Tariffs, investments, infrastructure projects: the instruments of global power rivalry have changed. To assert themselves, Germany and Europe need to learn the rules of geo-economics.

We live in troubled times. Compared to the rather static geopolitics of the Cold War, today’s geo-economic confrontation between the United States, China and Europe is a far more dynamic phenomenon. What is at stake is securing influence outside of one’s own territory by using geo-economic instruments to reinforce one’s own power position. To this end, governments are attempting to control data streams, financial and energy flows, and trade in industrial goods and other technologies. Asymmetries in the international system are increasing. To maintain or to regain the capacity to act, Germany and Europe must engage in comprehensive strategic rethinking.

Change in Four Dimensions

Economic power has always been a decisive element in the international power system. Economic strength, combined with state monetary policy, represents the material basis on which to develop military capacities. At present, however, the relation between economic strength, state power and influence in the global system is being transformed along at least four dimensions.

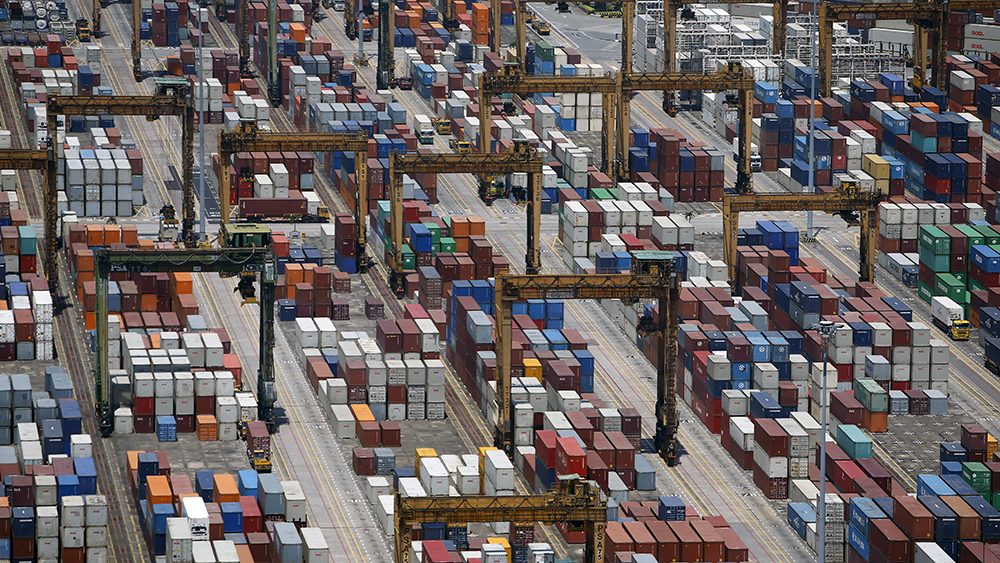

First, reciprocal dependencies—“interdependencies” —were long regarded as a stabilizing factor within the international system. Now, however, they are seen as contributing to growing uncertainty. Entanglements of trade and investment, along with ever longer supply and value chains, have considerably increased the vulnerability of many states, as well as their susceptibility to blackmail in foreign economic activities. The trend has affected weaker developing markets but also highly-developed open economies.

Second, we can observe increasing shifts in power and greater asymmetries in the international economic and financial system. This is partly driven by the return of protectionism, but the systemic conflict between the Western world and authoritarian regimes also plays a role. Another factor is the extremely heterogeneous adoption of digitalization and technological revolutions across different regions and countries: this has also fueled shifts and imbalances in economic power.

A Tool of Political Strategy

Competition to control crucial new technologies—artificial intelligence, cloud computing, quantum internet, 5G—has long been under way. Strength in innovation and technological advantage are directly relevant to security questions. Even in the energy sector, technical know-how and market leadership have a strongly political component, as well as an economic one: this is particularly the case with low-carbon technologies. Battery manufacturing and intelligent electricity networks are also good cases in point.

Third, the interdependence of economic, technological and security dimensions now determines states’ scope for action in traditional foreign policy areas and in foreign economic policy. Take the global extension of supply chains and systems of value-creation. These originally received political support, since they were regarded as a development opportunity for countries with low price levels. If components were produced in low-cost locations, or so went the idea, it was certain to benefit the manufacturing companies, the countries where production was located, and consumers in importing countries.

Fourth, inter-state conflicts are less and less a question of military action. This is primarily due to decreasing social acceptance, above all in Western societies, of traditional patterns of military conflict. The shift means that events like Russia’s violent takeover of the Crimea or the war in Syria are now the exception and not the rule. By contrast, we are seeing a sharp increase in countries’ deployment of economic and financial instruments to strengthen their power base, including outside their own territory.

