The Kremlin’s efforts to influence the 2016 election in the United States are well known – even now, a special prosecutor is investigating Russia’s ties to the Trump campaign. Less well reported are Russia’s social media campaigns in Germany ahead of last month’s vote, which met with more mixed success.

Until the last moment of the German election that took place on September 24, large-scale, overt interference by the Kremlin was considered a real possibility. However, in the end Germans were spared the brazen meddling that marred elections in both the United States and France. Yet with the openly pro-Russian Alternative for Germany’s (AfD) strong showing securing its place in the Bundestag, Moscow has every reason to be satisfied with the outcome of the vote. In fact, data collected by the Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), an initiative run by the German Marshall Fund in Washington, DC, shows that Kremlin-oriented networks engaged in low-level, covert interference in Germany. Most notably, these networks actively supported AfD online by targeting the German public with the same type of disinformation they used in the United States.

Since July, ASD has been monitoring the activity of Kremlin-oriented actors on Twitter in the United States via its Hamilton 68 dashboard. Just before the German election, ASD added Artikel 38, a similar tool that monitors the activity of Kremlin-oriented Twitter accounts in Germany. The researchers at ASD trawled through thousands of followers of Russian propaganda outlets RT and Sputnik and used three metrics – influence, exposure, and in-groupness – to narrow the initial list down to 1,100 accounts, 600 in the United States and 500 in Germany, that consistently echo Moscow’s political line. The two dashboards now automatically monitor these accounts in real time and distill their content into an analyzable format.

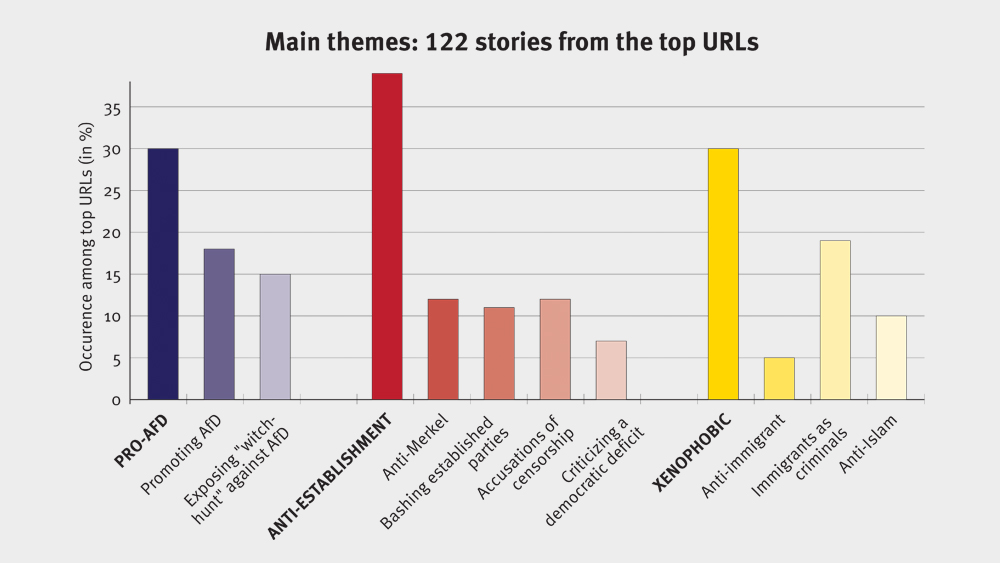

The information derived from the dashboards reveals that topics and themes promoted in both countries were very similar. In both Germany and the US, Moscow amplifies right-wing content in an attempt to exacerbate pre-existing socio-political divisions. In Germany, Artikel 38 shows that the Kremlin’s messaging follows three broad axes: xenophobic coverage of immigrants; anti-“establishment” attacks, directed at Chancellor Angela Merkel in particular; and support for AfD. Together, the themes pushed by the network target the most salient vulnerabilities of German democracy.

Xenophobic content pervades the stories tweeted by the network. A third of the 122 URLs it promoted between September 13 and September 27 directed viewers to anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic content. The tweeted stories portray immigration as a security threat and seek to stir Germans’ fears of an “Islamization” of their country. Out of 37 xenophobic stories promoted by the network, 23 portray immigrants as either criminals or terrorists. One leitmotiv concerns rapes allegedly committed by refugees. Other stories imply a link between (Muslim) immigration and terrorism. For instance, one article reported that four Syrian refugees with links to the terror group Jabhat al-Nusra were on trial for murder before a German court.

Stories that appeal to xenophobic instincts are often linked to another type of coverage that criticizes the “establishment” forces responsible for the influx of supposedly dangerous and irredeemably alien refugees. Anti-establishment content primarily focuses on Merkel and on the mainstream media outlets accused of dancing to her tune. Over the studied period, 15 URLs criticize, or even criminalize, Merkel for her way of handling Germany’s refugee crisis. These posts claim that by illegally admitting large numbers of refugees, Merkel not only sacrificed Germans’ security, but also started the steady dismantlement of German democracy and rule of law. A particular link that was among the top ten stories for three consecutive days explains why “Merkel belongs behind bars.”

