The tech giants like to present themselves as foreign policy players, acting on an equal footing with nation states. In fact, they are practicing old-fashioned lobbying on an ambitious scale.

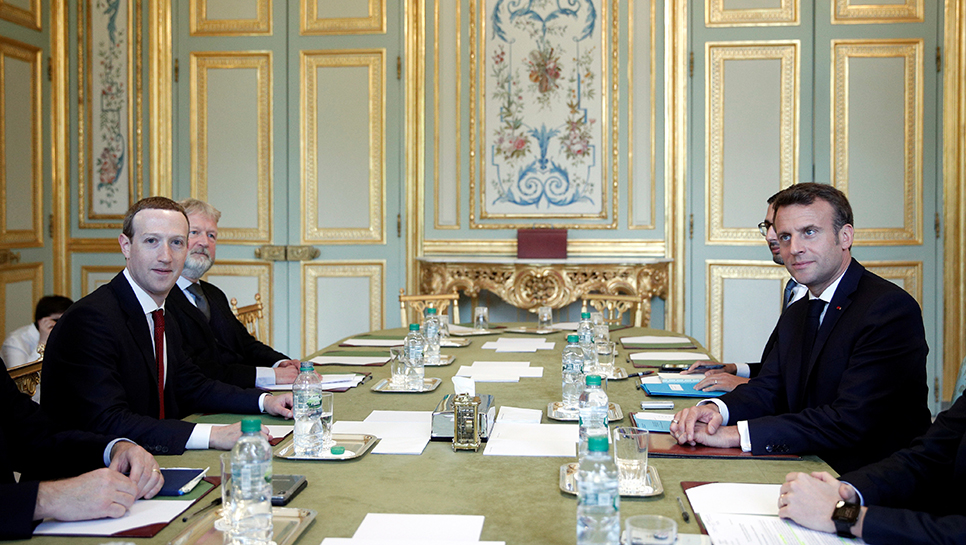

On May 10, 2019, Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg arrived at the Élysée Palace in Paris for a meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron. The images that were released to the press uncannily resembled those from a traditional head-of-state working visit: two men square off across a table in a gilded room, leading their respective teams into negotiation, notepads at the ready, steely and determined looks on their faces.

Today’s tech firms are some of the most valuable corporate entities in history, with revenues higher than many countries’ GDP and user bases larger than the populations of many more. Many of their policy decisions—for example, on the bounds of acceptable public speech online—certainly have significant global ramifications, and squarely lie in the realm of essential human rights, making them significant political actors.

Denmark, having recognized the political influence and impact of the tech sector, appointed a “tech ambassador” to Silicon Valley in August 2017. “Companies such as Google, IBM, Apple and Microsoft are now so large that their economic strength and impact on our everyday lives exceeds that of many of the countries where we have more traditional embassies,” the then Danish foreign minister, Anders Samuelsen, said when announcing the position.

It has become almost a cliché to point out how powerful and “state-like” major technology companies like Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft have become. For some, the Macron-Zuckerberg meeting provides the latest case-in-point: government and firm appearing seemingly as equals, on a level playing field.

But do these companies indeed have “foreign policies” of their own, and if so, what are they trying to achieve? How have tech giants navigated the world’s diplomatic halls? More critically, how might firms like Facebook and Microsoft benefit from being portrayed—and portraying themselves—as diplomatic actors?

Facebook’s Rocky International Record

Mark Zuckerberg has a mixed relationship with European politicians, evading some and embracing others.

For example, a British parliamentary committee investigating “Disinformation and Fake News” tried every trick in the book to get the Facebook CEO to testify in late 2018, including issuing a host of formal summons letters, physically seizing confidential documents from the founder of an American company engaged in a lawsuit against Facebook, and repeatedly highlighting Zuckerberg’s refusal to fill the empty chair via all available channels. In a begrudging hearing in Brussels earlier that year, Zuckerberg managed to set the terms for a remarkably lopsided debate format, fielding questions for 45 minutes and collectively responding for 25—dodging pointed questions, and not providing an opportunity for MEPs to follow up.

Zuckerberg’s April 2019 visit to Berlin included meetings with the Justice and Consumer Protection Minister at the time, Katharina Barley, a member of the center-left Social Democrats, and the co-leader of the Greens, Robert Habeck, who had come out in favour of breaking up Facebook a year earlier. These were markedly less formal than the Macron meet-up. Barley in particular dismissed Zuckerberg’s call for stronger state engagement in a broad range of internet affairs. “Regardless of state regulation, Facebook today already has every possibility to guarantee its users the highest standards of data protection,” she said. Unlike in France, Zuckerberg’s reception in Germany was subdued and not particularly reminiscent of the world of international diplomacy in substance, tone, or optics.

Public-private negotiations clearly lack the protocol and formality of state negotiations. Rather, they depend on the goals the tech firms and states are pursuing, and the images they are trying to project.

Style Not Substance

Among nation states, the principle of sovereign equality applies. When it comes to negotiating with tech firms, however, states ultimately still have the upper hand—whether the setting is formal or informal.

Much of this is due to the tenuous legal standing of digital platforms for user-generated content. Internet companies have long faced a conundrum, summarized by digital media scholar Tarleton Gillespie in his recent book Custodians of the Internet: to avoid offending users and advertisers, firms have needed to develop systems for policing and removing objectionable or illegal material. But by doing so, they appear to take on responsibilities for that content as its publishers. This leaves them exposed to lawsuits and legal sanctions that can threaten their commercial viability.

The answer, enshrined in early internet law in the United States and the European Union, was a principle called “intermediary liability,” intended to grant some protection to companies that made those kinds of “moderation” decisions. Without this limited immunity of sorts, platforms could be found legally responsible for every copyright infringing video they hosted, every piece of libel or defamation that was published on someone’s profile page, and every instance of illegal content accessible in a country (such as Nazi material in Germany).

