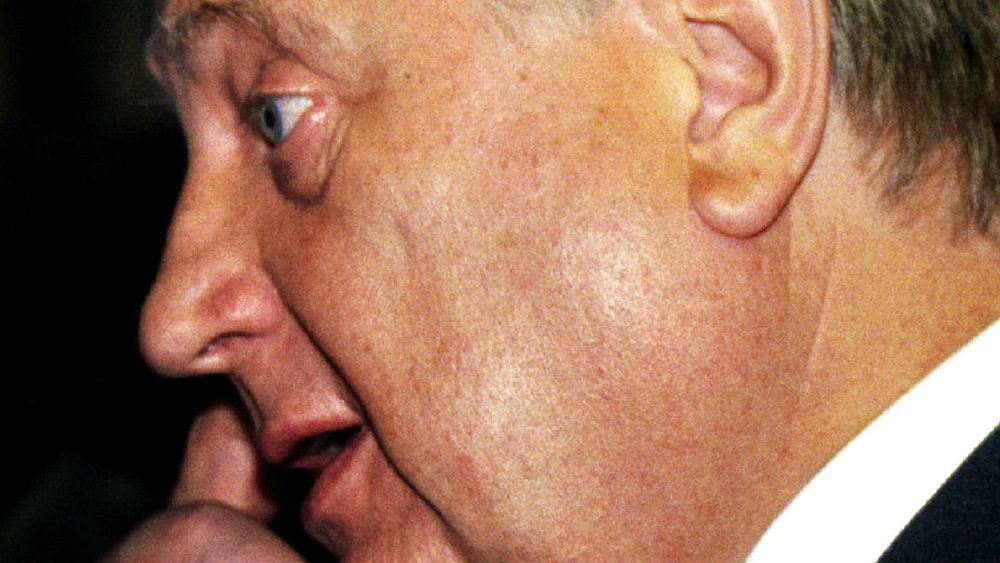

There was nothing he wouldn’t sell and very little he couldn’t buy. Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski was communist East Germany’s foremost capitalist, the creator of a huge empire of shady companies and the facilitator of many a shady deal. Having outlived the state he served by a quarter century, he died on June 21 at the age of 82.

“Big Alex,” as he was called, would have been successful anywhere in the world, such was his cunning, his charm, and his ruthlessness. But it took the Cold War and the peculiar and often murky relationship between the two German states to turn Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski into such a memorable figure.

The son of a former Tsarist officer stranded in Berlin, Schalck-Golodkowski apprenticed as a baker and then a mechanic before taking a position with a state-owned foreign trade company in 1952. He soon switched to the Ministry for Foreign Trade, where he quickly rose through the ranks. At the same time, he completed his studies and earned a PhD in economics.

It was in 1966 that Schalck became responsible for the newly founded department for “Commercial Coordination”, or KoKo. Over the next 23 years, the innocently-named KoKo would earn the German Democratic Republic an estimated 25 billion (West German) Deutschmarks. Among its more respectable deals was the sale of a huge plot of land in central Berlin – today’s premium real estate in Potsdamer Platz – for 36 million Deutschmarks to the city of West Berlin.

Koko also sold antiques and paintings, many of which came from private owners in East Germany who were presented with huge tax bills to force them to sell. Museums were also pressured to give up their treasures. In later years, the GDR even did brisk business in the arms trade.

Through Schalck’s companies – about 200 altogether – West Berlin was able to offload rubble and sewage to East Germany. For hefty fees West German pharmaceutical companies could also test new medicines in the GDR. Companies like Ikea took advantage of East Germany’s prison population for cheap labor.

Even more repugnant was the human trade. From the 1960s onwards, the Bonn government paid a total of about 3.5 billion Deutschmarks to get people out of jail and out of East Germany. More than 33,700 political prisoners were released against hard currency payments. In addition, 250,000 East Germans were allowed to leave the GDR.

Meanwhile, Schalck made himself indispensable by providing imported comforts to the East German elite. For the GDR nobility, KoKo procured Volvos and water faucets, soft porn, exotic fruit, and even the occasional jar of caviar. Ordinary citizens – who had to wait an average of 16 years for a domestically-built car and 25 years for a telephone connection – were bought off with oranges at Christmas.

Unsurprisingly, Schalck had also signed on with the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police. Eventually, he reached the rank of colonel, while also serving as Deputy Minister for Foreign Trade and a member of the Communist Party’s Central Committee.

He became an indispensable interlocutor for West German politicians dealing with the Eastern half of the country. His most famous deal was a huge loan that he negotiated with the Bavarian conservative leader Franz Josef Strauß in 1983. Without this loan, Schalck later claimed, the GDR would have become insolvent by the mid-1980s. This would have been bad timing indeed – in 1985, the Soviet Union would still have been far too powerful to allow a bankrupt East Germany to reunify with the West. In 1989-90, it was a very different game.

Yet that is not how his fellow countrymen saw events. For the longest time, nobody beyond East Berlin’s leadership even knew about KoKo. It was only in the autumn of 1989 that the first reports came out about the elite’s petty privileges and the man who supplied them. The anger was enormous.

In December 1989, Schalck actually fled to West Berlin, making him one of the last – and most surprising – of East Germany’s many political refugees. Mostly for his own protection, he was taken in by police for several weeks before being handed over to the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), West Germany’s foreign intelligence service.

West Germany’s spies questioned Schalck at length about the KoKo empire, but they also protected him and helped him find a new home on the shores of the Tegernsee, a Bavarian lake much favored by millionaires. There has always been speculation that the BND also shielded Schalck from prosecution. While the West German government denied this, Schalck got off rather lightly from the many judicial enquiries undertaken against him.

Was Schalck a loyal servant to his East German state, as he liked to depict himself? Given his international wheeling and dealing, such an image might give him too much credit. Yet it is probably true that there was an element of patriotism to his actions. Schalck deserves a bit more respect than, say, the leaders of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard who control the smuggling into and out of Iran, or traders in blood diamonds.

Until the dissolution of the GDR, Alexander Schalck-Golodkowsk received an annual salary of about 50,000 East German marks, a nice house, and a weekend retreat comfortably outfitted with “his” imported goods. Of course, his life was enviable by GDR standards, but in comparison to the post-Cold War oligarchs, he only earned peanuts.

“Big Alex” was the product of a different time, a figure well hidden from public view who – albeit through questionable means – smoothed relations between East and West. A man neither side will ever tell the whole truth about.