Other pieces focus on “Merkel’s accomplices.” Most of them target the mainstream media, accused of censoring reports critical of Merkel and her refugee policy. Two of the most retweeted stories reported that the German public broadcaster ZDF had uninvited the relative of one of the victims of the terrorist attack that occurred in Berlin last December from a show with the chancellor. Other articles pushed by the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network in Germany focus on alleged instances of censorship and on cover-ups by state authorities, most notably by Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière and Justice Minister Heiko Maas.

By amplifying xenophobic and anti-establishment views, the network pushes the same narratives as AfD. But the network goes further than promoting ideas; it directly promotes the radical right-wing party. Since the launch of Artikel 38, AfD has dominated the hashtags, topics, and stories promoted by the dashboard. Over the period analyzed, #afd was the most tweeted hashtag, either the most or second-most important topic discussed, and the subject of a significant share of the articles pushed by the network. These articles, 36 altogether, serve two main purposes.

Firstly, they seek to create the image of a powerful AfD. Before Germans went to the polls, the network actively promoted pieces that suggested that the party’s support base might be far greater than expected. After September 24, the network was abuzz with posts that cheered the AfD’s “triumph” and gloated at the establishment’s poor assessment of the party’s real strength. Secondly, the articles aim to “expose” what the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network in Germany calls the establishment’s “witch-hunt” against AfD. According to this narrative, before the election, the other parties, mainstream media, and other “establishment” forces were accused of using censorship, fake scandals, and possibly election fraud to prevent AfD’s inevitable triumph. Having failed at their attempts, the “establishment” now tries to downplay AfD’s victory and threatens to fight, rather than engage, the party in parliament.

Honing the Message

While Moscow’s messaging is strikingly similar in Germany and in the US, the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network in Germany does have some idiosyncrasies. For instance, it plays on Germans’ strong concern for environmental issues and climate change. This is reflected in both the hashtags and topics tweeted by the network, which regularly reference issues like nuclear waste, EU regulations for the weed-killer glyphosate, and even the German recycling system. The natural disasters that recently struck the Americas were given sustained attention by the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network in Germany. On September 21, six of the 10 most trending hashtags related to hurricanes Harvey, Jose, Irma, and Maria. The network exploited these catastrophes to promote conspiracy theories, while a website that accuses US research institutes of weather manipulation and of using climate as a strategic weapon is frequently among the most-tweeted URLs of the network.

Beyond the small thematic idiosyncrasies, the dashboards also reveal significant differences between the German and American information environments. Some of these differences are intrinsic to the platform monitored, with Twitter being a much more powerful public opinion influencer in the US than in Germany. In the US, Twitter is a behemoth boasting approximately 70 million active users. In Germany, the social network never really caught on, and hovers at around a million active users. Activities on Twitter thus reach barely more than one percent of Germans directly. Of course, Twitter may still have an indirect effect: while most Germans get their news from traditional media, Twitter plays an outsized role in influencing journalists, who are on the platform and sometimes amplify or repeat its content.

Not only does the platform reach a far smaller audience, it is also used far more “passively” in Germany than in the United States. This is reflected in the dashboards. In Germany, the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network rarely posts more than 20,000 tweets a day, whereas in the United States, it rarely falls below the 20,000-tweet mark. This is further reflected in the fact that the content pushed by the networks sees a far smaller number of retweets in Germany than in the United States – a clear indicator that Germans interact less with messages posted by others. For instance, between September 25 and 27, the five most-tweeted posts were retweeted an average amount of 204 times in the United States versus an average of 39 times in Germany.

Another significant difference between each country’s Kremlin-oriented Twitter network is the number and weight of sources each one uses. In Germany, the content promoted by Moscow sympathizers emanates largely from a small number of single-authored fringe blogs. Large national or local media outlets are seldom referred to. To some extent, it seems that content promoted by Russia is restricted to a niche audience and is isolated from the broader public debate.

The situation is very different in the United States, where Russia has a much larger number of websites whose messages it can amplify. Small sites analogous to the German fringe blogs are more numerous and appear to draw from a larger pool of contributors. More importantly, the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network in the United States relies heavily on content from large outlets such as Breitbart and Fox News. These big organizations allow the Kremlin-oriented Twitter network to be far more embedded in the American public debate than in the German one.

Moscow adopts the same propaganda strategy on both sides of the Atlantic. It uses social media to bolster the political extremes, the far-right in particular, and extend the reach and toxicity of their divisive rhetoric. But analyzing the dashboard’s data suggests that the Kremlin’s online tactics might be better suited to the United States than to Germany. The Kremlin-oriented Twitter network reaches more people in the US, and the American public more readily engages with content pushed by Moscow. In addition, Russian online campaigns in the US can draw on large media outlets and get to people beyond the restricted confines of the far-right.

That’s not to say that Germany is immune to Kremlin interference. AfD has learned from, and largely adopted, the online tactics Moscow used to great effect in other Western democracies. Moreover, as a party in Parliament, AfD is now very likely to have a much-improved access to media channels that have real sway over the German public. If the far-right party maintains its openly Pro-Russian line in the coming months, Moscow will have a Trojan horse perfectly poised to take the German informational landscape by storm.