Lobbyists With Deep Pockets

The majority of international “foreign policy” activities by the advertising-dependent platforms are about avoiding the costly repudiation of these legal frameworks. They have been savvy in terms of their use of political voice, engaging in massive international lobbying efforts, shaping legislation, and crucially, rallying support amongst civil society and advocacy groups to prevent major legislative changes.

According to the Corporate Europe Observatory’s LobbyFacts project, Google spends more on EU lobbying than any other individual company (over €6 million in 2017 alone) and even many industry associations. Microsoft is not far behind, having spent around €4.5 million a year on Brussels lobbying in the past decade, topping firms such as Shell, ExxonMobil, and Bayer. And while it remains a controversial subject, growing attention is now being paid to the way that large amounts of funding from platform companies may affect the willingness of civil society groups (especially American ones with ties to Silicon Valley) to advocate for or against certain forms of regulation.

One might look at the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism (GIFCT)—a coalition of firms that have committed to combating the spread of terrorist material—where tech executives, academics, and the Western national security establishment rub shoulders. They give the impression of attending a high-flying forum for international diplomacy. But GIFCT was created at the behest of the European Commission, which coerced the firms into a set of commitments through its Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online. Despite its trappings as an international organization, it is effectively about pacifying regulators.

Microsoft: An Image of Neutrality

The biggest American tech firms are not merely reactive; they also attempt to proactively set the agenda themselves.

In early November 2018, for example, Microsoft President Brad Smith swept into the main chamber of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague’s iconic Peace Palace to deliver an address on contemporary peace and conflict. He presented a video—“Cybersecurity and the World: A Time to Reflect, a Time to Act”—which featured himself and Microsoft’s communications director, Carol Ann Browne, walking the battlefields of Verdun and discussing the perils of war and arms races with the head of the French war graves authority. The message eventually pivoted to the May 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack that hit the British National Health Service and other businesses around the world, apparently in order to demonstrate the impending threat of World War I-like catastrophic digital conflict.

Microsoft has been uniquely proactive in pitching itself as a particularly security-aware and responsible international technology company. As a creator of consumer software and hardware as well as a provider of enterprise IT services, Microsoft is less worried about intermediary liability regulation. Instead, it has sought to increase its international profile and legitimacy within contemporary cybersecurity policy debates.

In a related 2017 speech, Smith called for a “Digital Geneva Convention” to limit the use of offensive cyber operations by states, and has since spearheaded a complex lobbying effort focused at various private and public stakeholders in the internet and cybersecurity governance ecosystem. These varied efforts have been unified by their use of loaded internationalist imagery and concepts—such as the ICJ’s halls, the Geneva Conventions, the Red Cross, and the battlefields of Verdun—to grab hold of the lineage of international peacebuilding efforts and emphasize Microsoft’s role as a legitimate, savvy, and important player and measured mediator in international politics.

Cybersecurity Statesman

Smith frequently appears at international events with foreign ministers and other high-ranking officials, which in effect grants him authority as a cybersecurity statesman of sorts. He has been an effective operator thus far, playing a leading role in crafting the declaratory “Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace,” announced at the 2018 Internet Governance Forum alongside the World War I Armistice commemoration. The call brings together a large group of states, civil society organizations, and firms in a commitment to increase digital security: “States must work together, but also collaborate with private-sector partners,” the agreement reads.

Alongside this effective instance of agenda-setting, it is worth pointing out that Microsoft’s own recent past of public-private interaction includes being the NSA’s very first partner in the infamous PRISM surveillance program disclosed by Edward Snowden. In recent months, the company has faced criticism and internal controversy due to new contracts with US Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Department of Defense. Smith’s presentations also conveniently avoid any specific responsibility Microsoft may have had in the incidents he discusses, including WannaCry (which involved a vulnerability in Windows systems).

A charitable interpretation might suggest that the imagery of international diplomacy is both substantively appropriate considering the gravity of the issues at stake, as well as stylistically helpful in describing the situation at hand. A more critical perspective, however, might suggest that Microsoft and its shareholders clearly benefit from the association, and the company is itself actively pushing this framing.

Partners in Governance?

While Amazon and Twitter have kept a low profile, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft appear to increasingly be seeking a greater public role in governance. They are attempting to move away from the coercive, hierarchical relationship that was evident in processes like the EU Internet Forum and resulted in the hate speech code of conduct.

Macron drew Zuckerberg to Paris by threatening new legislation, but also dangled a carrot to match his stick. He proposed a “co-regulation” approach to content governance that offered Facebook a seat at the negotiating table, providing the company with a potential opportunity to shape policy outcomes to better suit their own preferences.

This initiative and Microsoft’s role in the Paris Call demonstrate how Big Tech has been exploring ways through which it can de-politicize the policymaking process, making it less confrontational and more akin to equals or colleagues steering outcomes towards a set of common goals—be it “protecting the accessibility and integrity of the Internet” (in the case of the Paris Call) or “combating the dissemination of content that incites hatred” (in the French example).

While other governments seem to be less enthusiastic than France about granting tech firms co-equal partnership, momentum appears to be building across Europe. A recent Council of Europe initiative announced with Apple, Facebook, and Google intends to “strengthen its cooperation with the private sector in order to promote an open and safe internet,” creating a framework through which companies can “sit side-by-side with governments when shaping internet policy.”

Even though such initiatives may be non-binding, they carry weight by ceding some responsibility from elected officials to company representatives. Both politicians and the public should be mindful of portraying tech firms and states as equal partners, and transferring diplomatic metaphors to the public-private realm. This imagery may be more helpful to Big Tech’s public relations efforts than to crafting sound public policy.