A Forsa survey conducted for our German-language sister publication Internationale Politik in February produced a result that basically confirmed earlier polls: a fairly wide plurality of Germans (46 percent) consider the rise of “Asian countries” an opportunity, while only a third (33 percent) consider it a threat. This mirrors findings from other surveys over the past few years: Growing numbers of Europeans, especially Germans, have been describing China more positively, seeing it more as a potential partner than a potential competitor.

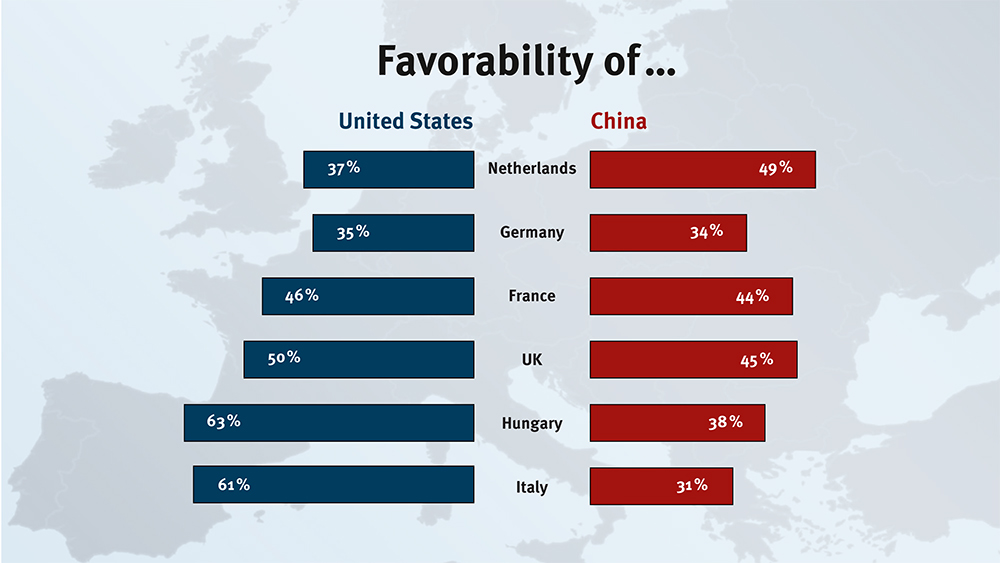

In a Pew Research Center global attitudes survey conducted in spring 2017, the United States and China were neck and neck in terms of favorability, with China more popular in the Netherlands and Spain and just about tied with Germany, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. A fifth of Germans (21 percent) described “China’s power and influence” as a threat – but then, a third said the same of the US (35 percent).

And as far back as 2013, the German Marshall Fund’s Transatlantic Trends survey showed a transatlantic divide on the issue: While almost two thirds of Americans viewed China as a threat, Europeans were nearly evenly divided, with Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK more likely to see China as an opportunity and France, Italy, Poland, Portugal, and Spain more likely to see it as a threat.

Are Germans simply more optimistic? That seems unlikely.

Two things are important to establish when looking at survey data on Asia in general or China in particular (and it’s worth noting that the two often serve as proxies for each other in survey questions—ask about Asia and your respondent will likely think of China).

First, even the people who view the rise of China as an opportunity haven’t necessarily liked it that much. In the same Transatlantic Trends survey, 60 percent of Europeans—including 71 percent of Germans and 65 percent of Swedes—said their opinion of China was “unfavorable,” and 65 percent of Europeans described a strong international leadership role for China as “undesirable.” The more recent Pew poll shows that people have warmed up to China since then, but it should be clear that seeing China as an economic opportunity does not necessarily correlate with seeing it as a friend.

Second, demographics matter. A closer examination of the Forsa poll reveals two details worth examining. First, there is a significant education divide between Germans who view China as an opportunity and Germans who view China as a threat: 51 percent of Germans who studied beyond high school see China as an opportunity, compared to only 40 percent of those who did not study beyond high school and 31 percent who attended the less prestigious Hauptschule. In other words, the more educated a German is, the more likely he or she is to see China as an opportunity.

Second, there is no clear difference between the responses given by Germans from different political backgrounds. A supporter of Merkel’s CDU was just as likely (allowing for a 3 percent margin of error) to see China as an opportunity as a supporter of the center-left SPD, and even the outliers—the Greens at 57 percent and the FDP at 47 percent—were not that far apart. The only exception is the right-wing populist Alternative für Deutschland: AfD voters were considerably more likely to see China as a threat, and considerably less likely to see it as an opportunity.

What does this mean? Voters from very different parties with very different ideas regarding international trade held basically similar views regarding the economic rise of Asia.

Here’s one possible explanation for these attitudes: China has become such a political symbol in both the US and Europe—a stand-in for foreign competition, and globalization in general—that questions about China elicit answers about economic security. If a European is asked how they feel about the rise of China (or Asian nations in general), they will answer by estimating their own likelihood of being displaced—an educated German whose job is reasonably secure will see China as an opportunity, while a less educated German (or a French or Spanish respondent) with an uncertain economic future will see China as yet another competitor in the workplace.

These respondents would be hard-pressed to name any of China’s policies, or indeed to point to the sectors where it offered either a threat or an opportunity. But they know how relatively precarious their own economic positions are, and how likely any new factor is to be one or the other. In other words, when we ask about China, we are really asking: How prepared do you feel for competition?