There have been multiple shocks since 2014: Russia’s war against Ukraine, Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, Emmanuel Macron’s bold initiatives. Berlin’s only answer is to play dead.

Helmut Kohl once described Germany as “only surrounded by friends.” The re-unified country, had “found its international place,” the former chancellor reckoned, “without breaks (…) with the foreign policy tradition of the old Federal Republic.” That is very hard to argue today. Rather, Germany is seeking its place again. The international order is crisscrossed by fault lines, and the foreign policy tradition of the Federal Republic must prove itself in an environment full of old-new great power rivalries.

Ambivalence permeates almost all foreign policy relationships. US President Donald Trump, of course, comes to mind first. But he is only the most flagrant case. German diplomacy moves in a world full of two-faced frenemies, as a cursory glance at (some of) the most important opponents shows.

Janus-Heads Everywhere

China is Germany’s most important future market, but its technology-driven authoritarianism also poses the greatest threat to freedom worldwide. The United States is urging Germany to decouple itself from the People’s Republic: this is the background to the dispute over Huawei. “Decoupling” is out of the question for Germany because of the density of economic interdependence, but the protests in Hong Kong and the revelations about the Gulag system in Xinjiang make it seem advisable to reduce economic and political dependence on Beijing wherever possible—especially with such a crucial infrastructure as 5G.

India offers itself as an alternative, democratically governed growth market, but under Prime Minister Narendra Modi it is also drifting dangerously toward authoritarian nationalism, with repressive, Islamophobic domestic politics and an aggressive, revisionist foreign policy—as recently demonstrated by the brutal suppression of autonomy in Kashmir.

Thanks to its geopolitical gains in zones of disorder (Syria, Ukraine), Russia is back in the geopolitical game. German policy on Russia, however, flitters helplessly between pipeline construction and sanctions. Moscow will gain even more influence over Germany’s energy supply through the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, while Putin is arming his country more and more aggressively against Germany’s eastern neighbors and is quite openly positioning himself as a champion of an illiberal global movement. The new pipeline also weakens Ukraine’s negotiating position vis-à-vis Russia, which Germany is actually trying to strengthen with sanctions against Russia.

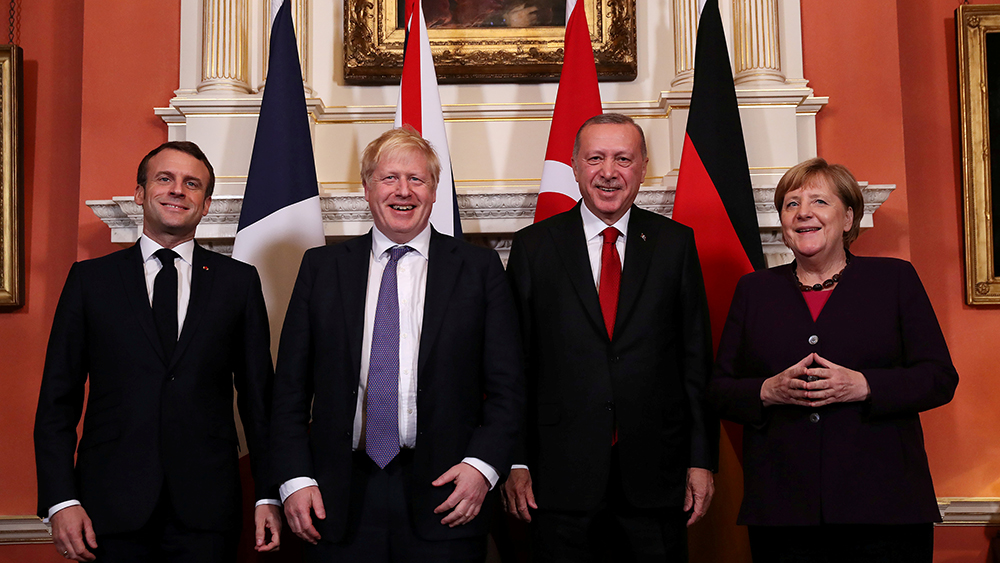

Turkey, Poland, the UK

Since the refugee deal, Turkey has been Europe’s de facto border guard, caring for millions of Syrian refugees and keeping them comfortably far away from the Europeans. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan believes, of course, that he can blackmail the EU with these refugees, whom he keeps threatening to “send”—just as he puts NATO under pressure with his overtures to Putin. His intervention in northern Syria, which violated international law, triggered a debate about Turkish NATO membership and has led to a far-reaching ban on arms exports to a country that is still a NATO ally.

Poland—twice as important for German foreign trade as Russia—has been courted by Berlin for years, and yet the PiS government regularly threatens to demand reparations for German crimes during World War II. Warsaw is pushing ahead with its efforts to dismantle the separation of powers and is subordinating Holocaust remembrance to an all-dominant national narrative of victimhood in a troubling way (which Germany criticizes only cautiously for fear of further fueling demands for reparations).

