On the night of June 23, European leaders went to bed confident the British referendum would go well. They woke up to a completely new political reality. What’s next for Europe?

The result of the Brexit referendum sent shock waves from London across the globe, but also thrust the European continent into the spotlight. It wasn’t just the future of the United Kingdom hanging in the balance, but that of Europe as a whole. The EU’s second largest economy – a military and diplomatic power with roughly an eighth of the union’s population – had decided to leave. The internal equilibrium of the union was upset, ostensibly in Germany’s favor, and populists from France to the Netherlands were emboldened to call for referenda of their own.

For the EU, the British exit represents an amputation, not a mortal blow – assuming the politicians responsible can rein in the forces Brexit has unleashed. They must resist the temptation to blame UK insularity or the lies of a vile campaign for the outcome and look the unsettling truth in the eye. The referendum result directly contradicts the Brussels doctrine, the ancient adage of European politics that dates back to the coal and steel days of Robert Schuman and Konrad Adenauer: Mutual economic interests will cement ties between grateful European peoples. British voters turned this axiom on its head. Their aversion to immigration was stronger than their fear of the economic consequences of leaving. Identity politics trumped economic interests. The tidal wave they unleashed has also upended the commonly held belief in Brussels that integration is a one-way street. Indeed, even more countries might wish to leave the union, and ceding EU powers back to the national level is no longer unthinkable. Simply put, Europe has until now marched confidently toward an ever closer union. The certainty of that course has now shown itself to be an illusion. Europe feels its historic fragility. Turning this into a strength will mean embracing public debate and accepting that controversy and conflict are the stuff politics is made of – not a threat but rather a sign of life.

In the aftermath of the British referendum, three fundamental questions have come to the surface: How can Europe create a relationship with its people? Is the union even equipped to react to major upheavals? Who leads in times of uncertainty? Put more starkly: how to deal with European voters, Brussels regulations, and German dominance?

Angry Rumblings

On the first question: It isn’t just British voters who are unhappy. Angry rumblings are growing louder across France, the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark as well. Trust in EU institutions is at an all-time low. The eurocrisis left deep scars, both in countries forced to implement austerity measures and in those that had to pitch in with their own taxpayer money. The union lost credibility once again on the refugee crisis – first, by ordering reluctant member states to take in asylum seekers, then by attempting to stem the flow of people with a controversial deal with Turkey.

The EU is stuck with a fundamental dilemma: Its mission is primarily concerned with expanding the freedoms and opportunities of its citizens, and less so their protection. The union has been dismantling borders since it was established. It champions the freedom of movement to study or sell goods across borders, to travel or work. It makes Europe – in the words of Michel de Certeau – a space and not a place. It has equipped the well-educated, the young, and entrepreneurial with mobility.

But it has also disrupted a broad and underserved part of the population along the way. For them, the EU is one more piece of a rapidly globalizing world that moves in endless streams of goods and people, and they feel they are powerless to fight back – the sentiment that swung the British vote to “leave.” As long as there is no better balance between the freedoms the union creates and the protections it provides, voters elsewhere will continue to look to their own state for shielding them from Europe, too.

Disillusionment with centrist politics has also given way to political extremism on the fringes. In many member states, a well-organized nationalist sentiment has turned against the EU in the name of sovereignty and identity. This centrifugal force has stepped up pressure on Germany, the traditional “power in the middle” (Herfried Münkler), to hold the European center together. Of course, a glance at the US elections and the rise of Donald Trump shows Europe is not alone in facing populist nationalism. And yet it has a specific problem. For many voters, Brussels has transformed into a sort of foreign occupying power.

That lies in stark contrast to national politics. Every day a national government – take the one in Poland, for example – makes decisions that can be contested by opposition parties and even trigger protests or strikes. As a general rule, however, even the fiercest demonstrators accept the legitimacy of the Polish government itself. They may call on the Polish prime minister to step down tomorrow, but they would still consider him “our (infuriating) prime minister” or speak of “our (bad) laws.” This “our” is Europe’s Achilles’ heel. Few people consider European decisions “our” choices, or European politicians “our” representatives. This feeling of ownership – incredibly difficult to grasp, let alone to create – is essential to conferring legitimacy on joint decisions.

