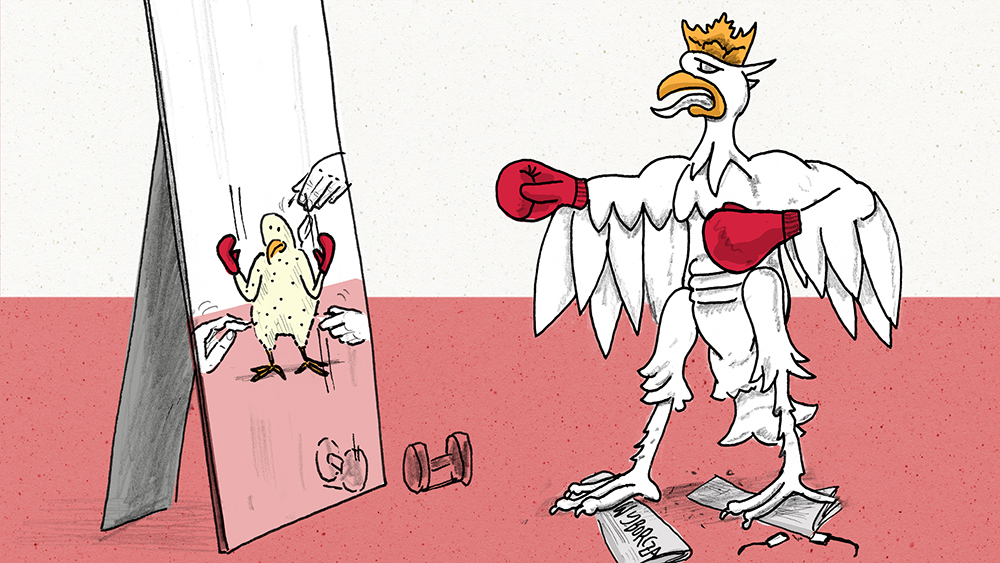

They call themselves “the unbowed” and style themselves as Poland’s principled opposition marginalized by the mainstream. In fact, they have taken over much of the country.

They inhabit the top tiers of state media. They work in editorial offices supported by state-owned firms. And they have direct access to the powerful chairman of the Polish ruling party, Jaroslaw Kaczynski. Yet in a remarkable and continuing instance of doublethink, they also portray themselves as a minority, persecuted by the mainstream and the establishment for their inconvenient truths. They call themselves niepokorni (the unbowed) – and their story says more about the agitated public debate and political atmosphere in Poland than most political analyses.

The term niepokorni has a long and honorable history. It echoes through a country where resistance to those in power plays a particularly strong role in political identity. It originates from a book published in the early 1970s – The Genealogy of the Unbowed – that inspired a whole generation of democratic opposition. It told the biographies of Polish intellectuals and politicians of the 19th and 20th centuries, people who had followed their ideals and goals without compromise, despite the resistance of the powerful and a zeitgeist that was heading in a different direction.

The new niepokorni took to the stage at the end of 2012. Following a conflict with a new publisher, a group of prominent conservative commentators from the second biggest Polish daily newspaper Rzeczpospolita walked out and started a new paper. Its first front-page headline read, “The Unbowed Are Back.”

They left amid one of the biggest media scandals in Polish history. In 2012 Rzeczpospolita published a story with the headline, “Explosives Found in the Wreck.” The author claimed that traces of explosives had been uncovered among the remains of the government plane that had crashed near Smolensk the previous year, killing 96 passengers including President Lech Kaczynski. The theory that Poland’s president had been assassinated was already cooking within the country’s right-wing circles. Now it seemed to gain traction. Yet the story itself had none. The journalist failed to produce evidence to support the claim, which the general prosecutor would later dismiss.

The publisher fired those journalists who clung, unimpressed, to the assassination theory. They later accused him of cozying up to the governing party Civic Platform, itself an archenemy of the right. It all fit perfectly into a new legend of the unbowed.

The new paper they founded was part a resurgent right-wing, conservative branch of the Polish media. Until then it had been a fairly unproductive branch, and that fact itself was incorporated into the new legend. The unbowed saw themselves as having been excluded by the dominant, left-leaning liberal media (particularly Gazeta Wyborcza) for years, if not decades. They felt humiliated and sidelined. Yet in fact, most of the media projects started by those on the right during the 1990s had simply failed, leaving the dominance of Gazeta Wyborcza unchallenged.

This boiled down to the niepokorni defining themselves as “anti-salon,” even adopting the phrase for the name of a TV show hosted by one of their most prominent members. They saw themselves as an uncompromising counterweight to the “liberal elite,” to what they portrayed as the “industry of disrespect” (to nationalist or conservative opinions), and to the “madness of political correctness.”

The “salon” they oppose is an indispensable element of the unbowed identity. They see it as an illegitimate moral authority of the Third Republic, which they say is built on the left-liberal legacy of the Solidarnosc movement and undermined by former communists. Not belonging to the salon – or even better, being excluded from it – is a source of continuing frustration. And even a complete upheaval of the political climate and the media landscape has not been enough to quench the thirst for right-wing insurrection.

Yet that is what has already taken place. The political agenda-setting power of Gazeta Wyborcza waned at least a decade ago, and the unbowed have long inhabited prominent positions in state media (the author of the “plane plot” article is now Berlin correspondent for Polish public TV station TVP). They successfully capitalized on the emotions stirred by the Smolensk tragedy to cement their place at the top. Their media networks now include the best-selling weekly paper Do Rzeczy, Gazeta Polska, Nasz Dziennik, and wSieci, as well as the internet portals polityce.pl and niezalezna.pl, the TV broadcaster Republica and also TV Trwam, which is linked to the infamous radio station Radio Maryja.

They have succeeded in turning this into political influence; no one disputes the idea that their support for Jaroslav Kaczynski’s Law and Justice Party (PiS) was of central importance to its electoral success in 2015. Since then they have completely “reconquered” public – now national – media, and enjoy a hefty income from state-owned companies. The unbowed have written a media success story the likes of which is difficult to find anywhere else. And with that, they have significantly influenced a narrative of Polish modern history that many are happy to ascribe to: a country corrupted and driven into the ground by liberals and now led by the right to recovery, success, sovereignty, and, most importantly, national dignity.

The Unbowed are today at the height of their influence – as is their hero Kaczynski. And this despite the fundamental contradiction at the heart of their legend: they portray themselves as and even believe themselves to be the informal leaders of the country, while at the same time suffering repression and defending themselves against the hated salon. The original niepokorni must be turning in their graves.