The digital age has given rise to new threats against liberal democracies―threats that are independent of geography and asymmetric by nature. To face them, we need a “Cyber NATO.”

The digital era, with all of its benefits, has profoundly changed the security environment of liberal democracies. We face potential destruction of national infrastructures and militaries in ways unimaginable a quarter century ago. Even the electoral process in a number of democracies has come under severe threat, with attempts to alter outcomes in a number of elections in the past two years. The response should be a new “Cyber NATO,” a coalition of liberal democracies that better meets the ubiquity of threats. This will be difficult to achieve, yet the alternatives are worse.

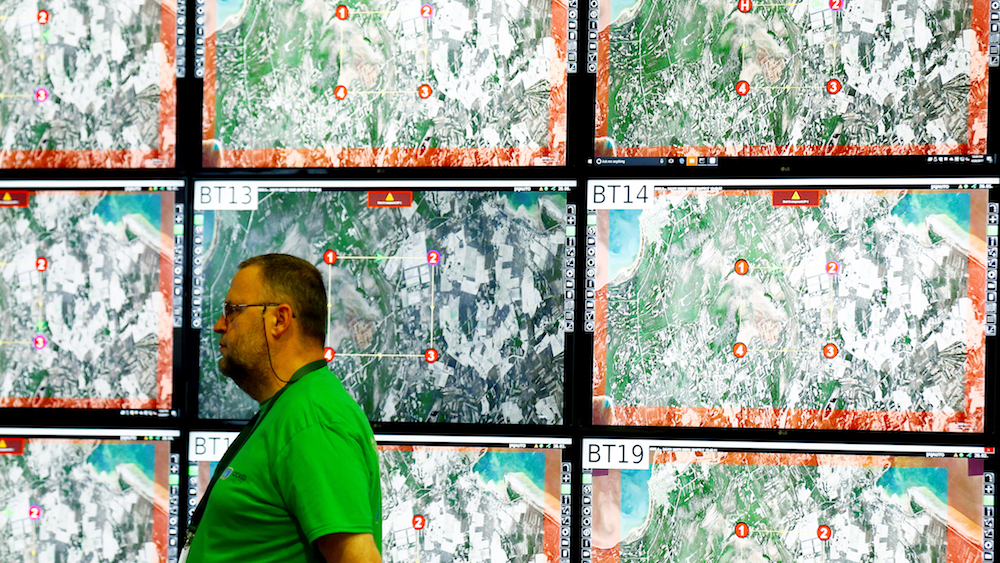

Threats can affect anyone. Only one Russian cyber operation, APT28 or “Fancy Bear,” has attacked servers of ministries, political parties, and candidates in the US, Germany, the Netherlands Sweden, Ukraine, Italy, and France and indeed even the servers of the International Association of Athletics Federations responsible for anti-doping monitoring. Military communications have also been targeted. Yet APT28 is but one of numerous groups from Russia alone. Nor is Russia the only authoritarian government seeking to increase its advantage through cyber operations. It is also clear that Iran has carried out its own offensive cyber operations. Chinese, primarily groups affiliated with the People’s Liberation Army, have targeted militaries as well as intellectual property in companies the world over.

In other words, the digital age also has ushered in an era of new security threats, perhaps imaginable but not seen until the past decade. Governments, meanwhile, have been slow to respond; multilateral organizations such as NATO and the EU have been slower. Meanwhile international organizations such as the UN have failed even to broker a treaty arrangement to prevent the use of digital weapons.

From Blocking to Hacking

Virtually every history of what is now known as “cyber war” or “cyber warfare” begins with an account of an attack on Estonia ten years ago. In 2007, the country’s governmental, banking, and news media servers were paralyzed with “distributed denial-of-service” or DDOS attacks. People’s access to virtually all major online and digitally-based services was blocked.

Cyber attacks have a far longer history of course, but until then, they were generally carried out for espionage, not to create damage to adversaries or make a political point. This case was different: it was overt and public. It was digital warfare, described by the theoretician of war, Carl Paul von Clausewitz, as “the continuation of policy by other means,” meant as punishment for the Estonian government’s decision to move a Soviet-era statue from the center of the capital.