The United Kingdom is leaving the EU, reducing its geopolitical heft and indirectly exacerbating the problem of burden sharing within Europe because Britain has always made an above-average contribution to collective defense (spending constantly more than 2 percent of GDP for defense). If in the future more than 80 percent of NATO spending comes from non-EU countries, Germany in particular will be singled out for its shortcomings. Keeping the breakaway UK as a partner after Brexit will be one of the most difficult tasks in the coming years.

The Cost of Moral Clarity

The list could go on. As different as these cases are: politics in a world full of frenemies demands a high tolerance for ambiguity. It must do without grand gestures and pseudo-radical proposals that suggest “moral clarity” but often achieve the opposite of what is desired.

Unfortunately, there are plenty of them in the German debate, such as the idea that cutting Poland’s EU agricultural subsidies because of the PiS government’s controversial justice system reforms would somehow bring PiS back on the path to the rule of law. Similarly, pushing Turkey out of NATO (fortunately almost impossible according to the statutes) would be against the interests of Germany and the alliance. Erdogan would simply tie himself to Putin even more closely.

And capping defense spending on the grounds that more should not be given because “a racist sits in the White House” (SPD parliamentary group leader in the Bundestag, Rolf Mützenich) would confirm Trump’s prejudice that the US is exploited by its unappreciative NATO partners, who despise their protector. Equally short-sighted are the widespread fantasies of punishing the renegade British―some Germans would love to see them feel the negative effects of their exit from the EU club.

Such proposals serve more to set moral boundaries than to achieve a strategic goal. As Jan Techau of the German Marshall Fund has argued, the overriding need for self-affirmation in the German foreign policy debate leads to a paralyzing uncertainty of action: “Moral insecurity leads to a compensatory, self-centered moralism, which in turn produces the feeling of moral superiority.” But this psychological need is not the only explanation for the German foreign policy paralysis.

Three Shocks

Three shock-like experiences have provoked confessions by leading German politicians that they want to assume “more responsibility:” the Ukraine crisis (2014), the double blow of the Brexit referendum and the Trump election (2016), and finally the alienation between Paris and Berlin (2019). The sacred vows that Germany would become more involved had barely been made before they were overtaken by the next crisis.

The first shock was seeing how Putin’s Russia has gone from being an unwilling partner to an open opponent and has forcibly redrawn borders within Europe. The US and the UK, the two founding nations of the Atlantic system, the two nations that first reeducated Germany as a model pupil of the liberal world order, are taking a nationalistic turn. They see the EU—the decisive medium for Germany’s political and economic resurgence—as “a foe” (Trump).

And now France, Germany’s most important remaining partner in Europe, is going its own way. French President Emmanuel Macron single-handedly blocked the accession process for the Western Balkans and launched a new Ostpolitik with Vladimir Putin, also without discussion. He also declared NATO to be “brain dead,” thus confronting Berlin with the impossible choice between an Atlantic alliance or European defense. An ancient dilemma from the 1950s has returned: Germany is supposed to decide between Washington and Paris.

Catch-22 of German Security Policy

This calls into question Germany’s preference for not taking sides but rather striving for European cohesion and the expansion of NATO at the same time. This has been a constant of German foreign policy since the failure of the European Defense Community in 1954 and Germany’s subsequent accession to NATO.

For a long time, it seemed not only that the two weren’t mutually exclusive, but that they were almost conditional on each other: NATO was the security policy framework that made European unification possible. Trump and Macron are now questioning this, and their attacks complement each other in this respect. Trump (like his predecessor Barack Obama) no longer accepts that the US should forever be Europe’s guarantor of security, while the Europeans (in his eyes) are fleecing the US economically and at the same time building new gas pipelines to Russia. Macron, on the other hand, has concluded from Trump’s unpredictability that it is an imperative of European sovereignty to build an alternative to NATO as soon as possible.

This results in a kind of catch-22 of German security policy: if Germany were to reach out to Macron over his project, Trump would have another reason to question the alliance. And the Eastern Europeans do not trust Germany and France to defend them against Russia. So they would try to bind themselves even more closely, bilaterally, to the US. In terms of defense policy, Europe would be divided into different zones of (in)security—the opposite of the desired European sovereignty.

The Fragile Munich Consensus

Although key German interests are at stake here, Berlin is purely reactive in this debate. While Trump, Macron, Putin, and Erdogan drive the action, the German government largely limits itself to reviewing the initiatives of others.

Why? It was only six years ago that the “Munich Consensus” was reached at the Security Conference in January 2014—when Germany’s federal president (Joachim Gauck), foreign minister (Frank-Walter Steinmeier) and defense minister (Ursula von der Leyen) made almost identical speeches that all saw Germany taking “greater responsibility” in the world. They encouraged the country to face these challenges self-confidently. Gauck conjured up a “good Germany,” an adult, widely respected country. It had something to give back to the world, he said; Germany had to change from a consumer of order to a producer of order.