If the aim is to forge a real bond with citizens, an indispensable first step is to acknowledge that the European game is not taking place primarily on Brussels’ turf. European politics are played out between the governments, parliaments, judiciaries, and citizens of all the member states. Europe cannot be reduced to a few acres of office space in Brussels. Europe can only be built with its people, not without.

Reacting to Surprises

The second fundamental question the Brexit vote raises is this: Is Europe, hemmed in by Brussels’ rules and regulations, in a position to react to surprises? Here, a fascinating metamorphosis has taken place in recent years. After spending decades working to construct a common market and a developing a system of regulatory politics, member states have been forced to take on a new role since the financial and geopolitical drama of 2008: they are now also practicing a “politics of events.” They have saved a currency, engaged Russia in a battle of wills, taken on hundreds of thousands of refugees and now, they must wrestle with the demons of Brexit. This transformation started with the fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification, when the Maastricht Treaty built a new “union” alongside the old “community;” the structures created then are being put to the test now.

The politics of events is qualitatively different from the regulatory politics that dominated Europe for much of the postwar period. For member states, it’s no longer only about regulating business and market behavior of other economic actors. Now they also must face the myriad challenges to the common order as a union, and act themselves. Up until this point, individual member states have been tasked with preserving external and internal security. Only member states have armies, diplomats, and security services at their disposal to preserve external and internal security; only they have enough taxpayers’ money to save big banks. This new practice of the union (which Chancellor Angela Merkel briefly called “union method”) has unsettled institutional interests and routines in Brussels (and the locally cherished “community method”). Another unsettling feature: The power asymmetry between EU states – long a taboo subject – is becoming ever more significant, especially when it comes to responsibility for action. Yet there is no practical alternative. In light of the dramatic acceleration of world history since 2008, in light of turmoil in the wider region, developing a common ability to act is a question of Europe’s basic survival, no matter how difficult the path.

The founding idea behind the European Union was to create a system of rules that would both encourage ties between member states and make them more predictable after the “Second Thirty Years’ War” that raged from 1914 to 1945. But when disruptive new events force member states to act together to confront new challenges, the limitations of the original strategy surface quickly. How should they respond when one member state suddenly goes broke, when a neighboring state invades another, when hundreds of thousands of refugees pour across the borders? No project, no treaty can anticipate the capriciousness of history, let alone provide an adequate response.

None of this should come as a surprise. Anyone who regularly reads their country’s newspapers will know that national politics involve a constant stream surprises, setbacks, and scandals, often with utterly unexpected outcomes. In a democratic setting, very little goes to plan. And Europe, a club of volatile democracies, is no exception. Momentum originates from a series of decisions, many of which are made on the national level, where leaders only grudgingly accept that certain problems are better managed together. This political interplay offers a more plausible explanation than either the pseudo-logic of integration theory and federalist teleology or the euroskeptic worldview of evil Brussels conspiracies. Events will continue to offer new surprises, and, against all odds, Europe is preparing for precisely that.

One indication is the influence that heads of state and government wield in the European Council. This forum was set up in 1974 as a counterweight to the Brussels rule factory, and it has stood at the forefront of the politics of events since 1993. The circle of presidents, prime ministers, and chancellors takes up the task of conquering the storms that beset Europe; in the eurocrisis, for example, the central institutions of the union had neither the financial means nor the legitimacy to overhaul the rules that lay at the foundation of their very existence. Between 2010 and 2012, Chancellor Merkel, President Nicolas Sarkozy, and their 25 colleagues drew up the decisions that saved the euro.