The overall picture changes, however, when foreign direct investment increasingly becomes a tool of political strategy. This could lead to a debate in which implications for security policy overshadow questions of the social impact of globalization.

Parmesan and Irish Butter

A striking example of a simultaneous pursuit of economic and foreign policy interests is US foreign policy under president Donald Trump. The revised US National Security Strategy, published in 2017, equates economic security with national security, and makes the former an explicit element of foreign policy. This has formed the basis for legislation limiting foreign direct investment, like the 2018 Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act. Takeovers of American companies can now be selectively prevented on national security grounds, as in March 2018, when the US government blocked an attempted takeover of semi-conductor maker Qualcomm by a Singaporean firm.

To correct its vast trade deficits, the US has imposed tariffs on imported goods. Restricting flows of imports is intended to force compliance on the part of the foreign country in question. This is why the Trump administration has gradually racked up tariffs on Chinese goods, now totaling almost $550 billion, affecting a large proportion of all US imports from China. Against the EU, the US government imposed special import duties on steel and aluminum. Since October, new US tariffs have also hit a further range of European products, including German and French wine, parmesan cheese from Italy, Spanish olive oil, and Irish butter.

These sort of trade disputes can quickly have an effect on other economic flows, including relations between currencies. In response to punitive US tariffs, China is allowing the renminbi to weaken against the dollar. This aims to negate, or at least minimize, the effects of the new US tariff policy. As a result, the euro has considerably strengthened against the renminbi since April 2019, a trend which already has a negative effect on exports to China from eurozone countries, above all Germany.

China’s Power over States and Companies

China is also pursuing another model of geo-economic power projection. Its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) creates economic dependency that can then be turned to political purposes. The means China uses to this end are many and various: investment, agreements on raw materials and trade, energy, and infrastructure projects in Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The strategy is already working: in the UN Security Council in June 2017, Greece blocked an EU motion condemning human rights abuses in China. The previous year, Cosco, a semi-state Chinese shipping firm, had taken a majority holding in the important Greek port of Piraeus.

And there is another emerging theme for German firms to come to grips with. China not only tightly controls and spies on its own society and economy, its social credit systems and lack of data protection are forcing foreign companies to adhere to standards at odds with Western ideas of good governance and data protection.

Of course, the US and China are not the only powers using economic means to achieve political goals. Russia, for example, makes very precise use of its energy resources and infrastructure to stabilize its own political alliances and to drive wedges into other groupings. The Nord Stream 2 project is one prominent instance. The undersea gas pipeline between Russia and Germany, now at an advanced stage of development, has given rise to substantial tensions within the EU and NATO. Germany insists on its sovereign right in economic policy, emphasizing the importance of good relations with Russia. Berlin’s allies, however, continue to warn of probable German overdependence on Russian natural gas, while also criticizing how Nord Stream 2 routes gas supplies around Ukraine, depriving that country of its most important bargaining chip.

Globalizing the Power Struggle

This is a clear example of how the use of geo-economic instruments can make it difficult for Western countries to support reform processes in non-democratic or non-market-oriented states. Other examples include the founding of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, largely at the behest of China, and the creation of the New Development Bank, established by the BRICS states. Both banks were created by non-Western states as counterweights to the still-dominant Bretton Woods system. Since their credit-granting decisions are no longer subject to the conditions imposed by the West, the new supranational banks undermine the norms and standards established under the old financial order.

In addition, Brazil and South Africa are using state-owned banks and companies to develop asymmetrical relations with neighboring countries. In the Middle East, oil-rich states like Qatar and Saudi Arabia use direct financial transfers to expand their regional influence.

For decades, economic relations underwent steadily intensifying globalization. However, today it is possible to discern new and contrary trends. If great powers like China and the United States weaponize economic instruments such as tariffs, investments, sanctions, currency manipulation, and energy and data flows, there will be far-reaching consequences for the international economic system. The same is true of new control mechanisms like the screening of foreign direct investment, the partial unbundling of global supply and production chains, and new interventionist state industrial strategies, functioning on both regional and national scales.

This change is all taking place in a world economy currently experiencing weak growth, with central banks playing an ever larger role, and with debt continuing to rise. All of these developments create increasing interdependency, and also a larger number of potential targets. Geo-economic instruments are deployed in this way to bolster states’ power positions, in turn changing the basic framework of both the world and regional economies. These changes demand a substantial rethinking of states’ scope for action and the effectiveness of classical foreign and security policy.