Since 2007, overt cyber warfare and the continuation of policy by other means has proliferated and in ever more virulent form: attacks blanking out regions preceding bombing in conflict zones with DDOS attacks (Georgia, 2008); crashing electrical grids (Ukraine 2016, 2017); private companies (Sony 2015); hacking into parliaments (the Bundestag 2015 and 2106); political think tanks and parties before major elections (the Democratic and Republican National Committees 2015-16), presidential campaigns (Hillary Clinton 2016, Emmanuel Macron, 2017), government ministries (Dutch ministries, Italy’s Foreign office 2016-17, the U.S. Departments of State and Defense).

In one especially egregious case, records of 23 million employees of the US Federal government were stolen in what is known as the “Office of Personnel Management hack.” Recent testimony and leaks in the US report attempts by a foreign power to delete or alter voter data in 21 (or possibly 39 states) before the US presidential elections. These represent merely the attacks admitted to by the victims, not those unreported.

Shutting Down A Country

A decade ago, the idea of a major cyber attack was strictly hypothetical. Indeed NATO was originally skeptical about the attack on Estonia in 2007. Since the recognition of politically motivated DDOS attacks and their paralyzing impact, the focus of cyber security has shifted to more elaborate possibilities: the use of malware to shut down or blow up critical infrastructure, including electricity and communication networks, water supplies, and even traffic light systems in major cities. This goes beyond DDOS and requires “hacking,” as we know the term―breaking into servers or a computer system, not merely blocking access as in DDOS. Indeed the vulnerability of critical infrastructure became a primary concern of governments and the private sector.

These kinds of cyber attacks could mean shutting down a country, or its military, rendering it unable to oppose a conventional attack. In 2010 the Stuxnet worm, which spun Iranian plutonium-enriching centrifuges out of control, warned us of the power of cyber to do serious damage to physical systems. Leon Panetta, US Secretary of Defense from 2011 to 2013, warned in 2012 of the potential of a “cyber Pearl Harbor.” Subsequent events such as the shutting down of a Ukrainian power plant in 2016 and again this year through cyber operations showed that such concerns were hardly unwarranted.

At the same time it is worth noting that one can do considerable damage to national security and the private sector without disabling infrastructure; the hack of Sony and of the Office of Personnel Management in which the records of up to 23 million past and present federal employees are good examples of an extremely dangerous breach that endangers a country’s national security or its commerce.

From these examples, we can see that “cyber attacks” as a term is a catch-all, spanning a range of activities from attacks that can destroy a nation’s critical infrastructure on the extreme side to subtler attacks: hacking politicians, leaking compromising information, and jeopardizing election integrity.

Slow Responses

Recognition of threats in the digital world has been slow in coming, although the US and others foresaw potential threats as far back as the early 1990s. In security policy circles, it was only in 2011 that the Munich Security Conference, the West’s premier forum of security policy makers, held its first panel on cyber security.

All of these concerns have fallen under the broad rubric of symmetrical warfare. Whatever they did to you, once you figured out who “they” were, you could do back to them. Cyber attacks were all in the realm of traditional warfare but in a new domain. The US in 2010 declared cyber the fifth domain of warfare, after land, sea, air, and space. Moreover, the US Department of Defense has explicitly said that a cyber attack need not be met in the cyber domain; a kinetic response to a digital one is possible.

While NATO has acknowledged the potential threats of cyber and propaganda, it has done little operationally. NATO did set up a Center of Excellence in Cyber Security in Tallinn, Estonia, and later a similar Center for Strategic Communication in Riga, Latvia. Yet even within the alliance, there has been little cooperation.

Elections Under Attack

It has been only a year since a broader consensus has emerged among intelligence agencies and security policy experts that electoral processes themselves have come under attack. Manipulations have included “doxing” or publishing materials obtained through hacking as seen in the case of Hillary Clinton and Emmanuel Macron. Such tactics have been bolstered by manufacturing fake news on an industrial scale and propagating these through “bots” or robot accounts on social media. Gaining currency, these can be further propagated by real users. One study showed that in the three months leading up to the US election, some 8.7 million fake news stories were called up by users on Facebook but only 7.3 million genuine stories. More worrisome is the prospect of manipulations through hacking into unsecured voting machines and by altering or deleting voter data, as both the Department of Homeland Defense and a leaked NSA memo have averred.

