When “polite people” do impolite things, they can redraw the map of Europe. After facilitating the annexation of Crimea, Russia’s “gentlemen soldiers” have become a national meme.

The irregular Russian soldiers who took Crimea from Ukraine were so pleasant to civilians they became known as the vezhlivye lyudi – the polite people. Their pleasant attitude worked: they redrew a crucial border while barely firing a shot. In some circles, they have even attained pop star status – you can buy branded cups and T-shirts at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport.They appeared late in February 2014, hundreds of heavily armed and well-equipped Russian speakers who suddenly popped up in Crimea. They wore no insignia, nothing to say who they were. And they seemed to have no commander – apart from common decency.

They were all extremely polite to locals, and hardly ever drew their fancy weapons. Their method of taking over Ukrainian military installations was not to storm in; instead, they kindly advised the soldiers to stay inside, and blocked their way out. There were only two “incidents” in which two Ukrainian officers were killed and another wounded.

President Vladimir Putin denied these polite people existed for more than a year. But other Russians had little doubt that the gentlemen soldiers who were busy being so polite in Crimea were their guys. NATO was equally convinced, although less impressed by their good manners. Later Putin admitted that, yes, the well-behaved soldiers were his.

Russian journalists and bloggers were already miles ahead. Boris Rozhin, who blogs as Colonel Cassad on LifeJournal, coined the term “polite people” back in February 2014. The name fit the soldiers’ role in the new hybrid war scenario, sprinkled with a touch of blogger irony.

Either Voentorg JSC missed this irony or doubled down on it. The firm, a leading supplier of nonlethal ammunition to the Russian armed forces, adopted the name “polite people” – even adding a photo of a soldier with a cat to create an all-Russia trademark.

The polite people are a sign of the continuing militarization of Russia’s foreign policy, and the Kremlin’s lack of respect for rules and norms. Political writers are increasingly – politely – accepting the idea that a hybrid war can be waged anywhere without formal announcement. If the troops say “please” and “thank you,” what’s the problem?

The other thing that the polite people demonstrate is how far the Russian armed forces have evolved over the past couple of decades. In the 1990s and early 2000s, nearly every Russian soldier was a conscript. Yet from 2005, the number of professionals in the armed forces increased from around 30,000 to more than 240,000, and the plan is to push this to half a million by 2022. That would be more than half of all men serving in the Russian uniform – that is, assuming they wear it.

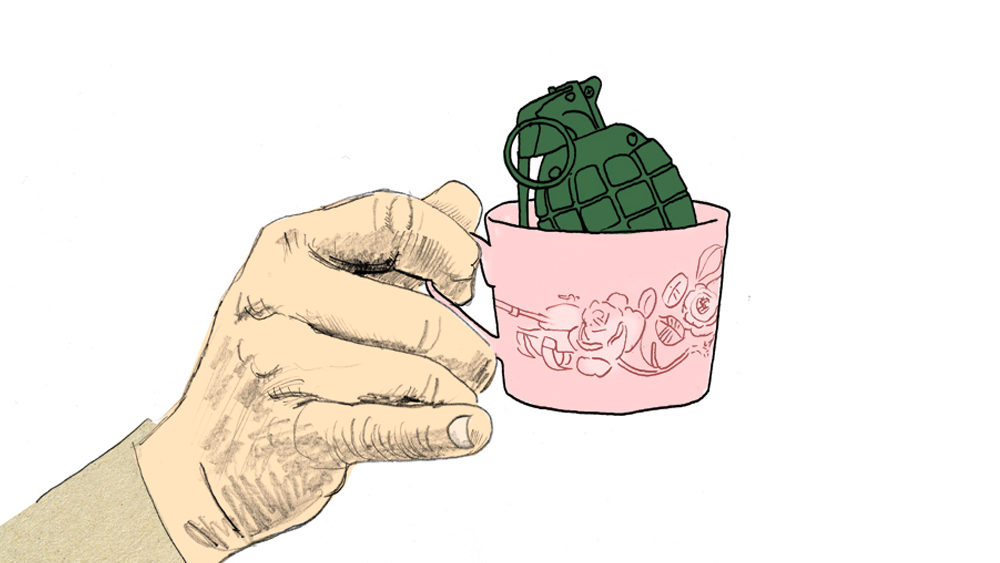

All those sent to Crimea a year ago were contracted servicemen: well equipped, well trained, and psychologi-cally prepared to act even in controversial circumstances. Their politeness may have had less to do with their mothers teaching them manners and more to do with the fact they were far better prepared and armed than the Ukrainian soldiers they faced. In a way, they enacted an updated version of Theodore Roosevelt’s maxim of speaking softly and carrying a big stick.

Could Putin be a polite person? Moscow is as calm as a judo black belt – it can afford to disrespect the rules and ignore the norms of international behavior because it outguns those it faces. And it can avoid a Western military response as long as it remains polite.

Read more articles from the May/June 2015 issue FOR FREE in the Berlin Policy Journal App.