improve relations with Russia should be seen against this backdrop. Macron is well aware of Moscow’s hostile stance toward the EU, but he continues to push for constructive cooperation in the relatively near future, for example on arms control and in space. The aim is to prevent Russia from further destabilizing the EU and its surrounding regions. Macron also has another goal in mind: he ultimately sees Russia as a possible ally for Europe in the emerging bipolar world system.

At the conference of ambassadors, Macron was explicit: “To rebuild a real European project in a world that is at risk of bipolarization, [we must] succeed at forming a common front between the EU and Russia.” The statement provoked anger, and not only among EU member states in Eastern Europe, where many fear that closer ties to Moscow inevitably spell danger. There is also a distinct air of skepticism among French political and diplomatic elites. Macron is well aware of this, hence his insistence that French ambassadors adopt a new and different mentality.

This is Macron’s vision of the future. But present-day realities look somewhat different. For a number of years, Islamist terror attacks have been a pressing, immediate danger to France. It is clear that the French government can only win out in the battle against terrorism through cooperation with partners and allies. The same goes for overseas military operations, where France rapidly comes up against the limits of its own power.

This explains French pragmatism on the question of allies. “We need to find support everywhere we can,” Defense Minister Florence Parly told a conference at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington in 2017. In this respect, the US remains indispensable to France. Particularly in the Sahel region of West Africa, France relies on Washington for logistical support and intelligence sharing. Considerable flexibility is needed to combine that sort of dependency with France’s aspirations to autonomy. All the more so when dealing with an unpredictable interlocutor like Donald Trump.

Disappointed with Berlin

Macron’s new foreign policy may seek to invoke the independent French position of previous presidents Charles de Gaulle and Jacques Chirac. However, the current president has added a new element to traditional Fifth Republic foreign policy. No president prior to Macron has ever made such a clear push for European integration, including foreign and security policy. This has particular relevance to the question of autonomy, something Macron desires both for France and for Europe. French policy elites still regard the EU as a force multiplier, useful for a country now without the capacities to match its ambition, despite its nuclear weapons and its permanent UN Security Council seat. But France also regards the EU as a community of interests that must present a united front in an increasingly turbulent world. For this reason, goes the argument, the EU must develop its capacities to operate autonomously in the long term, if necessary without its traditional American partner.

Immediately after his election, Macron attempted to achieve this through close cooperation on fiscal and monetary policy with Germany. However, it rapidly became clear that Berlin had no intention of supporting his ambitious projects for the eurozone. For Paris, this German reluctance increased the importance of another aspect of bilateral relations: defense and arms industry cooperation. The Aachen Treaty, signed by the two countries in January 2019, committed them to “continue to intensify the cooperation between their armed forces with a view to the establishment of a common culture and joint deployments.”

Paris has now distinctly lowered its expectations of a grand alliance with Berlin. In any case, an arrangement like that can only be a project for the very long term. One recent move can been seen as a small first step. The Franco-German agreement at the countries’ most recent bilateral talks in Toulouse makes important changes to arms export regulation. Crucially, Germany will no longer claim the right to block exports of jointly-manufactured weapons systems if German components make up less than 20 percent of the arms in question.

In practice, however, Franco-German cooperation continues to occupy precarious political ground, not least because of stark differences in foreign policy traditions. This is why Paris has sought British participation in European security policy instruments, including the recently established European Intervention Initiative, a 13-nation military project outside both the EU and NATO. Brexit or no Brexit, the United Kingdom and France share a particular strategic outlook, as well as a long tradition of overseas military intervention. In this context, Britain will remain an important partner for France.

A Change of Strategy

Growing frustrations, above all the disappointment with Berlin, led Macron to change his European strategy ahead of May’s European elections. First, Paris now no longer shied away from confrontation with Berlin. Second, the French government intensified its involvement in EU institutional politics and wants to use this more strongly as leverage. Macron supported the formation of Renew Europe, a new liberal grouping in the European parliament, in which French parliamentarians are the biggest delegation (21 out of 74).

Macron also robustly intervened in the struggle over key EU leadership posts. He actively opposed the so-called Spitzenkandidat (“lead candidate”) system, by which the winning party in European parliamentary elections could claim the presidency of the European Commission. Instead, Macron backed Ursula von der Leyen for president. He was gratified that her Europe Agenda 2019–2024 borrowed key ideas from his Sorbonne speech, including ambitious climate goals, a European minimum wage, and the creation of an EU defense union. The French president also pushed for the appointment of Charles Michel as European Council president and Josep Borrell as the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. In Paris, both men are regarded as close to French positions.

