“Freedom of movement for workers shall be secured within the Union,” says the Treaty of Lisbon. This is a core pillar of the EU’s single market and a less controversial issue outside of the Brexit debate, where even former prime minister and liberal Remainer Tony Blair has questioned the fairness of letting EU citizens hunt for jobs in the UK without any “emergency brakes” that go beyond the current qualifications.

The details of freedom of movement change from time to time: in April 2018, for example, French president Emmanuel Macron led a push on the EU level to reduce the amount of time that “posted workers” can work in a member-state without abiding by the (usually more stringent) local labor or pension standards. There are also restrictions on when EU migrants can claim welfare benefits. But the principle of allowing EU foreigners in to work is generally accepted, even if some people consider it a necessary evil of the single market. While Europeans do, in the aftermath of the refugee crisis, tend to want fewer immigrants in general and those already here to integrate better, only 29 percent of respondents in the Spring 2018 Eurobarometer poll said they had a “negative feeling” about intra-EU migration.

So much for receiving countries. The debate is somewhat different in the member states whose citizens are trying their luck abroad. That’s because of one buzzword: “brain drain,” or the emigration of skilled or qualified people.

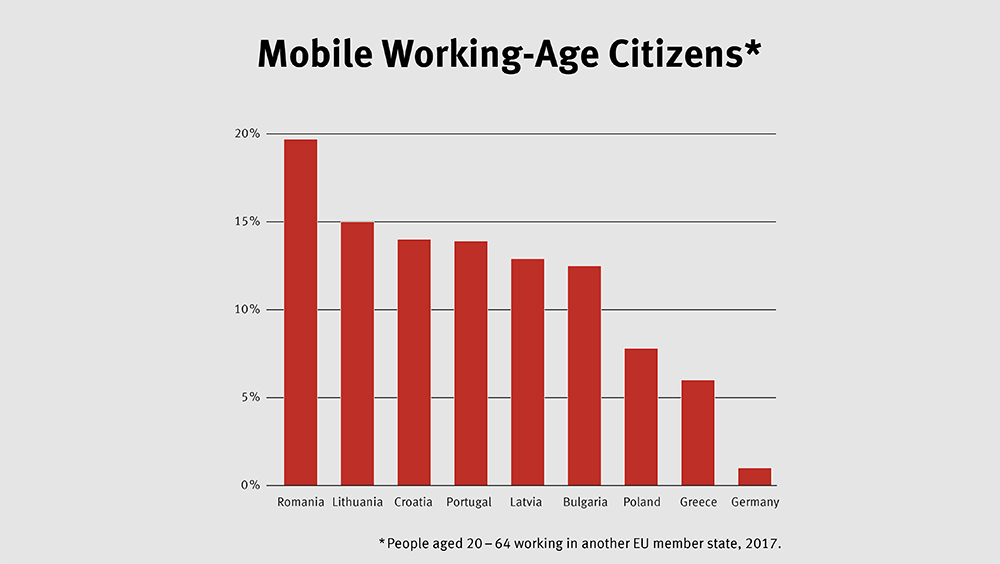

According to the latest figures from Eurostat, in 2017 six EU member states had more than 10 percent of their working-age population working elsewhere in the EU. Romania (19.7 percent), Lithuania (15 percent), Croatia (14 percent), Portugal (13.9 percent), Latvia (12.9 percent), Bulgaria (12.5 percent)—these are mostly eastern member states and less well off than the EU average. While the stereotypes may be of Polish cleaners seeking higher wages abroad, mobile workers in the EU are more likely to have tertiary education than the resident population.

Other statistics help paint the picture of what is happening in central and eastern Europe, where emigration is high, birth rates are low, and pensions are a huge burden on the social welfare state. The Economist points out that tiny Latvia’s working-age population has fallen by a quarter since 2000. Bulgaria’s population, nearly nine million in 1989, had shrunk to 7.1 million by 2017, creating a massive shortage of qualified labor in the country.

Better Than Walls

The “brain drain” issue is seeping into the politics of these sending countries. At a Visegrád summit in 2016, Polish President Andrzej Duda said, “We must stop the wave of emigration … that makes so many talented, creative young people leave our countries.” Poland, like several of its neighbors, has a program to encourage citizens to return and help them with jobs and housing.

One reason that Viktor Orbán’s Hungarian government recently passed a controversial law giving businesses the right to force employees to work up to 400 hours of overtime per year was that nine percent of the working-age population is abroad, and that Orbán has no interest in allowing non-EU migrants to take their places. Audi workers in Hungary successfully demanded an 18 percent raise in February, showing how much bargaining power they have amid a labor shortage. Meanwhile, the Romanian finance minister Eugen Teodorovici has even called for the introduction of a non-renewable, five-year permit for Romanian citizens to work in another EU country.

But there are also real benefits of skilled labor mobility from the perspecive of a sending country. Portugal, for example, was grateful during this decade’s financial crisis that some unemployed Portuguese could try their luck in the stronger economies of Europe’s north until things improved at home. Mobile EU workers may send remittances home, or return later to start businesses, or make personal and business connections that strengthen the bonds between their home country and its European neighbors. For the workers themselves, freedom of movement is a beautiful thing—indeed, minister Teodorovici was quickly forced to walk back what he called an “ill-formulated proposal.”

The fact that a Romanian nurse or Greek data engineer can move to France in search of better wages is literally the point of a free market in a free, integrated Europe, as is the ability of workers in countries prized for their cheap labor to demand better compensation. Economists tell us that labor mobility is a prerequisite for an optimal currency area, as it helps prices and wages adjust in member states bound by the euro. Difficult as things are in the Polish towns whose young and educated have left, today’s situation is vastly preferable to using walls and visa requirements to stop Europeans from living where they want.

Perhaps it’s illustrative to think of EU brain drain in the context of worldwide migration trends. All across the world, people are moving from poorer, rural areas to the metropolises where most wealth is created. Many of the brightest and most ambitious will never return, increasing the inequality between winners and losers and straining social services. This is a challenge not only across borders but also within countries. There are towns in northern England and eastern Germany whose young graduates flock to London and Berlin. However, that mobility only shows up in national-level statistics—and no national governments are proposing restrictions on it.

The correct response, then, is not to restrict freedom of movement within a member state or within the EU, but to continue the redistributive and investment policies that aim to make underdeveloped regions more attractive, whether we’re talking about a small town in Saxony or the capital of Bulgaria.