Shortly after those Munich speeches, Putin began a hybrid attack on eastern Ukraine, occupying the Crimea with “Green Men” without badges. The Russian leader to whom only six years earlier Steinmeier had offered a “modernization partnership” was waging war to move borders in Europe.

The world of “new responsibility” was not supposed to be this rough. When Berlin foreign policy-makers are asked when the latest uncertainty about Germany’s role in the world began, they mention the Crimean invasion more often than any other event.

Wooing Berlin, Disrupting Europe

According to the Munich Consensus, Germans had to do more to maintain the existing order. But the notion that this world order could be questioned not only by its opponents, but from within—by its previous guarantor, the US—was beyond the power of foreign policy imagination at the time.

That’s why the Brexit decision and Trump’s choice were so shocking. Angela Merkel’s lapidary remark in a Trudering beer tent in May 2017 summed up the new situation in a nutshell: “The times when we could rely on others completely are to some extent over.” The situation didn’t seem hopeless at the time, however: a few weeks before Merkel’s campaign speech, Emmanuel Macron had defeated Marine Le Pen. That September, Macron gave his great Sorbonne speech, in which he set out the program for a sovereign “Europe that protects.” He had deliberately scheduled the speech with Germany in mind, right after the Bundestag elections.

After Chancellor Angela Merkel’s failure to build a coalition with the Liberals and the Greens, her third “grand coalition” with Germany’s Social Democrats started in March 2018 on the basis of a coalition agreement including a passionate chapter on Europe that called for a “breakthrough.” But little action followed these noble words. Macron did not receive a concrete response from Berlin to his numerous proposals. How could it have done so? The coalition was always divided on crucial issues such as European defense, migration, or the European budget and was therefore unable to speak or act.

The deafening German silence on Macron’s European sovereignty initiative leads directly into the recent crisis. After his enthusiastic proposals for reform were rebuffed, the French president switched over to disruption and questioned the EU accession process for Northern Macedonia and Albania, EU Russia policy, and finally NATO.

Now, he is getting his reaction: German politicians haven’t for many years talked about NATO as enthusiastically for many years as they did after that “brain death” remark. Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer tried in several speeches to revive the Munich Consensus: Germany must do more for common defense, she said, not just as a partner but with its own initiatives, perhaps even northern Syria, Africa, or East Asia. After some hesitation, both the chancellor and Foreign Minister Heiko Maas also made a passionate case for NATO as Germany’s only reliable life insurance. The 2-percent promise would certainly be fulfilled—around 2030.

Twilight Period

It would be very bold to make forecasts about this crucial year of 2020. But one thing can be said: domestic and foreign political instability are a dangerous combination.

A foreign diplomat who has been observing Germany for decades (and prefers to remain anonymous) explains the “paralyzing ambiguity” of German foreign policy as the effect of a “twilight period.” Germany is in a double transition: Angela Merkel apparently cannot and does not want to provide any more impulses. And while Germany is waiting for a change of power at home, foreign policy is also in transition, during which the American-centered order is crumbling without a new one being foreseeable yet. Germany is fleeing the double stress of domestic and foreign insecurity and in a way is playing dead.

The unspoken question is: what if Donald Trump wins a second term as President of the United States in November 2020? That is the question that hangs over all strategic considerations—not only in Germany. Uncertainty about the outcome of the impeachment process and the presidential election influences calculations in Beijing, Moscow, Paris, London, Brussels, and Berlin.

American elections are usually not decided by foreign policy. However, this election will undoubtedly be decisive for the foreign policy orientation of the US. It will determine whether the world has to prepare for another four years of disruption in the name of America First—an America that knows only opponents or vassals—or whether a (at least partial) return of the US cooperating with its allies again seems conceivable.

Expect More Shocks

And yet it would be wrong to fixate on this question. It is risky to bet on Trump’s exit. Not only because his re-election doesn’t seem unthinkable. Even without this president, there would be no return to a status quo ante.

NATO would breathe a sigh of relief if Trump lost, but the pressure for more burden sharing would remain, and the doubts about the commitment to collective defense would by no means disappear. They would perhaps even grow under an explicitly left-wing US president. A Democratic successor to Trump would perhaps choose less aggressive means against China. But the perception of Beijing as a systemic rival is a consensus position in America.

A more confrontational tone could even find its way into Russia’s policy if insights from the Mueller Report and the impeachment hearings become the basis of policy: a Democratic president would have a score to settle with the election manipulator Putin while the Republicans would boost their profiles by continuing to act as Russia apologists, in a blatant reversal of their previous role.

The questions that have thrust themselves on German foreign policy under Trump’s presidency would remain, even if he had to move out of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. How can we succeed in building a European defense without further damaging NATO? Can Europe agree on a Russia policy with gestures of détente coming from Paris and new-old fears rising in Warsaw? How should Germany behave in the new Cold War between the US and China?

There is no end in sight to the turbulence, not for domestic or foreign policy. The three shocks of recent years will not be the last. One thing is clear: German (and European) foreign policy can no longer be geared to who sits in the White House. This is a helpful insight for which we should be grateful to Donald Trump.