US President Donald Trump does not, to put it lightly, have a warm relationship with Germany, nor with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, against whom he has held a deep but somewhat inexplicable grudge since his emergence on the political scene. Among the topics which he likes to needle the chancellor about – a fictional crime wave this week, the disintegration of the EU the next—there is one to which he always returns: trade.

Trump has endlessly bemoaned Germany’s trade surplus, blaming both an artificially devalued euro and high tariffs for what he sees as a tilted playing field. In March, he tweeted: “The European Union, wonderful countries who treat the US very badly on trade, are complaining about the tariffs on Steel & Aluminum. If they drop their horrific barriers and tariffs on US products going in, we will likewise drop ours. Big Deficit. If not, we Tax Cars etc. FAIR!”

The US president—again, to say it diplomatically—does not devote much attention to the finer points of international trade. There are, in fact, trade asymmetries between the United States and the European Union: The average EU customs duty is 5.2 percent, while the average American customs duty is 3.5 percent; the disparity in customs duties applied to cars is particularly stark, at 10 percent and 2.5 percent, respectively.

There are several sectors, however, where steep duties are levied on the American side as well: The US places a 25 percent tax on small truck imports from the EU, for example. More importantly, because of the degree to which American and European industries are intertwined, implementing retaliatory tariffs—rather than negotiating lower trade barriers in general—is completely self-defeating.

But even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and the US president, despite his best efforts, has made a valid point: most of the EU member states are running significant trade surpluses, and these surpluses are becoming dangerous—for the EU most of all. Since all of the member states are trying to sell their way to solvency and cut domestic spending, there’s no one to buy; and if intra-EU consumption doesn’t grow commensurately with productivity, member states will find themselves dividing up an ever-shrinking cake. At its core, a trade surplus is an excess of national saving over domestic investment. Low domestic investment means slower growth and crumbling infrastructure.

The EU’s aggregate trade surplus of about 3 percent of GDP is not spread evenly across all the member states, but nearly all member states run a surplus: According to the OECD, Germany’s 2016 trade surplus was 8.57 percent of GDP, the Netherlands’ was 8.46 percent, Hungary’s 6.01 percent, Sweden’s 4.25 percent, and Italy’s 2.56 percent. Incidentally, European regulations stipulate that no country’s surplus should surpass 6 percent of GDP. France and the United Kingdom were among the few member states with deficits, at -0.85 percent and -5.78 percent, respectively.

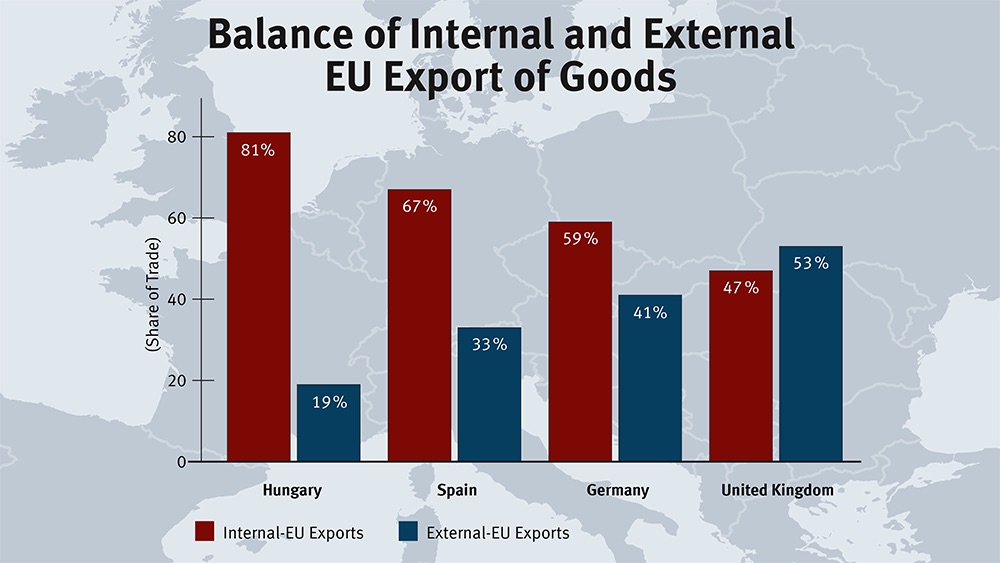

This would be less of a problem for Europe if these countries were trading primarily with external partners. The trouble is that, for the most part, they are not: most EU member states count other member states among their primary trade partners. And as they have all more or less diligently followed the prescribed course of austerity and export-orientation—largely following Germany’s model—the EU has become a shop with 28 salespeople and no customers. By cutting domestic spending, member states are reducing domestic demand for goods other member states might want to sell. And export-led growth has a tendency to merely reinforce existing imbalances in the union: Any eurozone-wide policy to stimulate exports from Greece cannot help but do the same for exports from Germany, preventing the member states with lagging economies from ever catching up.

The countries that have global trade surpluses tend to have surpluses within the EU as well: In 2016, the Netherlands had an intra-EU surplus of €177 billion, Germany €73 billion, Hungary €9 billion, and Italy €10 billion; meanwhile, France had an intra-EU trade deficit of €87 billion, and the UK €115 billion.

Europe’s focus on foreign markets also extends to investment: as the Financial Times reported last year, there’s been a steady drop in investment within the EU since the summer of 2012. Part of this stems from a lack of domestic spending during the various economic crises; but a great deal can also be attributed to the European Central Bank’s decision to maintain near-zero interest rates and the insistence that individual member states reduce their deficits. In an attempt to simultaneously spur growth and balance the books, the EU seems to have plugged some of the leaks in its member states’ coffers, but it’s made itself a less attractive place to invest and reduced the debt instruments with which interested parties might do so.

It should be noted that the Germans themselves have called attention to the problem. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble told the Tagesspiegel last year that he believed the euro was undervalued, saying, “When ECB chief Mario Draghi embarked on the expansive monetary policy, I told him he would drive up Germany’s export surplus.” But Germany also shoulders a great deal of the blame: Citing its “debt brake,” Berlin has resisted running a deficit even when it could have borrowed at near-zero interest rates, choking off one of the potential sources of liquidity—and demand—within the common market.

Trump’s actions will almost certainly do more harm than good, to his own country most of all. But he is not wrong in pointing out that the game is unfair.