In January, the leader of the Social Democrats stood aside to make way for an outsider to challenge Chancellor Angela Merkel in September. Four weeks on, the former president of the EU parliament seems to have changed Germany‘s whole political scene. Is he a winner?

What had seemed certain is suddenly thrown wide open. For the first time since 2006, the SPD has pulled ahead of the Christian Democrats in the polls, threatening Angela Merkel’s reign. Recent poll figures indicate that the Social Democrats have risen to some 30 percent – success the party leadership could not have dreamed of at the time of the switch from the deeply unpopular Sigmar Gabriel to the great unknown that is Martin Schulz.

Headlines like “Schulz is breathing down Merkel’s neck” are setting Social Democratic hearts aflutter. At the SPD-led ministries in Berlin, euphoria has taken hold as the Social Democrats rediscover their own audacity of hope, hope that has been absent since Gerhard Schröder was voted out of office in 2005. Internet memes, Facebook pages, and the whole paraphernalia of modern electioneering have sprung up overnight. It is becoming conceivable that “Mutti” Merkel, the seemingly eternal chancellor, could actually be beaten.

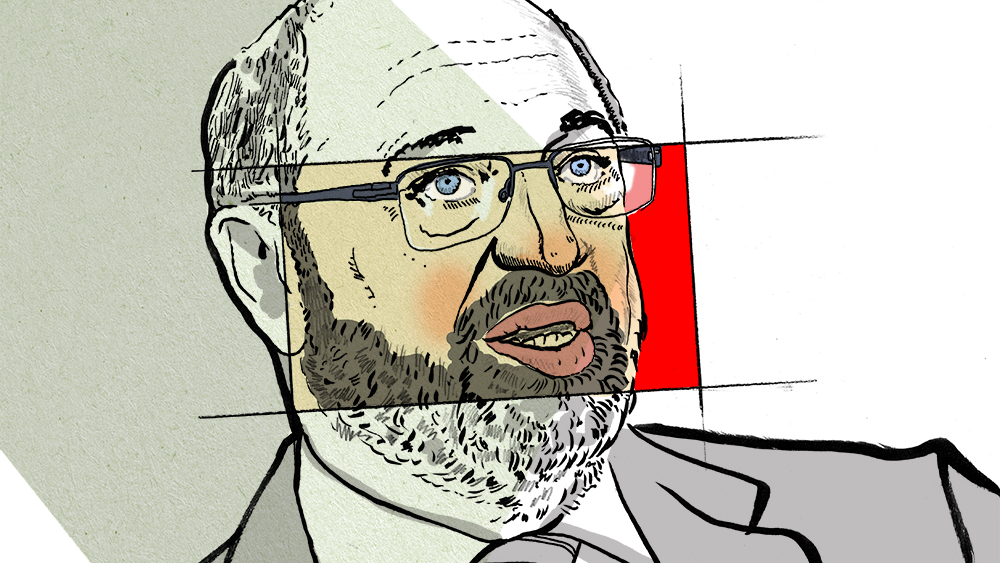

Meanwhile, Schulz – a stocky, bearded man with unfashionable glasses – has turned into an SPD superhero. Never mind that he is the unlikeliest candidate for such teen idol-like worship, and that he arrived in their midst largely unknown: He has cobbled together the most picture-perfect Social Democrat life story. That is something the party – suffering from an abundance of functionaries and policy wonks indistinguishable from those of their competitors – had not been able to come up with for years.

Small-town Boy Made Good

The special appeal of Martin Schulz lies in part in his background. He is a remnant of the SPD of yore, when former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and former party chairman Franz Müntefering represented the Social Democrats. They were men who had risen up from the working class, who had to struggle for success and stood for the street credibility of Social Democrats. When they talked about beer, football, and low wages, their voting public felt understood. The model of a politician shaped by post-war hardship had been lost for years.

But Martin Schulz has brought it back – at a time when, paradoxically enough, the traditional working-class voter has all but disappeared in Germany. Opinion polls show that he is attracting the young vote as well as previous non-voters in particular, and quite a few from Germany’s smaller parties. The poll numbers for the Greens and The Left Party have weakened recently, as has support for Germany’s right-wing populist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD).

