Europe’s relationship with Turkey has certainly not been easy over the past few years. As the Turkish government under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has drifted further and further away from liberal, secular democracy, it has become harder to cooperate on matters of regional security and economic policy without appearing to endorse policies that run counter to fundamental values of the European Union. Meanwhile, from Turkey’s point of view, the EU has been a capricious and unreliable partner, its interest in the country’s eventual accession seeming to wax and wane according to its needs.

A series of recent spats – including the Jan Böhmermann affair, in which the Turkish president pressed legal charges against a German satirist over a lurid parody poem – have strained the relationship even further, and domestic developments within Turkey, especially the 2013 Gezi Park protests and the recent coup attempt and its aftermath, have called the country’s internal stability into serious question. And of course, all of this is happening at a time when the EU needs Turkey more than it has in decades: the continuing civil war in Syria and the resulting refugee crisis, along with the threat posed by the so-called Islamic State, have made Turkey Europe’s indispensable partner, a state of affairs Erdogan has used to push for greater economic integration and relaxed visa requirements for Turkish citizens.

When, back in 2007, the German Marshall Fund’s Transatlantic Trends poll asked whether Turkey’s becoming a member of the EU was likely or unlikely and what effect it would have on the union, a majority of Europeans said it was likely to happen, while a plurality said it would be neither good nor bad. In Turkey, on the other hand, a large plurality said accession would be good thing, but an even larger majority said it was unlikely to happen. Europeans were convinced they would have to accept a new member state, like it or not – and Turkey, to paraphrase Groucho Marx, just wanted into the club that wouldn’t have it as a member.

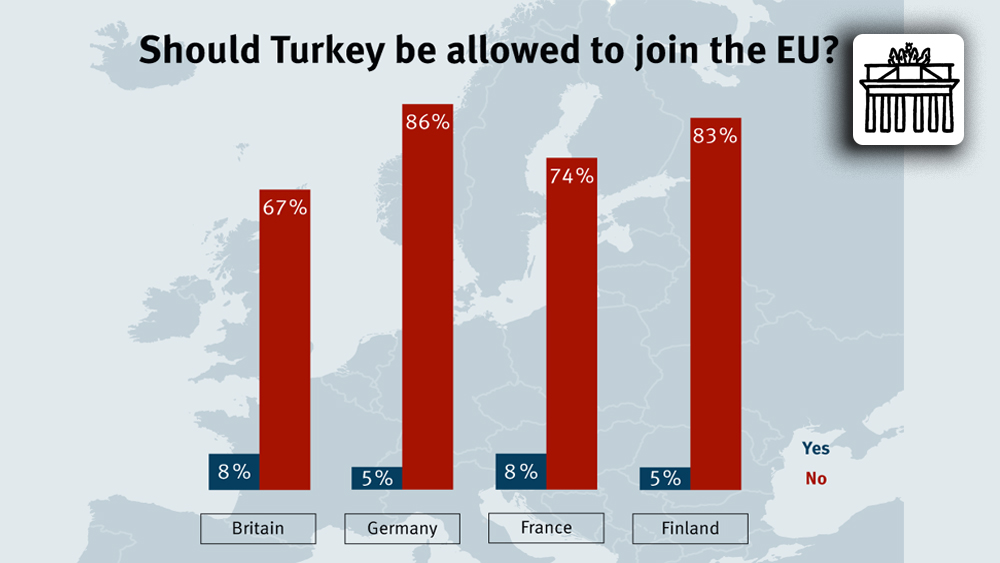

Since then, Europeans’ enthusiasm for Turkish accession has diminished considerably. A poll conducted by YouGov in late July showed overwhelming majorities in every state surveyed, from 67 percent in Britain to 86 percent in Germany, against Turkey joining the EU. Eight percent in Britain and France were in favor of Turkish accession, while in other EU member states the number was even lower.

This may be due in part to simple expansion fatigue – with the eurocrisis still not entirely over, Europeans may want a breather before attempting to absorb another economy into an already fractured and heterogeneous common market. To a certain extend the poll data bears this out: in Britain, 67 percent said Turkey should not join the EU, but 61 percent said the same of Israel and 60 percent said the same of Morocco. In France, where 74 percent were against Turkish accession, equal numbers were against Israel and Morocco joining, and two-thirds were against membership for Albania and Kazakhstan. In fact, of all the accession prospects investigated, including Croatia, Serbia, and Ukraine, the only one that enjoyed broad support was Iceland.

Germans, however, seemed particularly hostile to the idea of Turkish EU membership – which may come as a surprise, as Germany is home to the largest community of Turks outside of Turkey itself, with estimates of the total population ranging from 2.5 to 4 million.

That familiarity may be the problem. In an increasingly tense security environment, many Germans are beginning to wonder about the Turkish community’s loyalties, and discussions of the proper response to Islamist terror attacks have, as elsewhere, begun to converge with discussions of immigration and integration. A recently leaked German government report accuses President Erdogan of supporting radical Islamist groups and sees Turkey as a staging ground for extremist groups; and Chancellor Merkel has come under fire for calling on Germans of Turkish origin to “develop a high degree of loyalty” to Germany, a statement other politicians felt was unnecessarily divisive.

According to a July ARD-DeutschlandTREND survey, 90 percent of Germans feel that Turkey is not a trustworthy partner, compared to 72 percent who feel that way about Russia; majorities said they could trust France, Great Britain, and even the United States, chlorinated chicken and the NSA be damned.

If Europe is going to continue working closely with Turkey, work needs to be done to rebuild this trust. Turkish accession to the EU may be a moot point at the moment, but its membership in the European community – small C – remains essential.

Read more in the Berlin Policy Journal App – September/October 2016 issue.