Influential European voices like Jacques Delors and Jürgen Habermas sharply criticized the role of those heads of government, decrying a “renationalization of European politics.” But the results can be interpreted instead as an “Europeanization of national politics,” a development that would in fact strengthen the European club as a whole.

Another important aspect of this metamorphosis: while the old, regulatory politics were a matter for experts and interest groups quietly operating under the radar, the new politics of events are squarely in the public spotlight. Europe and its institutions now make headlines; they are the theme of election campaigns and fodder for passionate debate. That adversity is really the other side of the coin: the Europe of markets and trade had to contend with apathy, even mockery, over stipulations regarding the curvature of cucumbers (an indifference political scientists referred to a “permissive consensus”); the Europe of the currency, common borders, and influence abroad summons powerful forces and counter-forces, higher expectations, and deeper mistrust.

The Conundrum of German Power

Brexit has also thrown a harsh light on German power in Europe. The union is not only based on rules and treaties, but also on an internal balance of powers. Yet we are now moving from a union that was dominated by a Paris-Berlin-London triangle to one that is oriented toward Berlin alone. Even before Brexit the equilibrium between Paris and Berlin had been growing increasingly unbalanced, but until recently, Paris could use its political weight to compensate for its economic lag. As the old saying went, France used Europe as a lever to hide its weaknesses while Germany used Europe as a mantle to hide its strength. The eurocrisis signaled a dramatic shift in that dynamic. The German chancellor has become the focus of international attention since 2010; she is the key protagonist in Europe’s drama, even if she is underestimated at home.

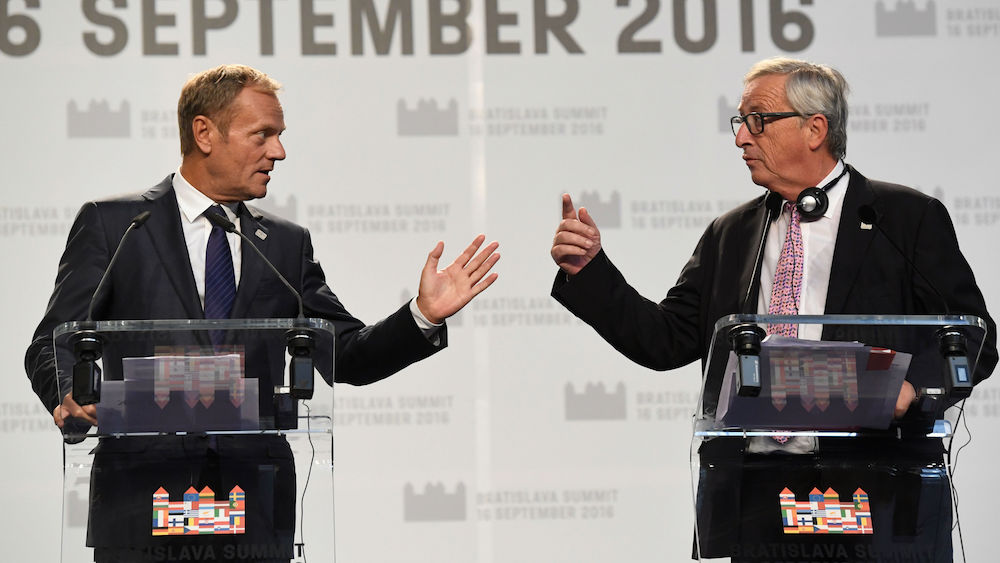

Germany’s power is tangible in the most important political institutions – the European Parliament, the European Council, and the European Commission. The European Parliament has always been a bastion of German power; as the most populous member state, the country has the most parliamentarians (96 out of 751) and controls the Christian Democratic and Social Democratic party groups. The European Council, meanwhile, has long been dominated by France and Germany, in that order. In terms of protocol, a president outranks a chancellor – the French like to ensure that the Germans know their place. But during the eurocrisis, it became evident who really wielded power as Merkel first took the upper role in her duet with Nicolas Sarkozy (“Merkozy”) and then encountered dwindling resistance from a hesitant François Hollande. Finally, the commission took a decisive turn in 2014, when Juncker took office as president. Commissioners used to have a French, a British, and a German adviser to maintain connections to all three major capitals; now, with 31 Germans (among whom are five chefs de cabinet), 21 French, and 18 British, there was a clear tilt toward Berlin.

