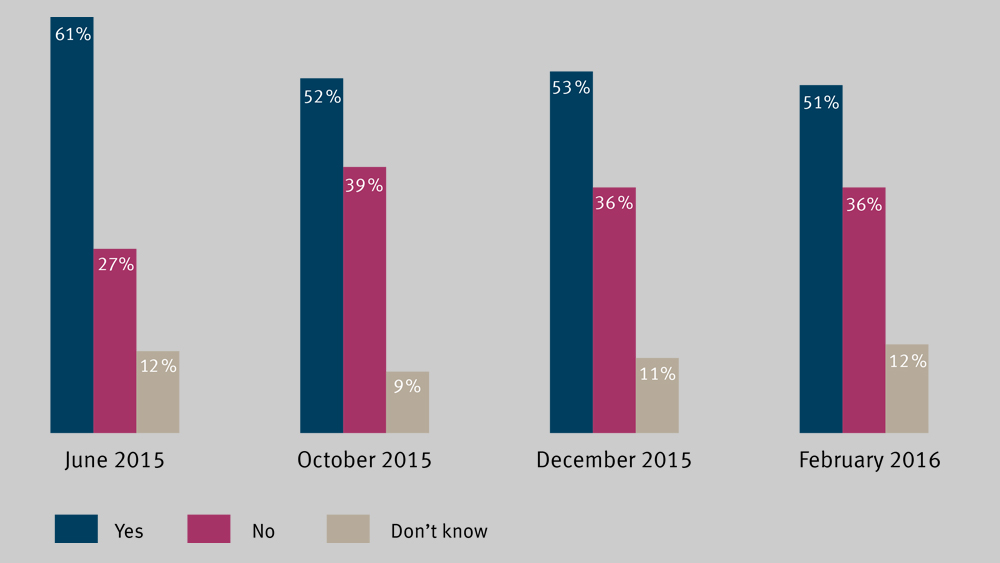

Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the EU?

For those who would prefer to see the United Kingdom remain in the European Union, some recent poll numbers have not exactly been encouraging: a dramatic YouGov poll released in early February showed a growing plurality (45 percent) in favor of a so-called Brexit, compared to a smaller minority (36 percent) who wished to remain. After the EU summit on February 17-18, when a special deal for UK was hammered out, and after Prime Minister David Cameron called the “in-out” referendum for June 23, another YouGov poll saw that margin closed again, with 38 percent in favor of leaving and 37 percent wanting to remain a EU member state.Figures from UK pollsters IPSOS-Mori, meanwhile, suggest that the race is not as close: Asked the official referendum question between February 13-16 (“Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”), 54 percent opted for “remain”, with 36 percent stating they wanted to leave. Still, the figures for the “don’t knows” are substantial. And, as the 2014 ballot on Scottish independence showed, the outcome of referenda is sometimes tricky to predict.

One “wild card” factor is Europe’s continuing refugee crisis, with Britons worried about the security of their borders (and, whether justified or not, the sustainability of their social welfare structures); and the concessions Cameron negotiated with European Council President Donald Tusk, underwritten by the February EU summit, have failed to assuage concerns, with a quarter of Britons saying they “[do] not have the makings of a good deal,” nearly 50 percent saying “it has the makings of a reasonable deal yet to come” (“damning with faint praise” doesn’t quite do it) – and 15 percent calling them an “insult”. The number of Britons calling the deal “pretty good” fell nearly within the survey’s margin of error.

Will Britain leave the EU? It is not impossible. But with a couple of months to go before a referendum, Cameron – whose biggest fight to keep Britain in is with his own Conservative party and the press – has time to maneuver and levers to pull. (Germans, meanwhile, displaying tinged Teutonic positivism, said that they would prefer Britain remain part of the EU – 59 percent – but that it was more likely than not that Britain would leave. Whether this was said while picking off the petals of a daisy remains unknown.)

There is, however, an even more immediate threat to European unity. As far back as August 2015 – that is, when the refugee crisis was still discussed as a problem facing Calais and its notorious “jungle” camps – majorities throughout Europe already supported the reintroduction of border controls: two-thirds in France and the UK and over half in the Netherlands, Italy, and Germany expressed a desire to suspend the Schengen agreement which allows for passport-free travel within continental Europe; Britain and Ireland opted not to join. Since then, those numbers have in many cases increased. In January, ARD DeutschlandTREND found that 57 percent of Germans supported re-instituting border controls within the EU (in a YouGov poll, the number was 77 percent).

The fall of Schengen would deal grave damage to the union as a whole. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble warned that, should the Schengen agreement collapse, the EU would be in “tremendous danger” both politically and economically. European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has been no less clear in his assessment, saying that, “If anyone wants to kill off Schengen, ultimately what they would do is do away with the single market as well.”

Are their fears justified? Schäuble and Juncker are concerned about the economic repercussions of the end of free movement within the EU, but the risks such an abrogation would pose actually go deeper than that. In its spring 2015 survey, Eurobarometer asked Europeans what the most positive result of European integration had been. “The free movement of people, goods, and services within the EU” took the top spot with 57 percent – somewhat ironic given the aforementioned number of Germans, and Europeans overall, wanting to bring back passport controls. This was followed closely by “Peace among the member states of the EU” with 55 percent.

That “free movement” edged out “avoiding war” is no fluke. In the German Marshall Fund’s 2014 Transatlantic Trends survey, pluralities listed “freedom of travel, work, and study within [the EU’s] borders” as the most important argument for EU membership in the UK, Portugal, Poland, and Greece; German and French respondents were, perhaps understandably, more likely to value the EU for its ability to keep the peace in Europe, along with the fact that it represented “a community of democracies that should act together.”

And even in these countries, younger respondents – those who have not known an EU without Schengen – think the EU is synonymous with mobility: a plurality (32 percent) of Germans aged 18-24 who thought Germany’s EU membership was a good thing listed free travel as its most important benefit, as did a plurality of young French respondents (40 percent).

Put simply: many Europeans – especially those who have not been Europeans for long, whether because of age or nationality – equate European identity with European mobility. Remove the latter and there is a risk of seriously undermining enthusiasm for the former, at a time when such malaise can hardly be afforded.

Read more in the Berlin Policy Journal App – March/April 2016 issue.