He was born in the small town of Würselen, nestled deep in the west, where Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands meet. His father was a policeman, and money was tight at home. In his teenage years, the young Martin set out to derail his life spectacularly, neglecting school and concentrating on a career as a football player. Though he had some early success, Schulz fell apart when an injury ended his prospects. He left high school without any higher qualification and started drinking. “For some years, I drank everything I could get hold of,” Schulz admitted in an interview with the magazine Bunte three years ago.

And that is part of his special attraction: He has never tried to hide the struggles he endured in his childhood, nor has he concealed his lack of a university education. Instead, he shifts the focus to his comeback story and his iron will. Schulz admits he was even ready to end his life at the age of 24. But friends in his hometown steered him into bookselling; he finished an apprenticeship and took over one of the local bookstores.

At the same time, he became more active in the local SPD youth organization. In 1987 he was elected mayor of Würselen, a post he held for ten years. In 1994 he also became a member of the European Parliament, at that point a rather unattractive political career. There began the meteoric rise of Martin Schulz: From member of the board of Germany’s SPD to leader of the parliamentary group in the European Parliament, president of the EP between 2012 and 2017, and now candidate for German chancellor.

Few have entered this race with less experience at the domestic front. Schulz has led a town of 40,000 people and headed the EP. So why don’t voters seem to be all that bothered by this lack of political know-how? Part of the answer lies in his very public persona fighting for the future of Europe.

The Model European

In his last speech in the European Parliament in December 2016, Martin Schulz spoke of “humility” in thanking lawmakers there for their cooperation. It was an unusual sentiment coming from a man whose time in office was defined by a healthy dose of self-confidence, frank statements, and plenty of personal presence on the stage. “My aim in office is to make the European Parliament more visible and for it to be heard,” Schulz had said when taking office in 2012. It is fair to say that he almost single-handedly put the European Parliament on the map in Europe, and himself with it (or maybe it was vice versa). His work for the greater good of Europe earned him the 2015 Charlemagne Prize, the highest honor the EU has to award.

His main assets are his fearlessness before power and his gift for straight talk. When attacked by right-wing populists, Martin Schulz fought fire with fire. Back in 2003 he needled Silvio Berlusconi so much that the populist Italian prime minister said he would recommend him for the role of “kapo” in a movie about the Nazi concentration camps. During his farewell appearance Schulz shot out at Nigel Farage, foremost enemy of the EU and its institutions: “Your attacks are the pride of each European democrat.”

Schulz refused to mince his words, whether in a meeting with Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan or in an interview after Donald Trump’s inauguration, describing the new US president’s “Muslim ban” and refusal to accept refugees as “outrageous and dangerous.” He even forced European heads of government to accept his presence at the start of their otherwise top-secret council meetings.

Behind the scenes, he was a master at pulling strings and wrangling deals. EU commission president Jean-Claude Juncker, his competitor in the last European elections, became Schulz’s close friend and political partner; the two even helped form a grand coalition of European Christian Democrats and Social Democrats that functioned seamlessly. There were complaints that the two parties were far too close, but they delivered results and governed smoothly.

Next Stop German Chancellor?

Schulz is undoubtedly a seasoned politician with deep international experience. What he lacks, however, is the intimate knowledge of domestic politics that one would expect for Germany’s top job. In his first public appearances, he has steered the ship of his party markedly to the left, putting social justice at the core of his campaign.

He has already talked about rolling back some parts of the Agenda 2010, the SPD-led reforms that overhauled Germany’s labor market and, some believe, triggered years of steady growth and success. That puts him at direct loggerheads with Angela Merkel, while electrifying the more left-leaning SPD base.

Schulz has a personal talent for campaigning, and Germany is set for a heated battle over the next few months. He will have no trouble mobilizing voters in marketplaces and at sausage stalls across the country. He is still the scrappy fighter today that he was forty years ago on the football pitch, and voters seem find him credible and relatable.

But will Martin Schulz actually have what it takes to beat Angela Merkel? She is not only considered the queen of Europe, but post-Trump she has even been billed the new defender of liberal democracy. The chancellor has the standing, the respect, and the unparalleled experience in Europe and on the international stage – and that might just make her irreplaceable. Merkel is the safest possible pair of hands in very stormy times.

For many Germans, it would be a leap of faith to turn their back on the trusted chancellor and opt for the unproven newcomer, but Merkel has also been facing her greatest battle in her eleven years in office, particularly with the refugee crisis. It is early days yet, and six months are a long time in politics. Developments in the United States, among others, will determine whether the German public will really be in the mood for change come September.