Chinese engineers and workers on Belt and Road Initiative projects often spend many months away from their families. In Kyrgyzstan, however, some see a silver lining.

“What do I get in return for this sacrifice?”, Wu says, echoing my question.

He’s chewing over those words, thinking about the last four years he’s spent apart from his family. Wu married his wife in 2015, and he left that same year, moving to work for China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) in Kyrgyzstan. He spends three months over winter back in Hubei province, but those remaining nine months a year aren’t easy—his daughter, now two, was born to him while he was working over 5000 kilometers from home.

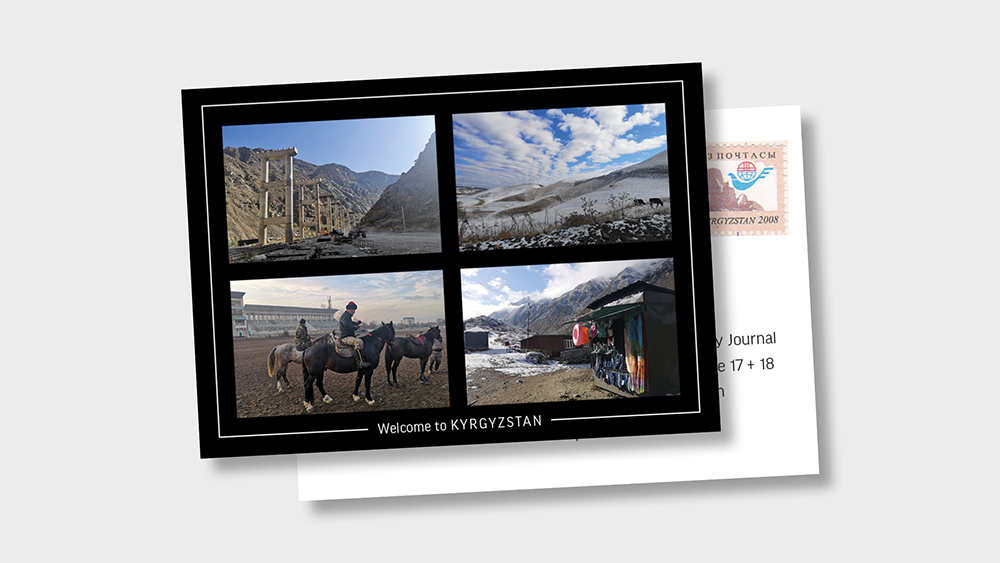

“That’s a very good question—I also ask myself this often,” Wu says, suddenly serious. I’m being shown around the construction site of an important project that will soon provide an alternate route between North and South Kyrgyzstan. At the moment, there’s only one road connecting the capital, Bishkek, to the south of the country, and in winter it can be closed for days.

Snowcapped mountains are painted against the sky on all sides, like a movie scene backdrop. The work camp is basic, pared back, but also a trove of sophisticated road building wizardry. In simple container box laboratories, asphalt cores are tested for maximum density and concrete blocks are cured in baths of water.

All but one of the Kyrgyz employees I speak to highlight the impressive work ethic of the Chinese, as well as the cultural gulf that lies between Kyrgyz and Chinese workers. “They came here to work hard and make money,” one tells me, “you’ve seen the huge projects—they need to work hard, only with their methods can they finish, can they do something so impossible.”

The Chinese workers sing a different tune. They may work non-stop in challenging conditions, but they have an easier time of it than they would at home. “The pressure in China is really great, I like the pace of life here, it’s much slower and easier,” one tells me. Central Asia is an underdeveloped space that can help absorb Chinese overcapacity, but it also provides an opportunity for escape on an individual level.

Working abroad also provides opportunities for ambitious young engineers. Wu repeats my question a second time: “What do I get…” Then he says more decisively, “There are three aspects to it: one, this project is big, and so I can increase my professional knowledge; two, I widen my personal field of vision living in a foreign country; three, just life needs—the benefits are good here.”

And with those words, his sadness sinks back below the surface, and the moment of vulnerability has passed.