Open and Vulnerable

Of all countries, Germany is particularly badly hit by these trends. According to the Federal Economics Ministry, the German economy has an openness index of 87.2 percent, making it the most open of all the G7 states. Around 28 percent of German jobs are directly or indirectly dependent on exports. For manufacturing industry, the figure is as high as 56 percent. Moreover, in 2017 German direct foreign investment reached a new high, at €1167 billion, with the United States its largest recipient.

In the other direction, direct foreign investment into Germany also hit a new record that year, totaling €741 billion. In this new geo-economic context, the openness which once served as Germany’s growth guarantee and the basis of its prosperity now puts the country in a particularly vulnerable situation. Moreover, this fact now sets new limits on its foreign policy options.

In 2018, Germany’s most important export partners were the United States, France, China, the Netherlands and the UK. Its most significant import partners were China, the Netherlands, France, the United States and Italy. This constellation demonstrates the difficulty confronting Germany in any escalating Chinese-American rivalry. China is a key guarantor of Germany’s economic model, but despite severe differences of opinion between Berlin and the current US administration, close trans-Atlantic relations remain crucial for Germany, in security cooperation, economic and financial relations, and in the confrontation between democratic and autocratic systems.

In other words, the political and economic aspects of geo-economic “statecraft” have to be considered alongside strategic factors. Germany’s “National Industrial Strategy 2030,” recently unveiled by the Federal Economics Minister, is a step in this direction. But the ensuing debate has revealed deep-seated instinctive reactions, with divisions between supporters and opponents of state economic aid.

The discussion about Huawei’s access to the German 5G market suggests that the intersection between economic and security policies and the debate on fundamental values has seen only limited progress, doing little to reconcile short-term economic considerations with long-term strategic questions. In addition, the significance of geo-economics is still not widely appreciated in the German public sphere. According to a Forsa survey in April 2019, 60 percent of Germans are opposed to using the country’s economic power to achieve foreign policy goals.

Making Europe Competitive

In order to successfully assert itself within the new framework of geo-economic competition, Germany must contribute towards making Europe more capable of concerted action. The new European Commission has taken the first steps in this direction, by giving responsibility for a host of central geo-economic portfolios – economy, trade, the EU’s internal market, climate, competition and digitalization, as well as foreign relations – to a new set of Commission vice-presidents. The guidelines for the new Commissioners envisage Europe exerting greater sovereignty with regard to these issues.

However, concretely implementing this new policy, while also cooperating with member state governments, will present a serious challenge. As a prerequisite for any stronger stance toward the rest of the world, the EU and the eurozone must consolidate their internal relations and strengthen their own competitiveness. Thus, for example, to ensure that the euro can play a stronger international role as an investment and trade currency, EU countries must deepen the banking union, move toward a capital market union, and create a shared safe European financial asset.

To reduce dependency on technology from non-EU states, Europeans must improve overall conditions to encourage greater competitive capacity in high-tech fields. Europe must develop its own technological strengths, a prerequisite if the EU wants to establish worldwide norms in future technologies. Achieving this will require investment in research and development, using funds both from the EU itself and from the European Investment Bank.

Some welcome initiatives are already in their early stages, for example, the development of a European data cloud and the establishment of an overarching authority on security-critical technology infrastructure, analogous to the European Medicines Agency. The European Battery Alliance, established in 2017, brings together stakeholders from every part of the battery value-creation chain, and its voice will be listened to in negotiations on next Multiannual Financial Framework.

Two Trump Cards

Attention must be paid to protective measures as well as increasing competitiveness. Protection here could, for example, include more robust screening of foreign direct investment and skepticism when foreign state-controlled investors seek to acquire a stake in key German or European companies. In order to defend against secondary sanctions, like those imposed by the United States in relation to Iran, the European Council on Foreign Relations has suggested an EU-specific agency which could implement counter-measures to protect European industry.

The shaping of economic relations with important players in the new geo-economic world goes far beyond implementing shared trade policies. The European Union needs a clear strategy on which relationships should be cultivated in trade, investment, development, energy, climate, and security: specifically, with whom should it have close partnerships, with whom competitive relations and with whom good neighborly prosperity? To determine this, security interests and economic interests must be considered at the same time.

In this context, the EU can rely on two trump cards. First, the euro, which in spite of all its crises has never seriously had its value as a currency put into doubt. Second, the EU’s internal market, which can easily keep pace with the United States and China. Meanwhile, the current challenge for the EU is to activate the effectiveness of its market power, along with the political and military strength of the Union and its member states, while strategically protecting and developing its own geo-economic advantages.