Germany’s moment has come, and that carries significant risks for the country and for the union. Some of these risks have been acknowledged; others have been underestimated.

The burden of German history, for one thing, has been acknowledged. Even seventy years after Hitler, foreign caricaturists and political opponents instrumentalize the shadow of Germany’s past. On the other hand, Berlin underestimates how often its European policies are perceived as naked self-interest, even if they weren’t intended to be. The German finance minister in particular fell into this trap during the eurocrisis. “Dr Schäuble” (as his Greek counterpart Yanis Varoufakis always called him) argued from a moral high ground, while the outside world perceived him as a merciless, political power player who wanted to eject the Greeks from the eurozone. The refugee crisis has spurred a similar trend. Germany’s Willkommenskultur, or welcome culture, might have been a noble sentiment, but in Paris and elsewhere it was observed that Germany also has a rapidly aging population and a dwindling birthrate – and thus a use for the well-educated Syrian middle class. That makes the choice no less moral, but it has made the European debate more difficult. It is important that this “hegemonic self-righteousness” (Wolfgang Streeck) is also discussed within Germany.

Nevertheless, German power is not omnipotent. Germany is not a hegemon but rather a semi-hegemon. Even Merkel has often run up against barriers that date back to the times of Bismarck: Germany is too strong to be forced aside but not strong enough to get its way all the time. The Germans are themselves not always aware of this fact. During the eurozone’s darkest days, many Germans had the distinct feeling that they were being left to grapple with the crisis on their own. That was never the case. As the president of the European Council reminded a Berlin audience in 2012: “One quarter from the German purse implies that three quarters come from the purses of other euro countries!”

There is also a further reason why Germany cannot do the work alone, and certainly not without France. German and French attitudes toward certain political concepts are fundamentally different. Their misunderstandings shape European politics. Take the concept of rules as an example. In Germany, rules stand for justice, order, and honesty. In France, they stand for limitation and lack of freedom. In the European context, this has led to mutual mistrust. Paris constantly requests more flexibility, for other countries or for itself (to exceed the debt limit, for example); in Berlin that is perceived as opportunism and a breach of trust. Conversely, the Germans, who see themselves as applying the rules strictly but fairly, often find themselves accused of rigidity, stubbornness, and even of playing power games because they prescribe solutions to the whole without understanding individual needs.

Eventful Times Ahead

Events are the counterpoint to rules, and this is where France excels. In France, an event, even a dramatic one, is a sign of life and renewal; for a French political leader à la Sarkozy, a crisis offers the opportunity to show his or her mettle. In Germany, on the other hand, crises undermine order – they are destabilizing and dangerous. The German public values heads of government who can absorb shocks and still navigate the country through storms, like Chancellor Merkel.

Now the country that prefers to bind itself and its partners with rules will have to take the lead in the new crisis – driving a politics of events. And it will be one of Germany’s most difficult tasks ahead. The paradox is that Paris has worked steadily over the past sixty years to prepare the European club of member states for a role as geopolitical actor, but is no longer in a position to lead now that this decisive historical moment has come. Germany has to provide the necessary leadership – it can “no longer practice a well-tended culture of waiting and seeing” (Münkler), but must be ready to make swift decisions and turn improvisation into an art form. The burden of Germany’s past makes this a tall order indeed.

The year 2017 will be a decisive one. Voters in France, Germany, and the Netherlands will go to the polls, and the results will bear consequences for all of Europe. National politicians in these three key countries will have to convince voters that the EU is strong and capable of acting together. Only then will Europe have a real chance to shape its future.