Indeed, the propagation of fake news stories need not be tied to elections and no longer is. Instead they can simply be used in an attempt to sway public opinion. The #Syriahoax hashtag, alleging Syria’s use of chemical weapons in Spring 2017 was a Western hoax, spread virally on Twitter via bots. Fake news regarding NATO troop assignments in Eastern Europe have become commonplace. In the French election campaign in Spring 2017, bots and fake news accounts spread lies and scurrilous “facts” about one candidate, Emmanuel Macron, while leaving his primary opponent, Marine Le Pen, untouched.

A New Threat Landscape

As the past several years in this new digital age have shown, the threat landscape facing democracies has dramatically changed, ranging from traditional threats such as destruction or incapacitation of critical infrastructure to what may be termed soft threats, the manipulation of electoral democracy and public opinion. Two fundamental differences to pre-digital threats emerge:

First, geography or physical distance, a key determinant of security since the beginning of conflict, has become irrelevant. For as long as people have been thinking, proximity to threats or hostile actors was a primary motivator in security policy. NATO is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization for a reason: it is a defense organization of liberal democracies in a geographical space, constrained inter alia by tank logistics, bomber ranges, the placement of troops.

Countries traditionally have invaded or been attacked by neighbors, not by adversaries from far away. Indeed, until the age of intercontinental ballistic missiles, distance from threats was the greatest source of security and proximity the greatest vulnerability.

This is no longer true. Digital threats do not recognize distance. One is just as vulnerable half the globe away as from next door to an adversary. This is why, in the digital age, the earlier basis of alliances, be they NATO or Sparta’s Peloponnesian League, weakens or even disappears. Everyone is equally vulnerable to attack, regardless of borders or of physical distance. Cyber is a tool that can be used anywhere.

Asymmetric Attacks

Secondly, in the digital era, liberal democracies are far more vulnerable to asymmetric attacks from autocratic states than before. Propaganda, fake news, disinformation are all as old as the Trojan Horse, yet most of what was considered disinformation as late as the 20th Century had little effect. In the pre-digital age, disinformation could not easily be propagated. Fake news could not swamp and overwhelm the news media. Election rolls could not be manipulated on a massive scale and across many election districts.

Moreover, only liberal democracies are fundamentally vulnerable to attacks and manipulations of the electoral process. Authoritarian governments need not fear external manipulations of electoral processes as these are manipulated by those in power anyway. While it would be difficult to imagine a liberal democracy employing the same methods against Russia as the Russians used in the US and French presidential elections, attempting to do so simply would have no effect. To have an effect, one needs free and fair elections to affect.

From a security policy perspective, however, the possibilities of using digital manipulations can be quite attractive to an adversary. Why bother with military interventions or attacks (even digital attacks for that matter), if it suffices to use digital means to get a candidate or even a political party into office that will do your bidding or at least follow a policy line favorable to you? Certainly a Le Pen in France or the defeat of Angela Merkel in the 2017 German elections would have done more to disrupt European policy toward Russia than any kind of military action.

An Alliance of Democracies

In light of these developments in this age of “cyber,” democracies need to think beyond the hitherto geographical bounds of security. We need to rethink our security. In addition to those already in existence, we need a new form of defense organization, a non-geographical but strictly criteria-based organization to defend democracies―countries that genuinely are democracies as defined by free and fair elections, the rule of law, and the guarantee of fundamental rights and freedoms.

This idea is not new, yet proposals predating the digital era were guided more by a philosophical approach than hard security concerns. In different contexts, both Madeleine Albright and John McCain at the turn of the century proposed the creation of a community or league of democracies. Neither proposal went far at the time. The threats to democracies then, however, were not of the type described here; neither proposal was based on security concerns. Today, every liberal democracy is potentially vulnerable.

Could such an organization do the job to face this new threat? I propose that we consider a cyber defense and security pact for the genuine democracies of the world. After all, Australia, Japan, Uruguay, and Chile, all rated as free democracies by Freedom House, are just as vulnerable as NATO allies such as the United States, Germany, or my own country.

The prospects for safeguarding democracies in the digital era through such a pact are probably better now than even a year ago. Nonetheless, until this is taken up by the governments of major countries, both in NATO and outside the Alliance, liberal democracies will remain vulnerable to the new threats of the 21st century.