Macron’s final tactical maneuver would have seen Sylvie Goulard appointed as a commissioner in charge of a beefed-up portfolio including internal market affairs, as well as industry, aerospace, digitization and culture. Goulard would have overseen the implementation of Macron’s preferred EU projects. But the European parliament rejected Goulard’s nomination, a severe blow to Macron.

In picking Thierry Breton, a businessman and one-time French Minister for Economy, Finance and Industry, as a substitute for Goulard, Macron signaled that knowledge of Germany and therefore the ability to explain his project to the Germans (which Goulard had) was no longer a requirement for the job. The top priority is now to maintain the portfolio that Paris had negotiated and which is in line with its European agenda. A top-level partnership between Goulard and von der Leyen could have been a dynamic driving force for Franco-German cooperation at the EU level. This is now a more difficult proposition, particularly since von der Leyen’s own position has turned out to be more fragile than expected, while the European Parliament seems set to remain riven by political tensions.

Difficult Road to Europeanization

In Paris, the unexpected obstacles in Brussels have been the cause of even more frustration. This French impatience is prompted by the general sense of urgency, along with the country’s aspirations to leadership. In response, the Macron administration has sought room for maneuver elsewhere, going beyond EU frameworks and other traditional diplomatic formats.

The recent rapprochement with Russia is a case in point. Paris will do what it regards as right for both itself and the EU, although where interests actually overlap is a matter for debate. France also hopes its actions will persuade other partners to get on board: French foreign policy is meant to be inclusive. The talks with Putin, for example, were regarded in Paris as a first step, to be followed by the continuation of the “Normandy format” Ukrainian peace talks, which also involved Germany and Ukraine. However, such solo activism may run the risk of offending France’s EU partners, fomenting unnecessary trouble.

One example of this was France’s recent veto of Albania’s and North Macedonia’s application to join the EU, in what would have been a further expansion, this time into south-eastern Europe. Macron’s arguments on the subject are actually entirely legitimate. He is quite right to suggest that the EU’s accession process is problematic: the prospective new members gave inadequate assurances on the rule of law, where improvements are clearly required. Moreover, it is doubtful whether the EU, already embroiled in a painful Brexit saga, would be prepared to admit new members before it has reformed its own institutions and internal processes.

Macron’s veto was meant to signal that expansion would endanger integration, risking the EU’s cohesion and unity. Here, he continued a long-standing tradition in France’s European policy that regards deepening and enlargement as mutually contradictory. Opponents of Macron’s position argue that the EU’s borders should be stabilized, demanding a more pragmatic approach. The French president understands this objection. However, he has maintained his veto, which has come at a high price. The issue has seen him isolated, and has weakened his pro-European credibility.

Be Patient, Be Polite

For all his pro-European convictions, Macron has no intention of silencing France’s voice on the world stage. Like all French politicians, he is not prepared to hand over the country’s permanent UN Security Council seat to an EU representative. At best, Macron may coordinate policy with other European members of the Security Council, thus fulfilling the Aachen Treaty’s stipulation that France and Germany should act “in accordance with the positions and interests of the European Union.”

Given this logic, it is unsurprising that Macron welcomed Borrell’s appointment as High Representative. Borrell is familiar with France’s strategic culture, but also with the sensitivities of member states that are jealous of their prerogatives, the result of many years serving as Spanish foreign minister. He realizes it would be an error to seek the limelight. Of course, he will set the tone for his own department, but his main focus will be on internal coordination processes. All foreign affairs issues will probably be discussed in the Council of Ministers, where larger states tend to have greater visibility. Nonetheless, the EU needs unity in order, for example, to impose economic sanctions as a foreign policy instrument. The voices of the larger states only dominate if the entire EU goes along with them and implements their decisions. This interplay of forces will determine what happens.

For Macron this means that he must constantly strike a balance between national self-assertion and integration within EU structures. If he wants to exert influence within the EU, he cannot go it alone. That’s no easy task for a man of Macron’s impatience. Here, he runs a twofold risk: first, he may offend his partners and come across as arrogant, especially to smaller EU states, who feel he patronizes them. The second risk is that Macron will lose credibility if his well-publicized plans end up going nowhere. In both cases, it is a question of reliability and trust, a basic requirement if the project of European autonomy is to gain sustainable momentum.